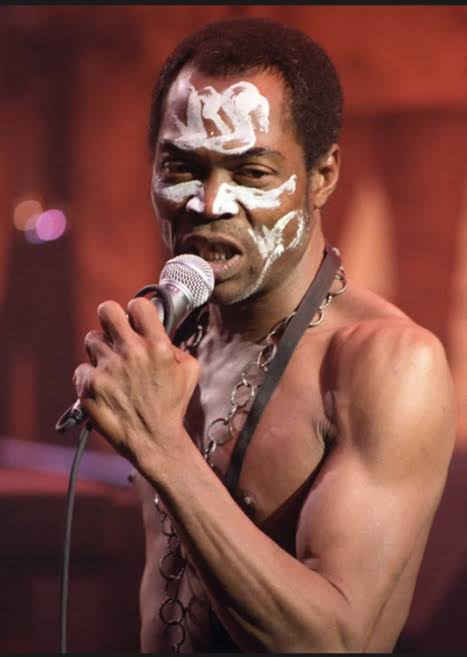

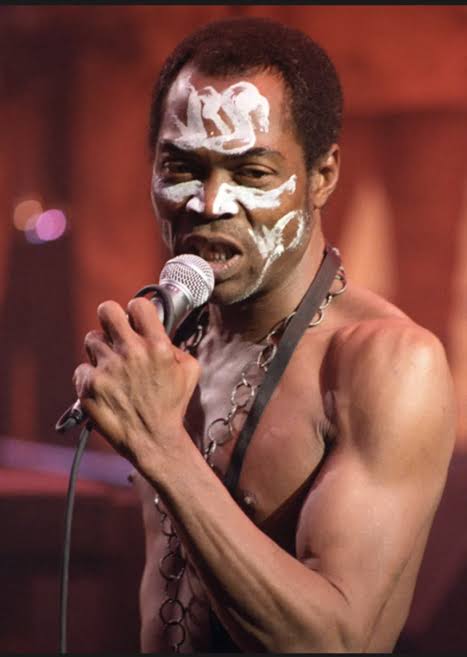

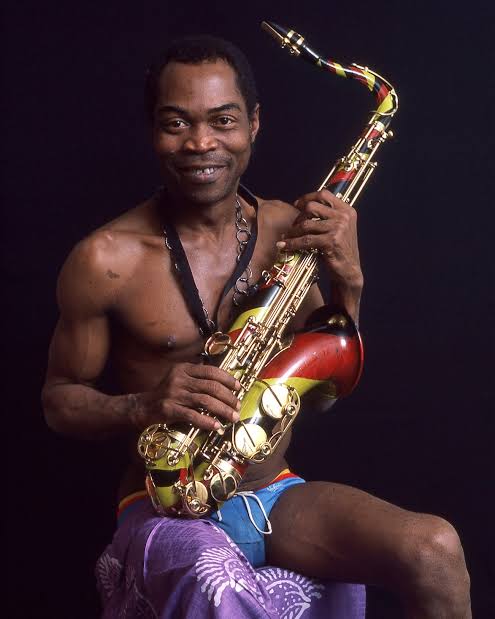

Afrobeat did not emerge in isolation; it was forged in the turbulence of postcolonial Nigeria, where music, politics, and power constantly collided. At the centre of this collision stood Fela Aníkúlápó Kuti, a bandleader whose saxophone became both an instrument of entertainment and a tool of defiance. By the mid-1970s, his music had grown into more than rhythm and dance—it had become a language of protest that unsettled Nigeria’s military rulers and electrified the streets of Lagos.

