The hum of generators hummed like a restless orchestra. The night sky over Lagos was punctuated by candlelight in some homes and the faint blue glow of kerosene lamps in others. Radios hissed and crackled, cutting through the layered noise of a city never at rest. It was the mid-1990s, and Lagos was drowning in its own contradictions: the hope of democracy colliding with the suffocation of military decrees, the ingenuity of hustlers competing with the brutality of survival.

- Lagos, 1990s: A City Unruly and Alive

- Gbenga Adeboye’s Rise: From Ode-Omu to Lagos Airwaves

- Satire Meets History: Real Events Through a Comic Lens

- Lagos Hustle as Satire

- The Paradox of Laughter in Darkness

- A Nation Holds Its Breath: Death, Resurrection, and Final Goodbye

- Legacy: Lagos After Funwontan

- Final Thoughts: Lagos, Still Laughing

And then, amid the chaos, a voice spilled into the night. It wasn’t the stern command of a soldier or the hollow promises of a politician—it was Gbenga Adeboye, “Funwontan,” the satirist who had made it his mission to turn Lagos inside out with laughter. His baritone was smooth yet sharp, weaving stories where pastors, landlords, market women, and political leaders collided in sketches so hilarious they forced listeners to choke on their own truths.

Adeboye’s satire was not ordinary comedy. It was Lagos itself, refracted through wit, irony, and mimicry. He captured the frustrations of commuters trapped in endless traffic, the exasperation of tenants bullied by landlords, the sanctimony of pastors selling miracles, and the fragile hope of a nation searching for freedom. In a city teetering on the edge of madness, he made laughter both a survival strategy and a weapon of critique.

This is the story of Lagos in the 1990s—not as history books will tell it, but as Gbenga Adeboye’s satire carved it into memory. A city where jokes doubled as resistance, where mimicry became philosophy, and where one man’s laughter carried the weight of a million frustrations.

Lagos, 1990s: A City Unruly and Alive

To grasp Adeboye’s satire, one must first understand the Lagos he lived in.

The 1990s were turbulent years for Nigeria. The annulment of the June 12, 1993, elections—the fairest in Nigeria’s history—triggered mass protests and unrest. Military dictator Sani Abacha ruled with an iron fist, filling prisons with dissidents while the city streets filled with soldiers wielding horsewhips. Lagos, the country’s commercial capital, was the epicenter of both resistance and repression.

In Lagos Island’s markets, traders cursed NEPA (the electricity board) for plunging stalls into darkness while demanding payment for phantom light. In Ojuelegba and Oshodi, conductors screamed “Enter with your change o!” while dangling from rickety yellow buses, daring death at every turn. The city was bursting at the seams—its population swelling past 7 million, its infrastructure groaning, its resilience unbroken.

Survival was not optional; it was a daily duel. Traffic jams stretched into hours-long standstills. Hawkers turned gridlocks into mobile markets, selling everything from sachet water to wall clocks through bus windows. Floods after rainstorms turned streets into brown rivers, swallowing shoes and pride. Yet Lagos thrived—not in spite of its chaos, but because of it.

This was the Lagos Gbenga Adeboye saw, heard, and amplified through satire. Every sketch of his was a mirror to the city: a place at once exhausting and exhilarating.

Gbenga Adeboye’s Rise: From Ode-Omu to Lagos Airwaves

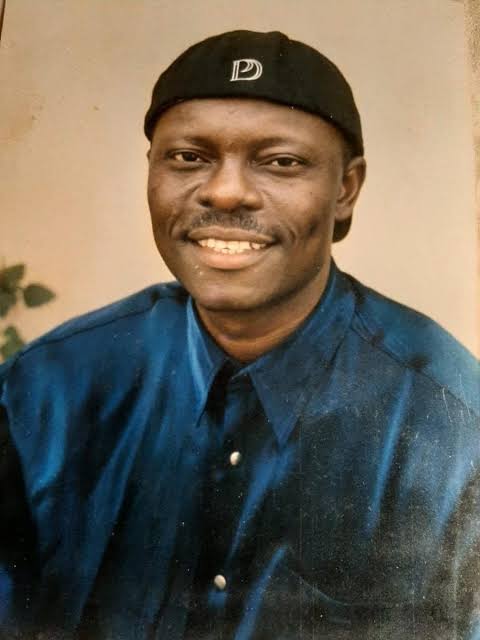

Born in 1959 in Ode-Omu, Osun State, Adeboye was not born into privilege. He navigated early life with grit, determined to carve a path through storytelling and performance. He had an instinct for mimicry from childhood, entertaining peers by imitating elders with uncanny accuracy.

