There are nights in Nigeria’s memory where music and weather blur, when sound seems to summon sky. Among those nights, one stands out—a stage in the late 1980s, a young man with dreadlocks and a guitar, singing words that carried both desperation and prophecy. The people listening were weary of drought, their fields cracked, their spirits dry. Yet as his chorus rose, something uncanny happened. The heavens opened, and rain fell—hard, cleansing, endless.

It was more than coincidence, at least to those who believed. For them, the song was a prayer answered, a voice powerful enough to shift the elements. The singer was Majek Fashek, and from that night, he was no longer merely a musician. He became The Rainmaker.

But the rain he summoned did not always fall kindly. It came in torrents of acclaim, then in floods of expectation he could not escape. It watered his fame, but also drowned his peace. It was both miracle and curse, falling on stages in Lagos, in New York, in Kingston, but also in rehab wards, lonely hotel rooms, and darkened hospital corners. The rain never stopped, but it did not always save him.

This is the story of Majek Fashek—the man who once sang down the rain and then lived beneath its storm for the rest of his life.

Roots in Benin City

Majekodunmi Fasheke was born in March 1963 in Benin City, Edo State, to a Yoruba father and an Edo mother. His name itself carried mystery. In Yoruba it was sometimes interpreted as “Ifa does not lie” or “powers of miracles,” words that hinted at destiny. Yet his upbringing was far from enchanted. His parents separated early, leaving his mother to raise him.

Benin City in the 1960s and 70s was a place where colonial legacies mixed uneasily with indigenous tradition. Music was everywhere—in markets, in churches, in neighborhood parties that went until dawn. For Majek, the church became his first stage. He sang in an Aladura congregation, learned the trumpet, and later guitar. The hymns and rhythms gave him discipline, but they also planted something deeper: the sense that music was not entertainment alone. It could be prophecy, prayer, and protest.

As a teenager, he became drawn to reggae—the Jamaican sound that spoke of exile, freedom, and African pride. Bob Marley’s voice reached him through vinyl records, but he also heard echoes in his own heritage. The pulse of reggae’s heartbeat rhythm, the call to liberation, matched the Yoruba and Edo folk traditions he grew up with. Music, for him, was never foreign. It was a global river flowing into local soil.

The First Bands and the Benin Sound

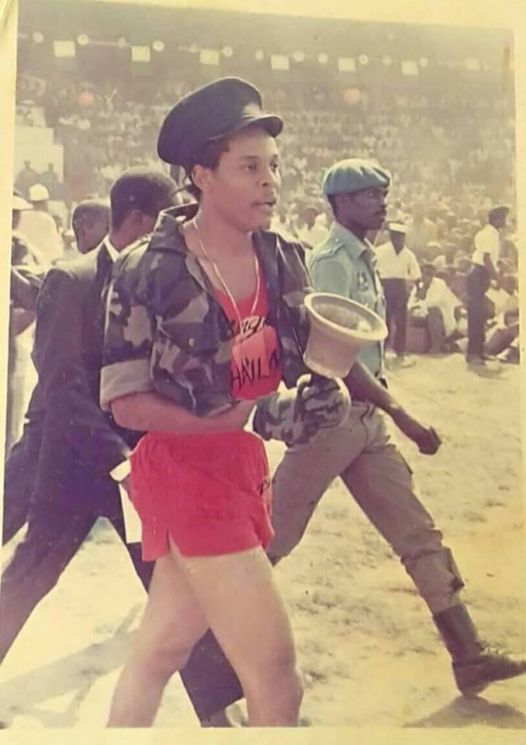

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Majek joined local groups. One was Jastix, alongside McRoy Gregg and Black Rice. The trio became familiar faces on Music Panorama, a Nigerian Television Authority (NTA) Benin program. Their sound was raw but magnetic. They toured with fellow rising star Onyeka Onwenu and backed up other performers.

But even then, Majek was restless. Jastix gave him a platform, but he craved a voice of his own. He began experimenting with what he later called kpangolo music—a fusion of reggae with Nigerian rhythms, juju guitar licks, Edo folk melodies, and Yoruba percussion. This hybridity would define him. He was not an imitator of Bob Marley; he was a Nigerian refraction of the reggae spirit, speaking in his own cadence.

Prisoner of Conscience

His breakthrough came with Prisoner of Conscience in 1988, released under Tabansi Records. The album was packed with socially conscious reggae, but one song eclipsed them all: Send Down the Rain.

Nigeria at that moment was wrestling with economic hardship and political uncertainty under military rule. Drought had bitten into parts of the country, and metaphors of dryness—both literal and spiritual—were common in everyday speech. When Majek sang Send Down the Rain, audiences did not hear only a tune. They heard a prayer.

Then came the legend: at concerts where he performed the song, skies broke open, and rain fell. Whether by coincidence or miracle, the association stuck. The song became a national anthem of sorts, and Majek became The Rainmaker. By 1989, he had swept the PMAN awards—Song of the Year, Album of the Year, and more.

The Rainmaker was now a star, not only in Nigeria but across Africa. His voice carried urgency, his guitar wept and thundered, and his dreadlocked figure recalled Marley, though his message was distinctly Nigerian.

Spirit of Love and International Reach

Majek’s fame soon crossed oceans. By 1991, he was recording in the United States. His album Spirit of Love, partly produced by Steven Van Zandt of the E Street Band, blended reggae with juju, talking drums, and American rock flourishes. Critics in the West saw him as Africa’s reggae prophet, a bridge between continents.

