On certain Lagos nights in the late 1960s, the city pulsed with a sound that was neither highlife nor jazz, neither funk nor traditional Yoruba drumming—but a restless collision of them all. The rhythm seemed to rise not just from the instruments, but from the city itself: the clatter of danfo buses, the smoky laughter of night traders, the rush of young men chasing dreams in a place where oil money was beginning to redraw the skyline. The air smelled of pepper soup, cheap gin, and cigarette smoke, but also of something heavier, more intoxicating—a new music, a new defiance, a new Lagos.

- The City Before the Sound

- The Nightclub as a Crucible

- The Nightclub as a Crucible

- Fela’s Restlessness

- The Afro-Spot’s Nights of Fire

- Seeds of Rebellion

- Across the Atlantic: America’s Echoes in Lagos

- The Afro-Spot Transforms into the Shrine

- Lagos as a Character in the Story

- The Afro-Spot and Its Patrons

- Government Suspicion and Crackdowns

- The Nightclub as University

- The Afro-Spot’s Sonic Legacy

- Global Expansion Without Borders

- The Afterlife of Afro-Spot in Lagos Nightlife

- The Symbolic Power of a Small Place

- Legacy Beyond Music

- Parting Words: The Beat Goes On

It was not born in daylight, nor in the polished concert halls that colonial elites had once cherished. Instead, it began in a dimly lit nightclub whose walls sweated as much as its dancers, a place where the city’s disenchanted youth, radicals, hustlers, expatriates, and dreamers all pressed shoulder-to-shoulder. There, one man and his band built a sound that refused to bow to colonial memory or military rule. A sound that did not just entertain but unsettled, questioned, and demanded.

The nightclub did not look like the cradle of a revolution. Yet within its smoke-stained walls, Afrobeat found its first heartbeat—long before the genre conquered London, Paris, New York, and beyond. This was Lagos in transition, a city becoming the restless capital of Black identity, and in its hidden corners, the rhythm of resistance began to echo.

The City Before the Sound

To trace Afrobeat’s nightclub origins, one must first recall Lagos in the late 1960s. This was no ordinary African city. It was a melting pot of histories and contradictions, a place where Portuguese colonial relics still lingered in architecture, where Brazilian returnees carried samba and Catholic traditions back across the Atlantic, where Yoruba drummers beat rhythms inherited from centuries past, and where young Nigerians fresh from London universities returned with jazz records under their arms.

By 1960, Nigeria had gained independence, but Lagos was still living with the anxieties of a colonial hangover. The streets bustled with energy yet bristled with uncertainty. Oil revenues were beginning to flow, reshaping the economic landscape, but the country was politically unstable, wracked by coups, counter-coups, and eventually civil war. Amid that turbulence, Lagos emerged as the nerve center of not just politics, but culture—a city searching for a soundtrack that could capture its chaos and hope.

Highlife music, the dominant genre at the time, provided elegance and escapism. It was refined, with brass sections echoing colonial ballroom traditions. Musicians like Rex Lawson, Bobby Benson, and Victor Olaiya entertained the middle class and political elites, but their polished harmonies increasingly felt out of step with the raw restlessness of the younger generation. The city’s youth were no longer content with the genteel rhythms of their parents; they wanted something sharper, angrier, more unfiltered.

The soil was fertile, waiting for a new sound. And into that soil walked a restless figure: Fela Ransome-Kuti.