- The Fuse: How a Song Turned to a Street Fight

- The Place: Kalakuta as Music Factory, Shelter, and State of Mind

- The Night the Soldiers Came

- Saxophone as Siren: What the Music Was Doing

- Lagos on Edge: The City as Chorus

- The Coffin March and the Politics of Memory

- Why the State Feared a Bandstand

- The “Unknown Soldier” and the Known City

- Afterlives: Museum, Shrine, and the Grammar of Defiance

- The Music as Archive

- Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti: The Other Center of Gravity

- Costs, Complications, and the Human Mess

- What That Night Teaches Lagos (and Artists Everywhere)

- FINAL THOUGHTS: The Note That Keeps Ringing

Fela’s art challenged not only corruption but also the culture of unquestioned obedience. His compound, known as the Kalakuta Republic, functioned as a communal space, recording hub, and symbol of resistance. In it, he nurtured a vision of cultural independence and political critique that would eventually bring him into direct confrontation with the state.

This article explores how Fela’s music, politics, and lifestyle converged in 1970s Lagos, and how a single song became the spark for one of the most consequential episodes in Nigeria’s cultural and political history.

The Fuse: How a Song Turned to a Street Fight

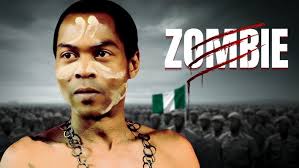

By the mid-1970s, Lagos already knew Fela’s provocations: an unrelenting nightly residency at the Shrine; records whose A-sides stretched to 12, 15, 20 minutes; and lyrics—mostly in Pidgin—that mocked corruption with a carnival barker’s bite. But “Zombie,” recorded in 1976 and released widely in 1977, changed the stakes.

Built on Tony Allen’s fractal drum grid and a brass line that advanced like a parade from hell, “Zombie” lampooned soldiers as mindless order-takers—“go and kill… go and die”—and Lagos danced the insult into ubiquity. Within weeks, the tune was being chanted at football grounds and barracks gates. The military heard it the same way the streets did: not as metaphor, but as a dare.

The daring was public—and pointed. Fela had already “seceded” in spirit. He named his commune Kalakuta Republic, ran a free clinic and a studio within its walls, and called himself a citizen of Kalakuta rather than of a Nigeria he described as militarised by colonial hangovers. The taunt of “Zombie” made the republic feel less like theatre and more like a barricade.

The Place: Kalakuta as Music Factory, Shelter, and State of Mind

Kalakuta was deceptively simple: a three-storey block at 14 Agege Motor Road in Mushin. Inside were Fela’s family, bandmates, technicians; instruments and master tapes; a small clinic; and the stubborn belief that culture could be a sovereign power.

Nights bled into mornings: rehearsal into show, show into recording, recording into argument. In that tight ecosystem, music was not product; it was infrastructure. The horn parts that Lagos danced to were hammered in rooms whose windows rattled from petrol fumes and the shouts of roadside hawkers; the politics that roared out of studio monitors were argued at kitchen tables and on the stoop.

To the military, it was a standing provocation: a “republic within a republic,” with its own passports and its own rules, anchored by the nightly spectacle at the Shrine—a spectacle that police raids, bribery demands, and court dates only seemed to amplify.

The Night the Soldiers Came

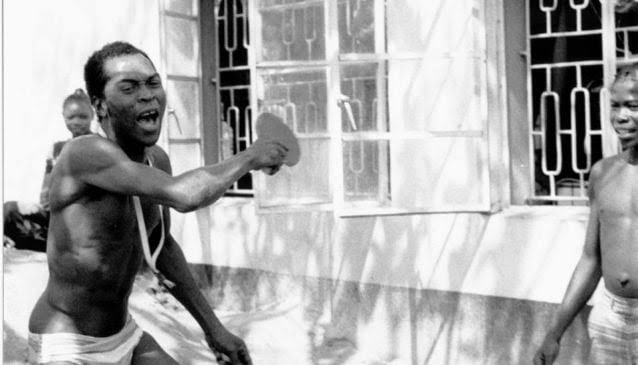

On the morning of February 18, 1977, Lagos woke to rumours that the army was moving. By noon, the rumours were fact: hundreds of soldiers—by many accounts nearing a thousand—surrounded Kalakuta, battered through its gates, and fanned out across the property.

