In 1970s Lagos, Fuji was more than music—it was a movement. At its center stood two men: Sikiru Ayinde Barrister, the pioneer who turned Islamic wéré chants into a modern genre, and Kollington Ayinla, the fiery General who gave Fuji its raw, percussive edge.

What began as friendship soon hardened into rivalry. Their lyrics became weapons, their concerts battlegrounds, and their fan bases rival factions. The feud was so fierce that it spilled beyond nightclubs and record shops, seeping into Nigeria’s social life, politics, and even its movies.

This is the story of how two musical giants, bound by culture but divided by ego, waged a war of drums and words that not only redefined Fuji but etched their conflict into Nigeria’s cultural memory.

From Wéré to Fuji: The Cultural Roots

Fuji music’s story begins not in grand concert halls but in the quiet, predawn streets of Yoruba towns. Derived from wéré music, a genre performed during Ramadan to wake Muslims for Sahur (the pre-dawn meal), Fuji was rooted in religious devotion, community cohesion, and rhythmic complexity.

The genre borrowed from apala and juju styles, incorporating percussion patterns, melodic chants, and call-and-response structures that mirrored Yoruba oral traditions.

Sikiru Ayinde Barrister and Kollington Ayinla were not just musicians—they were innovators translating centuries-old cultural practices into contemporary expressions. Barrister’s approach emphasized lyrical improvisation and vocal dexterity, often layering social commentary with humor and praise for patrons. Kollington, on the other hand, brought a militaristic precision to his beats, introducing the bata drum’s commanding presence into Fuji’s rhythmic foundation.

Their simultaneous innovations positioned them as giants of the same emerging musical empire—but in time, the empire would fracture.

Early Lives and Musical Awakening

Sikiru Ayinde Barrister was born in 1948 in Lagos. His childhood was steeped in music: he learned percussion from neighborhood elders and practiced call-and-response chants that would later define his performance style. By his teens, Barrister had begun to compose songs that blended wéré traditions with contemporary instruments, setting the stage for the Fuji revolution.

Kollington Ayinla, born a few years earlier in Ibadan, had a different path. Coming from a family with deep ties to Yoruba spiritual and musical traditions, Kollington’s early exposure to bata drums and folk storytelling honed his sense of rhythm and narrative. By the time he released his first album in the 1970s, he had already cultivated a following devoted to his dynamic, energetic style.

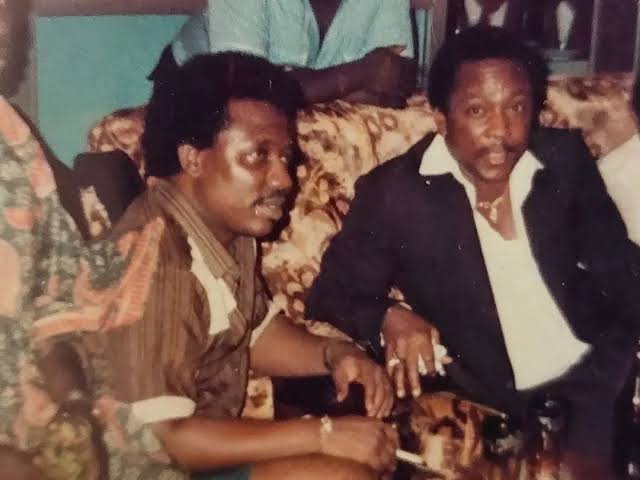

The two would cross paths in Lagos’ burgeoning live music scene. Initially collaborators and friends, they performed together in community events and shared stages in local nightclubs. Both were ambitious, both talented—and both destined for legendary status. But ambition, as it often does, sows the seeds of rivalry.

The Feud Ignites

The first cracks in their friendship appeared in the late 1970s. As Fuji gained commercial traction, record labels sought to capitalize on the genre’s rising popularity. Both artists were courted aggressively, and disputes over contracts, album rights, and musical style began to surface.

Barrister accused Kollington of borrowing rhythms without acknowledgment, while Kollington believed Barrister had co-opted lyrics that were originally his compositions.

Their rivalry spilled into the public arena. Fans were polarized. Neighborhoods aligned with one or the other, creating a musical faction system that mirrored political partisanship. In interviews, subtle digs became open criticism. Albums released in the early 1980s carried veiled messages, sometimes in Yoruba, that fans immediately recognized as thinly veiled attacks.

