The year was 1971, and Lagos was a city gasping under the weight of its own contradictions. Soldiers manned checkpoints at street corners as though they were permanent statues of authority. At Bar Beach, crowds gathered for the gruesome theater of firing squads, the waves of the Atlantic swallowing the last cries of the condemned. In another part of the city, near Surulere, danfos rattled through dusty roads, molues swayed with the weight of passengers, and all paths seemed to converge on one restless heart: Ojuelegba.

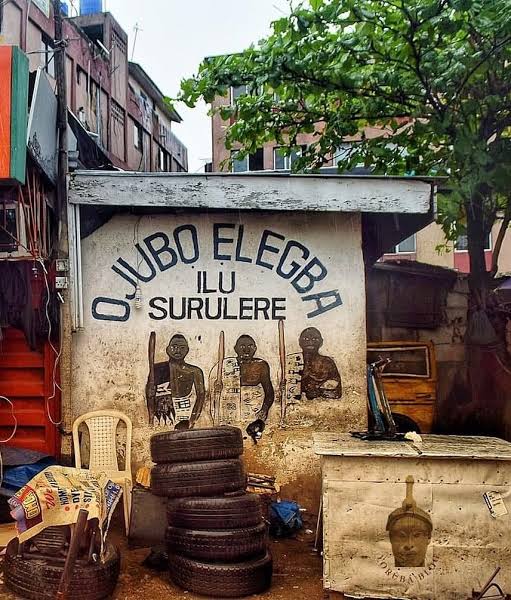

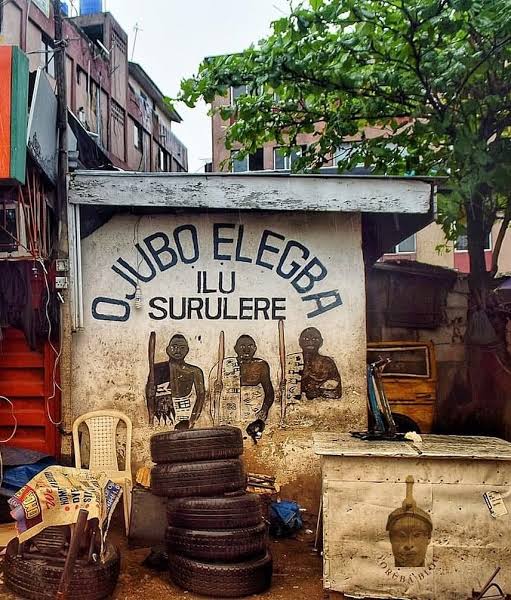

To passersby it was a roundabout, noisy and chaotic, a junction where buses competed for space and vendors hawked goods under the unforgiving sun. But Ojuelegba was more than asphalt and traffic. It was a shrine once dedicated to Elegba, the Yoruba guardian of crossroads, a place of spiritual power where the fate of travelers and traders was negotiated.

Decades later, when a boy born in Surulere named Ayodeji Ibrahim Balogun—the world would come to know him as Wizkid—sang about Ojuelegba, he was not simply paying tribute to a neighborhood. His voice carried the echoes of Lagos under martial law: nights of curfews, afternoons of police raids, and the ceaseless struggle of ordinary Lagosians to make a living under the shadow of soldiers.

To understand Wizkid’s “Ojuelegba” is to travel back to Lagos in the 1970s, a city gripped by military decrees yet still beating with the rhythms of Yoruba resilience, Afrobeat rebellion, and the raw energy of survival.

Ojuelegba Before the Generals

The origins of Ojuelegba reach far beyond Lagos’s highways and danfos. Long before modern Lagos became a capital of commerce and chaos, this crossroads was sacred ground. Among the Awori people, the area was known as Ojú-Ìbọ Elégbua—literally, “the shrine of Elegba.” Elegba, or Eshu Elegbua, was the Yoruba deity of chance and thresholds, the trickster who guarded doorways and determined the outcome of journeys. To pass through Ojuelegba was to move under his gaze, to cross into a space where fate itself was negotiated.

The shrine stood near the place where roads intersected, a quiet patch of spiritual authority in a forested landscape. Devotees left palm oil and kola nuts in calabashes, seeking Elegba’s favor in their travels. Over time, as Lagos grew from colonial outpost into sprawling metropolis, the shrine was swallowed by urban sprawl. But even as asphalt covered the ground and bridges rose above it, the name remained—Ojuelegba, the place where destiny was bargained.