Concerts followed in Europe and America. His performances were fiery, sometimes unhinged, always memorable. He sang of apartheid, of poverty, of love and unity. In songs like So Long, Too Long, he addressed South Africa’s struggle, connecting Nigeria’s own political turmoil to the global fight for justice.

For a time, it seemed Majek might achieve what Fela Anikulapo-Kuti had in Afrobeat: becoming an international symbol of Nigeria’s cultural and political soul. The rain kept falling, and he danced under it, guitar in hand.

The Storm Within

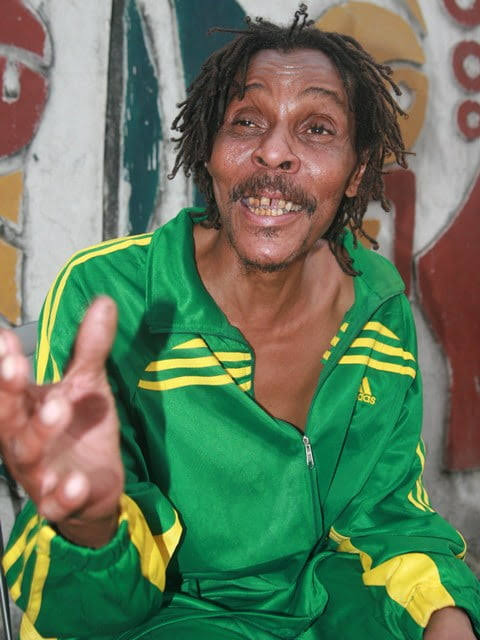

But fame is weather, not destiny. By the mid-1990s, Majek’s life began to unravel. Interviews and reports described heavy drinking, drug addiction, and mounting paranoia. His once-commanding voice grew raspy. His financial situation declined sharply.

Friends recalled him drifting between Lagos and New York, sometimes homeless, sometimes surviving on the kindness of strangers. His teeth decayed; his health faltered. In Nigeria, rumors circulated of his mental illness, of occult battles, of spiritual affliction. The Rainmaker seemed trapped in a storm of his own making, unable to step out of the downpour he had once commanded.

Attempts at comebacks came sporadically. In 1997, he released Rainmaker. Later efforts followed, but they never reached the force of his first two albums. The Nigerian music scene was shifting too, with Afrobeat’s revival, hip hop’s rise, and Afro-pop’s explosion. Majek belonged to another era.

The Rain as Metaphor

Rain in Majek’s story is never just weather. It is metaphor layered upon metaphor. It is hope in a parched land. It is justice delayed but not denied. It is spiritual renewal when everything feels broken. But it is also excess. Too much rain can flood fields, rot crops, drown villages.

In Majek’s life, the rain was blessing and curse. It lifted him from obscurity, crowned him a national prophet, but also drowned him in expectations he could not meet. Fans wanted miracles from a man battling demons. They wanted the skies to open at his command, forgetting that even the Rainmaker is mortal.

Decline and Public Pity

By the 2000s, stories of Majek’s decline dominated headlines. He was spotted begging in New York subways. Videos showed him disoriented, rambling. In Abuja, he was admitted to rehab. At one point, Nigerian billionaire Femi Otedola paid for his medical bills, a gesture of pity and respect rolled into one.

The Rainmaker had become a cautionary tale. To some, he embodied the tragedy of Nigerian musicians—brilliant, prophetic, but unsupported, left to waste under the weight of neglect. To others, his story was personal tragedy: a man undone by addiction and spiritual struggle.

Death in New York

On June 1, 2020, Majek Fashek died in his sleep in New York City. He was 57. The news rippled through Nigeria. Social media filled with tributes. Radio stations replayed Send Down the Rain. Old fans wept. Younger Nigerians, many of whom knew his name more than his music, searched his songs online and discovered the haunting voice of the Rainmaker.

Even in death, the rain metaphor returned. Tributes spoke of his spirit still watering the earth, of his music as eternal rainfall against injustice and despair. The man was gone, but the storm he summoned continued.

Legacy of the Rainmaker

Majek Fashek’s story is both triumph and tragedy, prophecy and warning. He showed that Nigerian music could command the world stage without losing its local soul. His blend of reggae, folk, and juju remains unique, a reminder that hybridity can be fertile ground.

But his life also reveals the fragility of artists in Nigeria and beyond. Fame does not guarantee stability. Prophets are rarely cared for in their lifetimes. The Rainmaker gave the people rain, but when drought struck his own life, few were there to shelter him.

His music, however, endures. In villages, children still sing Send Down the Rain when skies darken. In cities, his voice is remembered as one that carried truth to power. In the diaspora, he is part of the pantheon of African voices who made reggae an African tongue.

Leaving With This – The Sky’s Memory

The rain Majek Fashek called down never stopped falling. It came as applause, as fame, as burden, as tragedy. It fell on the dry fields of 1980s Nigeria and on the lonely hospitals of America. It fell as tears at his funeral, as streams replaying his songs, as memories retold in markets and living rooms.

Majek Fashek was not only the Rainmaker; he was the rain itself—unpredictable, nourishing, destructive, unforgettable. And as long as people look up to the sky, waiting for relief, his voice will echo: Send down the rain, do not let the drought have the last word.