They beat residents and musicians, torched rooms, smashed equipment, and hauled Fela into custody, bloodied and with a leg in plaster. Amid the chaos, his 77-year-old mother, the legendary activist Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, was thrown from a second-floor window. She would die the following year from injuries sustained in the attack. The building burned to a skeleton. Lagos stared. And then Lagos talked.

Contemporaneous reporting made clear just how deliberate the assault was. In a dispatch two days later, The New York Times described soldiers “burning the home of a dissident musician”—explicitly linking the raid to “Zombie” and to Fela’s constant needling of the Obasanjo military government. Nigerian and international coverage converged on the essentials: the scale of the force used, the destruction of the studio and master tapes, and the injury to Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti.

The official explanation stretched belief. A later board of inquiry blamed the arson on an “unknown soldier.” The phrase became a bitter national punchline—a euphemism that told the truth about impunity without naming a culprit. Fela would immortalise it on vinyl.

Saxophone as Siren: What the Music Was Doing

To understand why “Zombie” provoked such fury, listen not only to its words but to its arrangement. Fela’s sax is not the frenetic bebop of flight; it is a slow, jeering cantus threading a military groove and turning cadence into critique.

Tony Allen’s drums refuse the square march; guitars insist on a syncopated vamp that tugs the rhythm off any parade ground. The horns, when they stack, sound like a brass band that has switched sides. This was choreography as politics: the band drilled like soldiers to mock soldiering itself. No wonder barracks bristled.

The songs that framed the raid—“Sorrow Tears and Blood” especially—sound like affidavits. Their structures mirror testimony: long, detailed, repetitive by design, building cases out of riffs and witness lines (“Them leave sorrow, tears, and blood”).

Where a court offered “unknown soldier,” Fela offered names of injuries and the choreography of baton blows, setting them to a groove that made denial feel ridiculous. Music became record, record became record-keeping.

Lagos on Edge: The City as Chorus

Lagos did not burn in a literal city-wide conflagration that day; it burned with talk—with the kind of rumour, rage, and gallows humour that makes a megacity hum louder than its generators.

Soldiers at roadblocks suddenly found themselves the butt of a punchline they could not interrupt. Bus conductors whistled horn lines. Market women shook their heads and invoked “mama Kuti.” Even those who thought Fela’s lifestyle excessive understood that something unacceptable had been done to the city’s sense of itself when a bandstand was treated as a bunker. In the streets, the music had already won the argument: if a song could make the state this afraid, perhaps the song was right. (This interpretation is borne out by later analyses connecting the symbolic power of the “Kalakuta Inferno” to the way Lagos remembers state violence.)

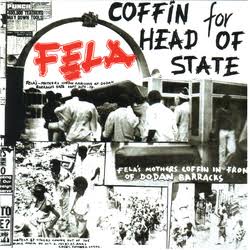

The Coffin March and the Politics of Memory

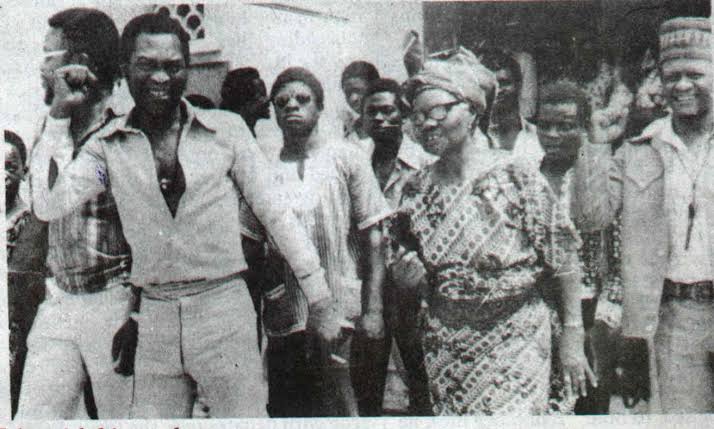

Fela’s reply was as theatrical as any single he ever cut. In a piece of political street theatre that Lagos still retells, he carried his mother’s coffin to Dodan Barracks, the seat of the military government, to lay it “at the door” of power.