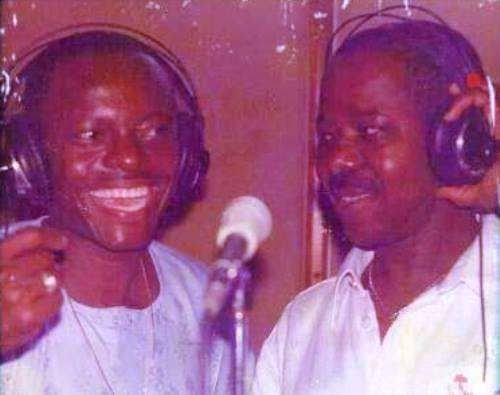

By the 1980s, Lagos’s airwaves became his stage. He joined the Lagos State Broadcasting Corporation, where his creativity earned him a cult following. Soon he was “Funwontan Oduology”—a man whose skits blended humor with Yoruba proverbs, whose voice alone could draw crowds to transistor radios in living rooms, shops, and bus parks.

Adeboye’s genius lay in his range. He could play a sanctimonious pastor promising miracle breakthroughs one minute and switch seamlessly into the gravelly voice of an area boy the next. He built entire worlds out of sound—marketplaces alive with bargaining voices, homes filled with landlord-tenant quarrels, traffic jams punctuated with conductor curses. His shows became Lagos itself in compressed form, delivered in 30-minute doses.

But his satire was not just entertainment—it was critique. Adeboye understood that in a city like Lagos, jokes were never just jokes. They were weapons, shields, and sometimes, confessions.

Satire Meets History: Real Events Through a Comic Lens

l) The June 12 Crisis

When Moshood Abiola’s presidential victory was annulled in 1993, Lagos erupted. Protesters filled the streets, soldiers unleashed violence, and uncertainty thickened the air. Adeboye responded with sketches that mocked the absurdity of political betrayal. Through parodies of politicians making empty promises, he exposed the disconnect between rulers and the ruled. Laughter became a safe way to confront fear.

ll) The Abacha Years

During Abacha’s dictatorship, Lagos existed in a climate of silence and whispers. But Adeboye spoke loudly, if indirectly. His satires of greedy landlords and corrupt pastors doubled as metaphors for the state’s authoritarian grip. His audiences understood the code: the “pastor” swindling his flock was not just a religious leader, but a stand-in for military rulers bleeding the nation dry.

lll) Ife–Modakeke Conflict

Ethnic tensions flared between the neighboring Yoruba communities of Ife and Modakeke throughout the 1990s. Adeboye, deeply rooted in Yoruba culture, used his platforms to lampoon the senselessness of fratricidal wars. In sketches where rival families fought over trivialities, he urged unity disguised as comedy, easing tension through reflection.

lV) The Japa Syndrome

Even in the 1990s, the “japa” dream—emigration for better opportunities—was alive. Adeboye mocked those who abandoned Lagos only to face disillusionment abroad. His parodies featured migrants calling home with exaggerated foreign accents while secretly struggling as janitors. The laughter cut deep, reminding listeners that escape was not always salvation.

V) Religion and the Prosperity Gospel

The 1990s also marked the boom of Pentecostalism in Lagos. New churches sprang up weekly, promising miracles, wealth, and instant transformation. Adeboye’s most famous parodies featured flamboyant pastors selling blessings like market goods. Listeners howled with laughter, but they also recognized the uncomfortable truth: faith had become commercialized, and Lagosians were desperate enough to buy it.

Lagos Hustle as Satire

What distinguished Adeboye most was his gift for embodying everyday Lagosians.

He mimicked bus conductors with uncanny precision—their nasal drawls, their impatience, their hustler instincts. Anyone who had taken a molue bus from Oshodi to CMS recognized the voices instantly.

