Ayinla Omowura’s voice was the pulse of Abeokuta. From the dusty motor parks to the smoke-filled beer parlors, his Apala carried the stories, frustrations, and secrets of a city that never slept. Every drumbeat, every chant, every verse seemed to challenge the listener—sometimes comforting, sometimes warning.

He was more than a singer. He was a social conscience for the forgotten, the cultural prophet of the underclass. His music was as rough as gravel, yet it carried poetry that cut through hypocrisy. Ayinla had made Apala more than entertainment; he had made it a battlefield.

What happened that night is not merely the death of a man. It was the collapse of an entire soundscape. To understand how, we must walk back into his life—into the dust and rhythm of Apala, the restless mood of 1970s Abeokuta, and the combustible personality that made Ayinla Omowura both untouchable and tragically vulnerable.

One: Born in Dust, Raised by the Streets

In 1933, Waidi Ayinla Omowura was born in Itoko, a district in Abeokuta where poverty was not an accident but a permanent condition. Unlike the children of the educated elite who would later dominate Nigeria’s politics, Ayinla’s childhood was molded by scarcity and survival.

School and Ayinla were never friends. He dropped out early, preferring the pulse of the streets to the order of classrooms. This decision, though seen as foolish at the time, was the beginning of his transformation. Because the streets were his university. The markets were his libraries. The touts, butchers, and traders were his classmates. And their language—their anger, their humor, their resilience—became the foundation of his music.

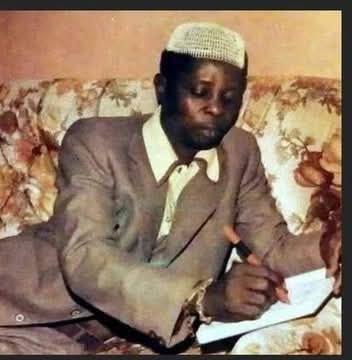

In his youth, he flirted with trades—tailoring, driving, even blacksmithing—but none held him. What he found irresistible was the drum. The Yoruba talking drum (gangan), with its ability to mimic speech, became his closest companion. He listened to the older Apala players in Abeokuta, soaking in the rhythms of Haruna Ishola and others who had made the genre respectable.

But respectability was not Ayinla’s ambition. His Apala would not sound like the polished melodies of Haruna. His Apala would be fire—raw, unrefined, weaponized. It would be the kind of music you could hear over the chaos of a motor park, the kind of sound that demanded attention even when you tried to ignore it.

By his twenties, Ayinla had started singing in local joints, his voice already showing the gravelly force that would later define him. People laughed at first—his sound was too rough, too untrained. But the same rawness that made elites sneer made the working poor see him as theirs. He sounded like them. He sang like their frustrations.

And slowly, Abeokuta began to notice.

Abeokuta in the 1970s – A City of Clenched Fists

To grasp Ayinla’s rise, one must picture Abeokuta not as the serene city of Olumo Rock postcards, but as a restless urban sprawl where tension and tradition collided.

The oil boom of the 1970s had enriched Lagos, but Abeokuta remained a city of hustlers. Drivers and conductors ruled the motor parks with fists and insults. Butchers carried knives not just for cows but for settling scores. Soldiers, drunk with their newfound authority in Nigeria’s military era, clashed frequently with civilians. And in the middle of this chaos were the beer parlors—crowded, smoky, noisy theaters of Yoruba masculinity.

Here, music was not just entertainment. It was currency. Musicians like Ayinla were not distant stars; they were street philosophers whose lyrics were debated like political manifestos. Every line mattered. Every drumbeat was loaded.

Ayinla’s genius was that he took the mood of Abeokuta—the suspicion, the competitiveness, the rough humor—and turned it into song. Where Lagos Juju musicians sang for elites in glittering halls, Ayinla sang for men with dust on their clothes and anger in their throats. His Apala became the official sound of the ordinary Abeokuta man.

But with this popularity came danger. Because in a city of clenched fists, a man who sang too sharply was bound to cut not just his enemies but himself.

Apala as Sword and Shield

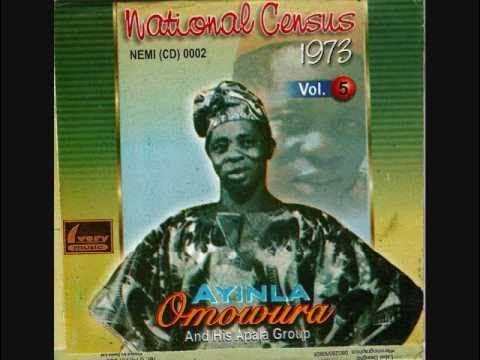

Apala music had humble beginnings. In the 1940s, it was used during Ramadan to wake Muslims for fasting. Over time, it moved beyond its religious roots into secular entertainment. But Ayinla transformed it into something else entirely: a weapon.