The act condensed a hundred columns of argument into one image: the state’s monopoly on violence confronted by a son’s grief and a city’s gaze. The songs followed—“Coffin for Head of State” and “Unknown Soldier”—sound-tracks not only to an event but to a movement of memory in which Lagosians refused the erasure that official language attempted.

In the months after the raid, authorities closed the Shrine, and Fela decamped briefly to Ghana before returning to Lagos in 1978 to remount his nightly campaign in music form.

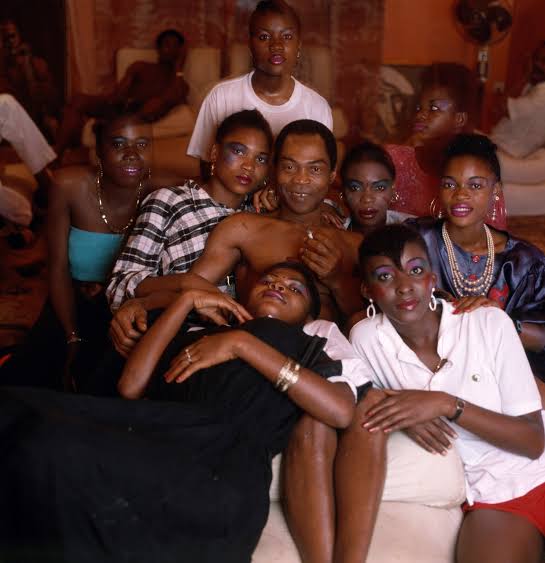

He married 27 women—his “Queens”—in a widely publicised ceremony that he framed as solidarity after the raid left dancers and singers stigmatised and unemployed.

Whatever one makes of the gender politics (and many critics have made plenty), it was consistent with his instinct to answer the logic of force with the spectacle of community.

Why the State Feared a Bandstand

Why did a band become a national security problem? Because Fela fused three things regimes struggle to answer at once:

1. A nightly public square. The Shrine was court, parliament, newsroom, and dancehall under one roof. Stories broken there—about police shakedowns, fuel scams, barracks abuses—spread faster than state messaging ever could. Raids only added to its mystique.

2. A music that made complexity danceable. Afrobeat’s long-form grooves were slow-burning arguments; they taught listeners where to place their bodies and their anger. The saxophone’s glissando could feel like a judge’s sigh, the horn stabs like exclamation points.

3. A politics with receipts. By running a clinic, employing dozens, and housing a commune, Kalakuta made governance claims—however improvised—that embarrassed officialdom. Burning the building was, in that light, less an assault on a musician than a raid on a competing idea of how to live in a city.

The “Unknown Soldier” and the Known City

The board of inquiry’s euphemism did not work on the streets. “Unknown soldier” became Lagos shorthand for the brazenness with which power absolves itself. The same phrase made its way into set-piece rants onstage, into newspaper cartoons, and into social memory.

Years later, when new episodes of state violence convulsed the country, commentators and scholars reached back to the Kalakuta Inferno as a template for how music records trauma and how cities refuse amnesia. The continuity is not accidental; Afrobeat trained a generation to hear doublespeak for what it is.

Afterlives: Museum, Shrine, and the Grammar of Defiance

Time has folded the site of the assault into memorial. In 2012, Lagos State helped transform a later Kuti home in Ikeja—the one he moved to after Kalakuta’s destruction—into the Kalakuta Museum, a preserved apartment, small gallery, and roof-bar that functions as both shrine and archive.

In the surrounding district, the New Afrika Shrine hosts nightly music, rehearsals, and the annual Felabration festival organised by Fela’s children. The city that once sanctioned a raid now sponsors stages. History is nothing if not ironic.

The family, for their part, refuses soft-focus remembrance. On anniversaries of the 1977 raid, Femi and Yeni Kuti recount the details publicly—how the building burned, how their grandmother fell—insisting that memory is not vengeance but clarity. In 2022, on the 45th anniversary, they once more demanded justice in the press and on social media.

