In the turbulent 1940s, when British colonial power still held Nigeria in a tight grip, one man discovered that the stage could be as dangerous as the streets and as powerful as the ballot.

- Childhood of Dual Worlds: Hymns and Oriki

- The Garden of Eden: Discovery of a Stage

- The Strike and Hunger (1945): A Stage Becomes a Weapon

- Birth of the Ogunde Theatre: The First Professional Company

- Bread and Bullet (1950): Mourning the Enugu Miners

- Arrests, Bans, and Censorship

- A Style That Belonged to the People

- Independence and New Disillusionments

- Cinema and Later Years

- Legacy: The Drumbeat of Defiance

- Closing Reflection: A Curtain That Never Fell

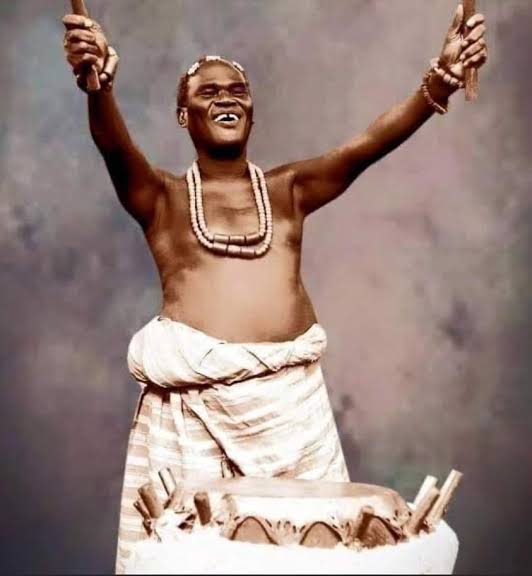

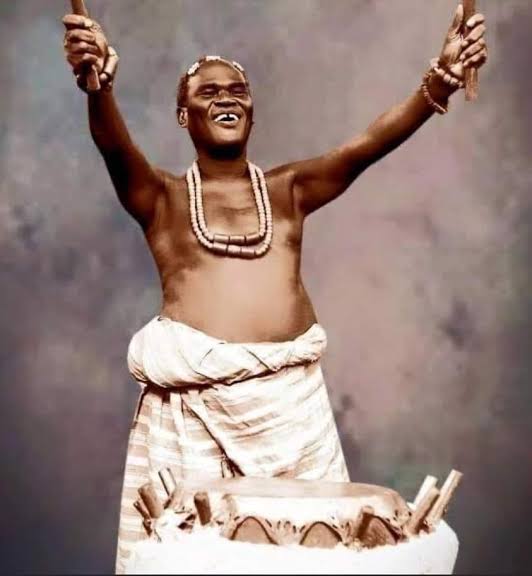

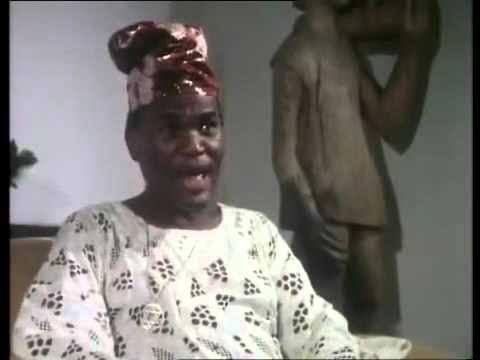

Hubert Ogunde, often called the father of modern Nigerian theatre, transformed performance into a weapon of resistance. His plays, laced with Yoruba chants, gospel hymns, biting satire, and defiant storytelling, did more than entertain — they exposed injustice, mobilized communities, and unsettled colonial authorities.

Long before Nigeria gained independence, Ogunde’s theatre became a rallying ground for national consciousness, challenging not just the British establishment but also the complacency of his own people.

This article explores how Hubert Ogunde’s groundbreaking theatre not only defied colonial rule but also laid the cultural foundation for Nigeria’s modern performing arts and nationalist movements.

Childhood of Dual Worlds: Hymns and Oriki

Hubert Ogunde was born in July 1916 in Ososa, a small town in present-day Ogun State. His lineage bridged two worlds. His father, a devout Baptist pastor, embodied the missionary presence that had reshaped Yoruba life since the nineteenth century. His mother, however, remained deeply rooted in Yoruba traditions, raising him on oriki—praise chants that celebrated ancestry and character.

Young Hubert grew up singing hymns in the church choir while also absorbing the cadence of Yoruba folklore. Sundays meant Anglican liturgy; evenings meant listening to elders recount tales of tortoise trickery, gods, and warriors around lantern light. This dual immersion would later define his genius: he could speak both the language of the colonizer’s faith and the rhythms of indigenous memory.

Before theatre consumed him, Ogunde walked other paths. He became a teacher, then briefly a colonial policeman. Both jobs exposed him to authority and its failings—the frustrations of low wages, the humiliations meted out by British superiors, the despair of ordinary Nigerians. These experiences simmered in him until they found release on stage.