The feud intensified during a 1983 performance at the National Theatre. Both men were invited to headline a major Fuji event intended to celebrate the genre. Barrister’s troupe performed first, delivering a set brimming with improvisation, praise-singing for his patrons, and indirect jabs at Kollington.

The crowd roared in approval, but when Kollington took the stage, his performance escalated the tension. Drums thundered, lyrics sliced through the air like blades, and for the first time, the musical battle was unmistakable: two philosophies, two styles, two egos, clashing under the bright lights of Lagos.

Albums as Armaments

In the 1980s and 1990s, Barrister and Kollington released a series of albums that served as both musical innovation and personal commentary.

Barrister’s Fuji “Iwa” (1982) and “Nigeria” (1983) albums showcased vocal experimentation and social storytelling, highlighted societal issues while subtly critiquing Kollington’s style.

Kollington responded with his albums blended traditional percussion with streetwise lyricism aimed at asserting his dominance in the Fuji hierarchy.

Music critics of the time noted the rivalry not only drove innovation but also shaped the genre itself. Each album pushed the boundaries of rhythm, vocal delivery, and lyrical content. The feud became a creative engine—though one fueled by tension, ego, and pride.

The Feud on Screen: Movies and Documentaries

Fuji music’s popularity eventually caught the attention of Nigeria’s film industry. Nollywood, then in its early stages, began incorporating Fuji soundtracks to enhance realism and appeal to urban audiences.

Barrister’s music appeared in several films, often underscoring narratives of ambition, betrayal, and resilience—themes that mirrored his own career.

Kollington’s influence also extended to cinema, particularly in films depicting Yoruba cultural life. Directors recognized that including tracks from the “General” added authenticity and emotional depth.

In 2024, the documentary Mr. Fuji: Barry Wonder revisited the feud, offering interviews, archival footage, and analyses of both men’s contributions. The film highlighted not only the artistry but the human conflict at the heart of Fuji music, showing how personal rivalry had artistic consequences for an entire generation.

Beyond Rivalry: Personal Struggles and Humanity

While public perception framed the feud as antagonistic, those close to the artists understood its complexity. Both men faced financial pressures, familial responsibilities, and the psychological toll of fame.

The late Barrister struggled with maintaining his troupe and innovating within a rapidly commercializing music industry. Kollington contended with expectations from loyal fans and the constant pressure to surpass Barrister’s innovations.

Friends and collaborators reported moments of reconciliation—shared meals, backstage discussions, and mutual acknowledgment of talent. But ego, pride, and public perception often prevented lasting resolution. The feud, in many ways, reflected the duality of human ambition: the drive to innovate coupled with the fear of being overshadowed.

Legacy: Shaping Fuji and Nigerian Culture

Today, the legacies of Sikiru Ayinde Barrister and Kollington Ayinla are intertwined. Their rivalry fueled a golden era of Fuji music, setting standards for creativity, showmanship, and musical complexity. Younger artists studied their albums, learning not only rhythm and melody but also the art of audience engagement, stagecraft, and lyrical subtlety.

The feud also influenced Nigerian cinema, as filmmakers sought to capture the tension and drama inherent in Fuji music. Films, documentaries, and stage adaptations continue to explore the personal and artistic dynamics that made the genre culturally significant.

Most importantly, the Barrister-Kollington feud illustrates a broader cultural truth: rivalry can be both destructive and generative. While it caused personal stress and public division, it also accelerated innovation, leaving an enduring imprint on Nigeria’s musical and cinematic landscape.

Closing Reflection: Music, Conflict, and Cultural Memory

The story of Sikiru Ayinde Barrister and Kollington Ayinla is more than a tale of rivalry—it is a study in creativity, cultural adaptation, and human complexity.

Their feud demonstrated how personal conflicts can shape artistic legacies, influence entire genres, and ripple through generations. It reminds us that music is never just sound; it is identity, expression, and, sometimes, battlefield.

As fans continue to play their albums, analyze lyrics, and revisit performances, the Barrister-Kollington rivalry lives on—not as a mere historical footnote but as a testament to the enduring power of music to define, challenge, and inspire. Fuji music, forever marked by this clash of titans, remains vibrant, evolving, and deeply embedded in Nigeria’s cultural memory.