He sharpened Apala into a tool of confrontation. His lyrics mocked rivals with devastating wit. He could expose hypocrisy with a single verse, leaving opponents humiliated in public. His songs became like letters to society—sometimes praising, often scolding, always provocative.

Unlike Haruna Ishola, who kept Apala smooth and diplomatic, Ayinla relished its roughness. He embraced his voice’s harsh edge, leaning into it until it became his signature. His band, the Apala Group, built rhythms that seemed designed to provoke as much as to entertain.

By the mid-1970s, Ayinla had released albums that turned him into a Yoruba folk legend:”National Population Census” and “Challenge Cup ’74, among others. Each album was more than music—it was social commentary set to drumbeats. Drivers, butchers, and market women quoted his lines in arguments the way politicians quoted laws.

But his sharp tongue made him enemies. He attacked rivals mercilessly, mocked colleagues without restraint, and carried his quarrels from music into everyday life. The same Apala that gave him power was pulling him toward danger.

Ayinla the Man – A Lion with No Leash

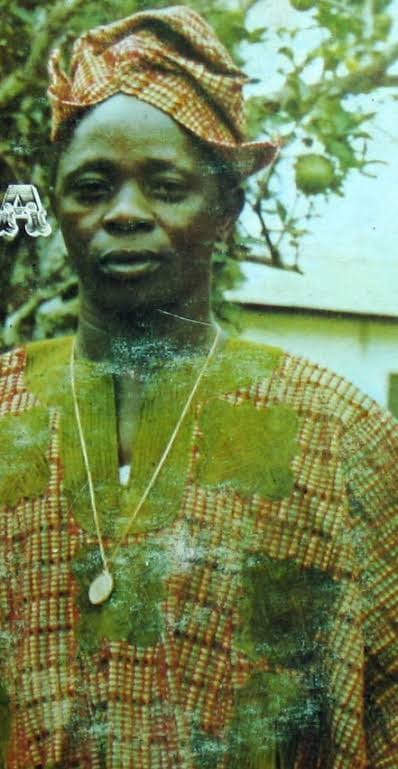

To understand why that fatal night unfolded as it did, one must look at Ayinla the man, not just the musician.

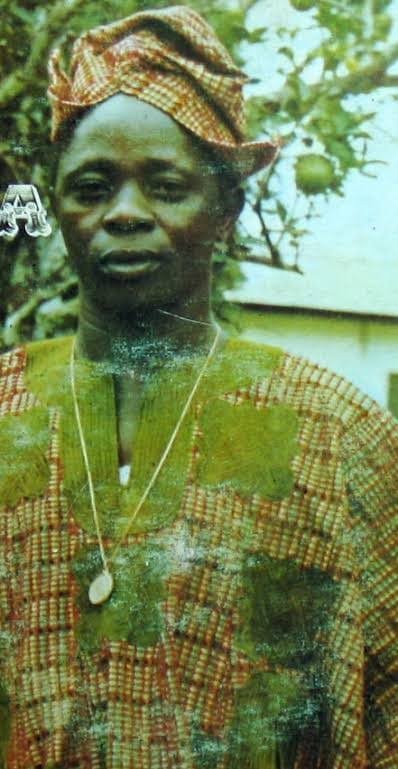

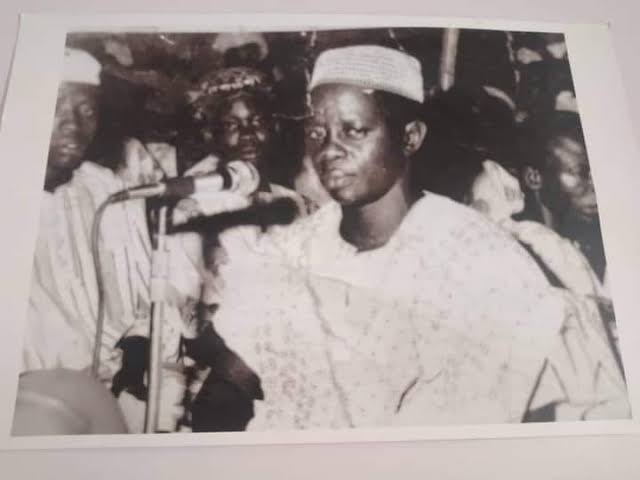

He was flamboyant—his clothes bright, his jewelry heavy, his swagger unmistakable. In Abeokuta, you could not mistake Ayinla when he walked into a bar. He demanded attention the way a lion demands silence in the forest.