The Garden of Eden: Discovery of a Stage

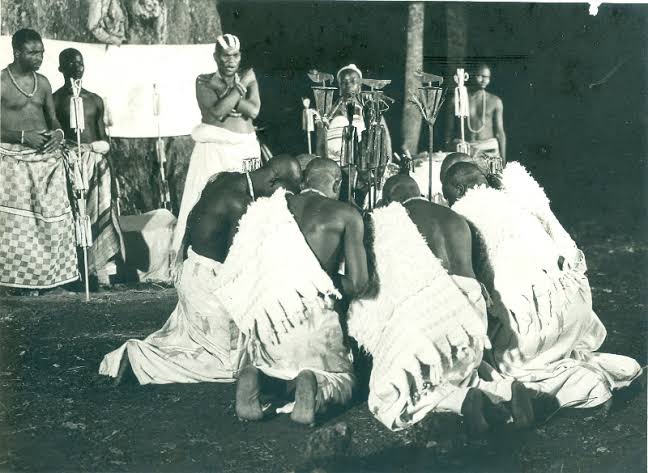

His first breakthrough came in 1944 with The Garden of Eden and the Throne of God, performed in Lagos. At first glance, it was a standard Christian morality play, dramatizing biblical events. But Ogunde gave it a distinctly Nigerian flavor. Angels moved with Yoruba dance steps; dialogue shifted into Yoruba mid-scene; drums punctuated heavenly announcements.

Audiences were stunned. Here was theatre that felt familiar, not foreign. It was biblical but also Yoruba, modern yet rooted in tradition. The colonial establishment was mildly amused, seeing it as harmless creativity.

For Ogunde, however, the play was more than entertainment: it was proof that theatre could carry serious messages—and reach the masses more viscerally than any pamphlet.

The Strike and Hunger (1945): A Stage Becomes a Weapon

By 1945, Nigeria was a tinderbox. World War II had ended, but inflation was strangling workers. Wages lagged, food prices soared, and colonial employers remained unmoved. A general strike loomed. In this climate, Ogunde unveiled The Strike and Hunger.

The play dramatized starving families, corrupt overseers, and the desperation that pushed workers toward protest. It portrayed strikers not as troublemakers—as colonial propaganda insisted—but as victims of systemic injustice.

The colonial authorities recognized the danger. Here was no abstract parable but a mirror held up to their cruelty. Police reports noted the “unruly enthusiasm” of audiences.

The play emboldened workers who would later pour into the streets during the 1945 General Strike—one of the largest labor uprisings in colonial West Africa.

Ogunde had crossed the line from entertainer to agitator. His theatre was now political theatre.

Birth of the Ogunde Theatre: The First Professional Company

In 1945, Ogunde founded the African Music Research Party, later renamed the Ogunde Theatre. It was the first fully professional theatre company in Nigeria.

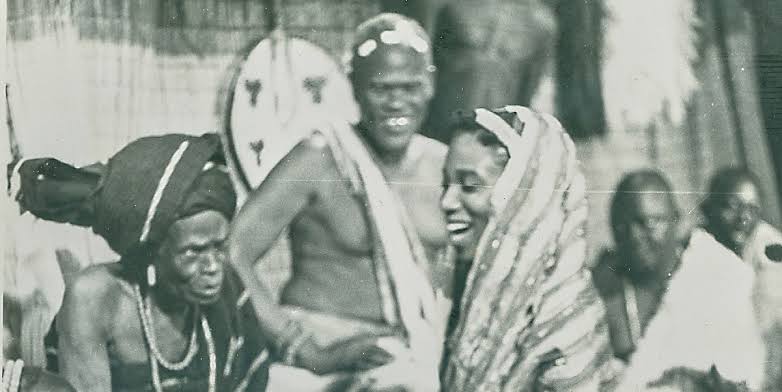

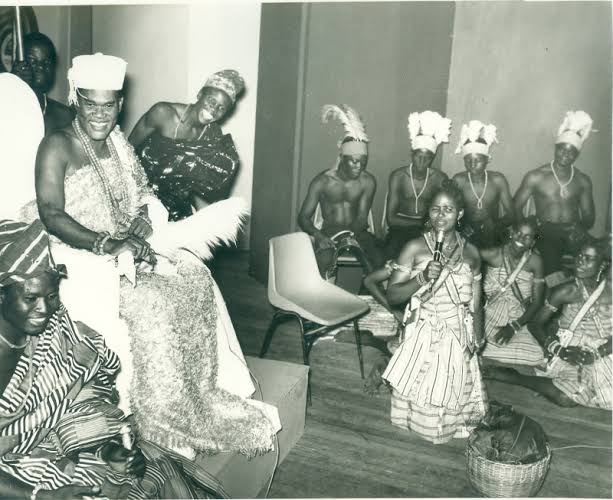

While missionary plays were amateur productions staged by students, Ogunde’s troupe was a dedicated collective. Actors, drummers, dancers, and singers rehearsed daily, lived on touring schedules, and survived on ticket sales. The troupe performed in schools, community centers, market squares, and town halls, often to thousands.