These commemorations matter not only to the Kuti family but to Lagos’s civic health: they keep the city’s ear trained to hear the difference between official narrative and lived history.

The Music as Archive

For all the op-eds and inquiries, the most durable archive of the raid is on record. Listen again to the opening of “Sorrow Tears and Blood”: the band enters like a witness taking an oath—measured, grave, detailed.

The horns catalogue a scene; the chorus names the residue of baton and matchstick; the rhythm section refuses hysteria, choosing instead the steady pulse of recollection.

This is not protest as explosion; it is protest as minutes of a meeting, exact and unhurried, copied to reel-to-reel so it can be played back in court. The same is true of “Coffin for Head of State,” whose long vamp stretches time into contemplation until the coffin’s weight feels like it is in your own hands. These are not just songs about a night; they are technologies for remembering a night.

“Zombie,” for all its swagger, is cooler than its reputation suggests. The call-and-response is a pedagogy: the band instructs, the chorus repeats, the crowd learns. In doing so, it converts a critique into a muscle memory. To hear the song was to learn how to move against command. That is what the soldiers heard and feared. That is why they came.

Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti: The Other Center of Gravity

To understand the moral charge of the 1977 raid, you must reckon with who was injured: not only a bandleader, but the foremost women’s rights activist of her generation. Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti led market-women’s tax protests in Abeokuta in the 1940s, challenged colonial and traditional authorities alike, and built the political grammar Fela adapted for the stage.

Her fall from that second-floor window felt to many like an attack on the very memory of women’s political leadership in Nigeria. Her death in April 1978 sealed the raid’s place in national conscience.

Costs, Complications, and the Human Mess

A truthful telling should also look unflinchingly at contradictions. Fela’s life after the raid traced both a heroic arc and a complicated one. He briefly exiled himself to Ghana, then returned to Lagos to wage sonic war anew.

He married 27 women in 1978, describing the ceremony as protection for dancers stigmatised after the raid; critics read it differently, and serious debates about misogyny have shadowed the legacy ever since. But even those debates testify to the size of the footprint: few artists leave enough behind to argue over.

Musically, the costs were staggering. Master tapes burned. Instruments charred. A studio—an entire economy of making—gone. Yet out of that loss came a run of records that doubled as case files and hymns. Afrobeat, instead of retreating, expanded—into longer forms, deeper fusions, and more explicit naming of names. The soldier tried to end a style and helped cement a canon.

What That Night Teaches Lagos (and Artists Everywhere)

First, that states fear rhythm because rhythm organises bodies. The genius of Afrobeat was to make governance a matter of timekeeping, to turn citizenship into knowing where the “one” is. In a city as improvisatory as Lagos, that knowledge can travel faster than any communiqué.

Second, that memory requires craft. Without the records Fela cut, “unknown soldier” might have stood as a bureaucratic period. With them, it lives on as a punchline and a warning. Songs are not merely emotions; they are tools.

Third, that place matters. The struggle over Kalakuta was a struggle over a small piece of Lagos real estate—and over whether a city’s residents can insist on living loudly enough to be free.

Finally, that art can be both imperfect and indispensable. Fela could be maddening, excessive, contradictory. He could also be the exact instrument Lagos needed to hear itself clearly. The saxophone that mocked a junta taught a generation to dance with its chin up.

FINAL THOUGHTS: The Note That Keeps Ringing

On certain nights at the New Afrika Shrine, when the band locks a vamp and the crowd answers in Pidgin, you can hear a memory stretching across five decades. Somebody will inevitably call “Zombie!”—half joke, half invocation—and the laugh that follows is never just a laugh. It is Lagos reminding itself that it has already survived a fire meant to silence it. It is the city saying that the saxophone won.

The soldiers had boots and trucks and the power to burn a building. The band had charts and lungs and a way of making truth repeatable. History tells us which force travels farther.