But he was also hot-tempered. Insults were unforgivable, slights became vendettas. He was fiercely loyal to his friends but merciless to his enemies. Even within his band, quarrels simmered. His band manager, Fatai Bayewunmi, had once been a trusted ally, but their relationship grew increasingly toxic—soured by money, ego, and authority.

Those who knew him said Ayinla was both loved and feared. He could be generous one moment and vicious the next. In many ways, he embodied the contradictions of Abeokuta itself—proud, volatile, restless.

This combustible mix was always going to explode. The only question was when, and how.

The Night of May 6, 1980

That night began in the usual way: with drinks, with music, with arguments too small to matter until they grew too large to stop.

In one of Abeokuta’s beer parlors, Ayinla and Bayewunmi clashed. The argument was over money and control—two things that had long poisoned their relationship. Voices rose. Insults flew. Chairs shifted nervously as patrons sensed danger.

And then it happened.

Bayewunmi reportedly grabbed a beer glass, smashed it against the table, and in one furious motion drove the jagged edge into Ayinla’s head. Gasps filled the room. The lion of Apala staggered, blood spilling onto the dusty floor. His eyes, once fierce, dimmed with shock, as widely reported.

The bar erupted in chaos. Some screamed. Some fled. Loyalists rushed to his side, carrying him toward the hospital. But the wound was fatal. By the time they arrived, the man whose voice had shaken Abeokuta for decades was gone.

Apala died that night—not only in the body of its fiercest prophet but in the silence that followed.

Mourning in Abeokuta

The next morning, Abeokuta was unrecognizable. The markets were subdued, the motor parks eerily quiet. Radios played his songs not in celebration but in mourning. Women wailed in the streets. Men shook their heads in disbelief.

Thousands thronged his funeral, some collapsing in grief. His grave became an instant shrine, a place where fans whispered prayers and poured libations. For the working poor, it felt as though a part of their own soul had been ripped away.

His death was more than a personal tragedy. It was a communal wound. Apala had lost its fiercest warrior, and Yoruba culture had lost one of its boldest voices.

The Trial of Betrayal

The courts became the theater for Act Two of the tragedy. Bayewunmi, once Ayinla’s confidant, now stood accused of murder. The proceedings fascinated Ogun State. Newspapers carried every detail, every testimony, every legal twist.

The irony was bitter: the man who had once managed Ayinla’s career now stood as the man who ended it.

The verdict was inevitable. Bayewunmi was reportedly sentenced to death. Justice, perhaps, but not healing. For fans, the trial was only a reminder that the lion had been slain not by strangers, but by one of his own.

A Wounded Genre

Without Ayinla, Apala limped. Haruna Ishola carried the torch briefly, but his death in 1983 left the genre orphaned. Meanwhile, Fuji—led by Sikiru Ayinde Barrister and Wasiu Ayinde—was rising fast, sweeping the Yoruba music scene with its energy and adaptability.

Apala became heritage rather than mainstream. Its raw, confrontational power was buried with Ayinla in Abeokuta soil.

The Legacy That Refuses to Die

More than four decades later, Ayinla Omowura is still spoken of in reverence. His music remains timeless, his voice immortalized on vinyl, his life retold in folklore. In 2021, filmmaker Tunde Kelani brought him back to life on screen, reminding younger generations of the man who turned Apala into both sword and shield.

But beyond the nostalgia lies the warning: Ayinla’s story is the story of Nigeria’s contradictions—talent consumed by temper, genius undone by violence.

The night he died, Abeokuta did not just lose a man. Yoruba music lost a heartbeat. And Apala, though still alive in recordings and memories, has never truly recovered.

Final Thoughts: The Blood and the Drum

History remembers May 6, 1980, as the night Apala died.

Not because the genre ceased to exist, but because it lost the man who had given it its fiercest roar. In Abeokuta’s memory, that night is not just about broken glass and spilled blood. It is about the silencing of a rhythm that once made the streets throb with defiance.

And so, whenever an old Ayinla record spins in a beer parlor, one can almost hear the echo of that night—the night when a city gasped, a voice went silent, and a drumbeat fell into eternal pause.