By the 1970s, the shrine still lingered on the periphery, half-forgotten but never erased, its presence felt more in the chaos of the streets than in the offerings left at its base. The spirit of Elegba lived on in the unpredictable traffic, the hustlers who made a living at the junction, and the musicians who found inspiration in its rhythm.

Lagos Under Military Boots

When Nigeria slipped into military rule after the 1966 coups and the subsequent civil war, Lagos became not just the political capital but also the stage upon which the drama of authoritarian power played out. By the early 1970s, General Yakubu Gowon ruled from Dodan Barracks in Ikoyi. Though Lagos glittered with oil wealth, it also bore the scars of corruption, population explosion, and infrastructural decay.

The military government, intent on stamping its authority, reshaped the city in both symbolic and brutal ways. In December 1971, under Brigadier Mobolaji Johnson, the colonial-era Ajele Cemetery on Lagos Island was bulldozed to make way for new government offices.

Among the graves destroyed were those of early Christian leaders like Bishop Samuel Ajayi Crowther, the first African Anglican bishop. Writers like Wole Soyinka condemned the act as a desecration of history. For Lagosians, it was a reminder that under military rule, even the dead were not safe from the reach of power.

But it was the spectacle at Bar Beach that etched military Lagos most deeply into memory. In 1971, the armed robber Babatunde Folorunsho was executed by firing squad on the sands of Victoria Island. Thousands gathered, some out of fear, others out of morbid curiosity, as the military turned death into public theater.

Over the years, the beach became synonymous with state violence. By the time General Murtala Mohammed was assassinated in 1976 and his killers were executed, the ritual of public death had become part of Lagos’s rhythm.

Ojuelegba, though a world away from the polished avenues of Victoria Island, felt the pulse of these events. Every decree, every execution, every show of state power rippled through the city, shaping the lives of those who hustled at the crossroads.

Ojuelegba in the 1970s: Chaos and Culture

If the generals sought order through fear, Ojuelegba responded with chaos of its own. By the 1970s, the roundabout had transformed into a teeming hub of nightlife and survival. It was the gateway into Surulere, where middle-class families lived alongside hustlers and musicians. The area’s notoriety grew as it became a haven for crime and vice, especially around Ayilara and Clegg Streets.

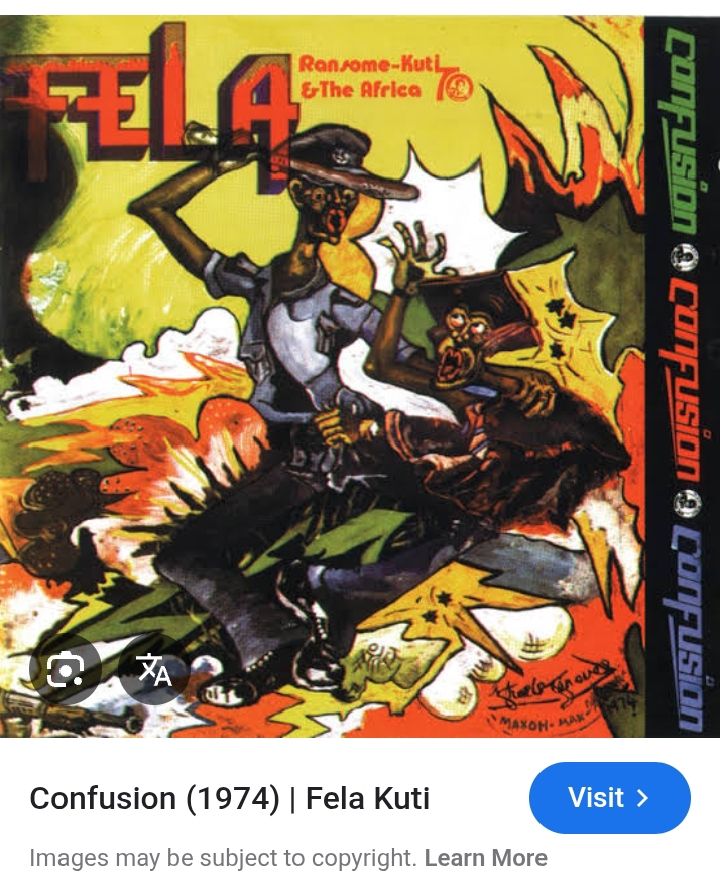

It was also the pathway to Fela Kuti’s music hub. Just off Ojuelegba, at Moshalashi in Surulere, Fela established his nightclub, the Shrine, where he performed night after night. His Afrobeat anthems—blending Yoruba rhythms, jazz horns, and biting political commentary—captured the confusion of the city. In his 1974 track “Confusion,” Fela described Ojuelegba in vivid terms: a junction where cars from every direction collided and policemen were nowhere to be found. For him, Ojuelegba was Lagos in miniature: a place where order broke down, where survival meant navigating chaos with wit and rhythm.