Their style was revolutionary. Yoruba chants opened scenes; comic interludes satirized authority; drums amplified political messages. Yet they also borrowed European theatrical devices: curtains, sets, lighting. This fusion made Ogunde’s theatre both traditional and modern, local and cosmopolitan.

It also made it dangerous. For the first time, theatre reached ordinary Nigerians not as religion or colonial “recreation,” but as political education.

Bread and Bullet (1950): Mourning the Enugu Miners

The next milestone came with Bread and Bullet, staged in 1950. It dramatized the tragic Enugu coal miners’ strike of 1949, where colonial police shot and killed 21 unarmed miners demanding better pay.

Ogunde staged the massacre with visceral power: actors fell to the sound of gunfire; women wailed and tore at their clothes; blood was simulated on stage. The audience erupted in grief and fury. Survivors of the massacre reportedly wept in the crowd.

The colonial government swiftly banned the play, accused Ogunde of incitement. But the ban only amplified its power. Nigerians whispered about the forbidden performance, and Ogunde’s name became synonymous with courage.

Arrests, Bans, and Censorship

From the late 1940s onward, Ogunde lived under constant colonial scrutiny. His plays were vetted, sometimes censored, and occasionally banned. In 1946, after staging Tiger’s Empire, a thinly veiled allegory of anti-colonial struggle, he was briefly arrested. Police surveillance reports described his plays as “subversive” and “calculated to stir resentment.”

But repression rarely silenced him. On the contrary, it turned him into a folk hero. Each ban confirmed what Nigerians already knew: Ogunde was speaking the truth.

A Style That Belonged to the People

What made Ogunde irresistible was his accessibility. His plays switched seamlessly between English and Yoruba. Where colonial officials insisted English was the only language of “civilized” theatre, Ogunde democratized performance. Market women, artisans, students, and elites could all follow his stories.

Theatre became not just spectacle but a communal experience. Audiences sang along, clapped, and sometimes joined in call-and-response. His plays did not “preach down” to the people—they spoke with them, in their language, with their humor, and about their struggles.

This was why colonial bans failed. Even when denied formal stages, Ogunde’s songs and lines traveled through markets and taverns. His theatre lived wherever Nigerians gathered.

Independence and New Disillusionments

When Nigeria gained independence in 1960, Ogunde stood tall as a cultural pioneer. Nationalists celebrated him as the “father of Nigerian theatre.” But Ogunde was not satisfied to bask in symbolic glory. Independence had come, but true justice had not.

In 1964, he staged Yoruba Ronu (“Think, Yoruba”), a searing critique of tribal politics tearing apart Western Nigeria. The play satirized leaders who exploited ethnic loyalties for power, warning of disaster.

The regional government of Chief Ladoke Akintola banned it almost immediately, calling it seditious. For two years, Ogunde’s theatre was shut down in the West. His resilience never wavered. He declared that theatre must serve the people, not rulers—colonial or Nigerian.

Cinema and Later Years

From the late 1960s into the 1980s, Ogunde expanded into film, producing works like Aiye (1979) and Ayanmo (1988). His films blended mysticism, Yoruba spirituality, and moral commentary, reaching wider audiences in the emerging Nollywood space.

Yet theatre remained his first love. By his death in 1990, he had written more than 40 plays, trained countless actors, and built a tradition that still echoes through Nigerian drama.

Legacy: The Drumbeat of Defiance

Hubert Ogunde’s theatre achieved what few weapons could. It gave Nigerians a mirror of themselves—not as colonial subjects, but as people with dignity, agency, and history.

He showed that theatre could be a form of resistance as potent as strikes or rallies. His plays outlived governors, outwitted censors, and inspired generations. He turned the stage into a battlefield where drums, satire, and chants carried the banner of freedom.

Even today, when Nigerian theatre wrestles with commercialization and Nollywood’s dominance, Ogunde’s legacy lingers. His work reminds us that performance can be more than spectacle—it can be struggle, memory, prophecy.

Closing Reflection: A Curtain That Never Fell

In the archives of Nigerian resistance, Hubert Ogunde’s stage deserves a central place. He was not merely a dramatist, but a cultural revolutionary who dared to turn art into politics. The colonial government tried to silence him; postcolonial leaders did the same. But his plays proved what audiences already believed: that the stage could tell truths no law could suppress.

Ogunde’s theatre defied colonial rule not by rejecting art for activism, but by fusing the two. In every drumbeat, every chant, every satirical line, he declared that Nigeria would be free.

And though the curtain has long since fallen on his earthly stage, his theatre remains alive—still speaking, still resisting, still reminding us that freedom, once imagined, can never be censored away.