He became the market woman, haggling ferociously, throwing in curses as bonus merchandise. He became the landlord, pompous and overbearing, demanding rent from tenants despite leaking roofs and broken plumbing. He became the NEPA official, threatening disconnection while ignoring pleas of innocence.

Through these characters, Adeboye held up a satirical mirror: Lagos was not only its rulers, but its hustlers, cheats, survivors, and dreamers. He exposed corruption not just in government offices, but in everyday life. Lagos was everyone’s theatre, and everyone played a part.

The Paradox of Laughter in Darkness

Why did Lagosians cling so tightly to Adeboye’s satire? Because laughter was survival.

Military decrees could silence newspapers. Soldiers could break protests with gunfire. But jokes? Jokes slipped through the cracks of repression, weaving their way into homes and bus stops. Adeboye gave people permission to laugh at their pain, to recognize themselves in absurdity, to find dignity in mockery.

In a city where the lights often went out, laughter was its own kind of power supply.

A Nation Holds Its Breath: Death, Resurrection, and Final Goodbye

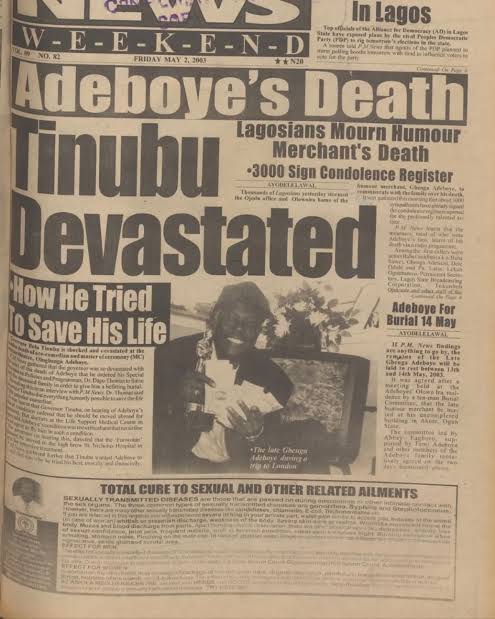

In October 2002, news spread that Gbenga Adeboye had died. Lagos mourned. Then, astonishingly, he returned six hours later, claiming divine reprieve. For a city accustomed to strange happenings, this was unprecedented—a satirist cheating death itself. His audiences celebrated, declaring him untouchable, a man whose humor even heaven could not silence.

But on 30 April 2003, the laughter ended. Adeboye died at just 44, left Tinubu, King Sunny Ade, Lagos bereft. His burial two weeks later turned into a spectacle that froze the city. From Ikeja to Akute, thousands abandoned their shops, offices, and homes to pay their respects. Traffic stood still. A city known for its restlessness paused.

It was the ultimate tribute: Lagos itself shutting down for its satirical conscience.

Legacy: Lagos After Funwontan

After his passing, the baton passed to a new generation— Ali Baba, Basketmouth, AY, Gbenga Adeyinka. Each owed a debt to Adeboye’s trailblazing blend of satire, mimicry, and commentary.

But something shifted. In the 1990s, satire was radio-based, communal, analog. By the 2000s, it had become televised and commercial. By the 2010s, it was online—short skits on YouTube and Instagram.

Today, Twitter memes lampoon politicians within minutes of their gaffes. Yet beneath the hashtags lies Adeboye’s DNA: the belief that humor is resistance, and satire is memory.

Final Thoughts: Lagos, Still Laughing

Lagos today glitters with skyscrapers, tech hubs, and global festivals. But peel back the gloss, and the old Lagos remains: traffic that eats hours, power outages that test patience, landlords that haunt tenants, and preachers who promise prosperity.

In these contradictions, Gbenga Adeboye’s voice still echoes. His sketches remain etched into the city’s cultural memory, reminding Lagosians that laughter can wound but also heal, that satire can both mock and teach, that sometimes, the only way to confront chaos is to laugh at it.

Lagos of the 1990s was unruly, unforgiving, and unforgettable. Through Gbenga Adeboye’s eyes, it becomes not just a memory, but a living mirror—a city that laughed its way through hardship, and in doing so, revealed its deepest truths.