The military despised Fela’s open criticism. His Kalakuta Republic was raided multiple times, his mother thrown from a window during one brutal attack in 1977. Yet, even in the face of soldiers’ boots and guns, Ojuelegba remained alive with music, its streets echoing with the defiance of Afrobeat.

Surulere’s Children

By the time Wizkid was born in 1990, the military era was in its final years, but its shadows lingered. He grew up in Surulere, just a short walk from the heart of Ojuelegba. The neighborhood was no longer just a shrine or a crime hub—it had become a metaphor for the hustle of Lagos life. The children of Ojuelegba learned early that survival required grit, luck, and divine favor.

Wizkid, one of many children in a modest polygamous household, found his calling in music. He sang in church, recorded his earliest tracks in the backrooms of Surulere, and absorbed the rhythms of the street. Ojuelegba was both his classroom and his proving ground, a place where he saw men struggle, women trade, buses collide, and dreams either die or take flight.

When he recorded “Ojuelegba” in 2014, it was a song born of memory. The lyrics spoke of hunger, of nights when he walked through the streets wondering if his music would ever be heard, of friends who did not make it, and of the divine favor that allowed him to escape. The song was not just personal—it was a mirror of the city’s history. Behind every line lay the ghosts of the 1970s: the soldiers who enforced curfews, the criminals executed at Bar Beach, the musicians who fought with rhythm against repression.

The Legacy of Military Lagos in Wizkid’s Ojuelegba

What makes Wizkid’s “Ojuelegba” resonate so deeply is its layered inheritance. At one level, it is the story of a boy from Surulere who rose to global stardom. At another, it is the voice of a city that has survived dictatorship, erasure, and chaos.

Ojuelegba carries within it the memory of Elegba’s shrine, where fate was bargained; the memory of Bar Beach, where life could be ended by decree; the memory of Fela’s Afrobeat rebellion, which transformed chaos into art. Wizkid’s voice, smooth and unassuming, channels all these histories into a single narrative of survival and triumph.

The song also symbolizes Lagos’s paradox. In the 1970s, the military tried to impose order through violence, yet Lagos thrived on disorder. Ojuelegba, chaotic and unpredictable, became the perfect metaphor for the city itself. Wizkid’s choice to name his anthem after this place was not accidental. It was an acknowledgment that to be from Lagos is to be from Ojuelegba: a crossroads of fate, survival, and possibility.

Wizkid’s “Ojuelegba”: A Modern Reflection

Wizkid’s “Ojuelegba” emerges as a modern reflection of the struggles and aspirations of the Nigerian people. The song’s lyrics, “Ni Ojuelegba, they know my story,” resonate with many who have experienced the hardships of life in Lagos. Wizkid’s journey from the streets of Ojuelegba to international stardom mirrors the resilience and determination of those who continue to fight for a better future.

The music video further emphasizes this connection, showcasing scenes of everyday life in Ojuelegba, from bus rides to street vendors. These visuals not only highlight the vibrancy of the neighborhood but also serve as a reminder of the challenges faced by its residents.

Final Takeaway: The Crossroads Eternal

Today, the Ojuelegba bridge still stands, its traffic as unrelenting as ever. The shrine of Elegba, tucked away, continues to receive offerings from devotees who remember its ancient power. On the streets, vendors hawk goods, danfos screech to a halt, and hustlers carve out a living. For most, Ojuelegba is just another Lagos junction. But for those who know its history, it remains a place where the spiritual, the political, and the personal converge.

Wizkid’s “Ojuelegba” is more than a hit song—it is an heirloom of the city’s memory. In its rhythm one can hear the echoes of firing squads at Bar Beach, the wail of Fela’s saxophone, the chants of worshippers at the shrine, and the cries of children growing up under curfews. It is a reminder that even under the shadow of generals, Lagos found a way to sing.

Ojuelegba endures because it is more than geography. It is Lagos itself: unpredictable, defiant, alive.