The Nightclub as a Crucible

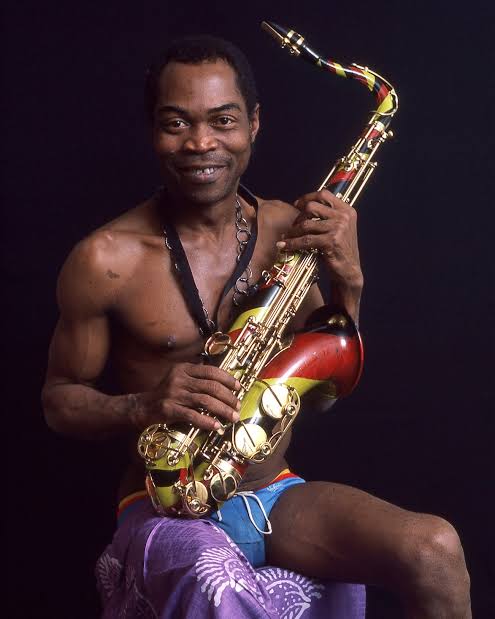

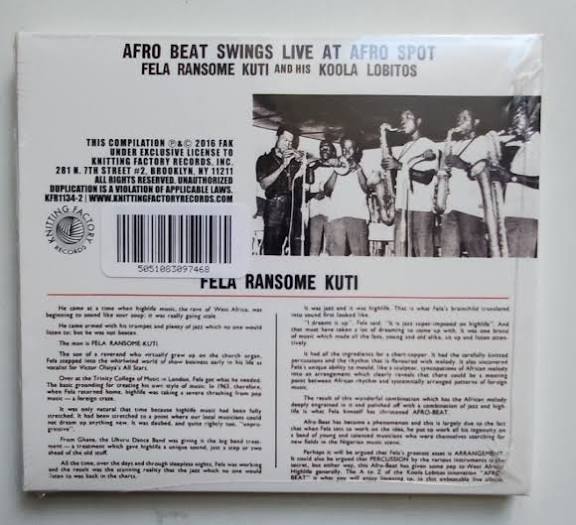

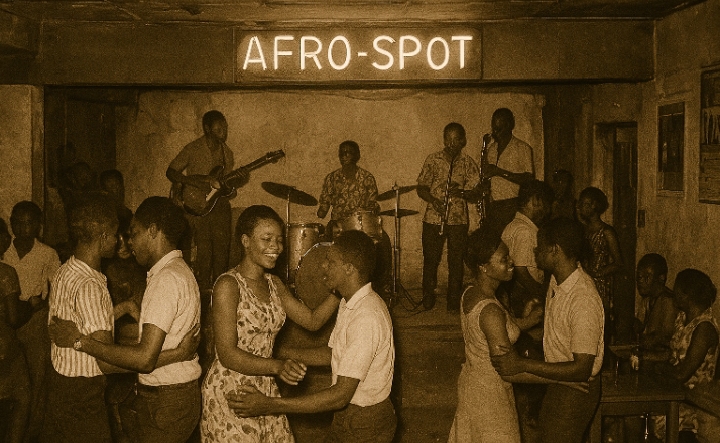

Contrary to popular memory, Afrobeat did not explode fully formed onto the world stage. It was nurtured in cramped, smoky, and chaotic spaces—nightclubs that functioned as laboratories for cultural experimentation. And in Lagos, none was more significant than the Afro-Spot, later renamed the Afro-Club, tucked away in the Surulere neighborhood.

The Afro-Spot was not glamorous. Its wooden floors creaked under the weight of dancers, its ceiling fans often failed against the humid Lagos nights, and its stage lights sometimes dimmed in the middle of a set. Yet it drew a crowd unlike any other venue. On any given night, you might find university students still carrying their textbooks, radical activists debating in whispers, prostitutes leaning against the bar, foreign journalists curious about Nigeria’s new independence, and expatriates hungry for exotic nightlife.

This was not just a club; it was a meeting point of the restless and the marginal. In its heat and sweat, new alliances formed, and new rhythms emerged. Afrobeat was not conceived in a studio—it was born in the improvisational chaos of nights when Fela’s band, then called Koola Lobitos, pushed beyond the safe boundaries of highlife into something jagged, unpredictable, and utterly magnetic.

The Afro-Spot became, in a sense, Lagos itself in miniature: unruly, diverse, volatile, but brimming with life. Its walls absorbed not only the sound of horns and drums, but the political murmurs of a society on the brink of transformation.

The Nightclub as a Crucible

Contrary to popular memory, Afrobeat did not explode fully formed onto the world stage. It was nurtured in cramped, smoky, and chaotic spaces—nightclubs that functioned as laboratories for cultural experimentation. And in Lagos, none was more significant than the Afro-Spot, later renamed the Afro-Club, tucked away in the Surulere neighborhood.

The Afro-Spot was not glamorous. Its wooden floors creaked under the weight of dancers, its ceiling fans often failed against the humid Lagos nights, and its stage lights sometimes dimmed in the middle of a set. Yet it drew a crowd unlike any other venue. On any given night, you might find university students still carrying their textbooks, radical activists debating in whispers, prostitutes leaning against the bar, foreign journalists curious about Nigeria’s new independence, and expatriates hungry for exotic nightlife.

This was not just a club; it was a meeting point of the restless and the marginal. In its heat and sweat, new alliances formed, and new rhythms emerged. Afrobeat was not conceived in a studio—it was born in the improvisational chaos of nights when Fela’s band, then called Koola Lobitos, pushed beyond the safe boundaries of highlife into something jagged, unpredictable, and utterly magnetic.

The Afro-Spot became, in a sense, Lagos itself in miniature: unruly, diverse, volatile, but brimming with life. Its walls absorbed not only the sound of horns and drums, but the political murmurs of a society on the brink of transformation.

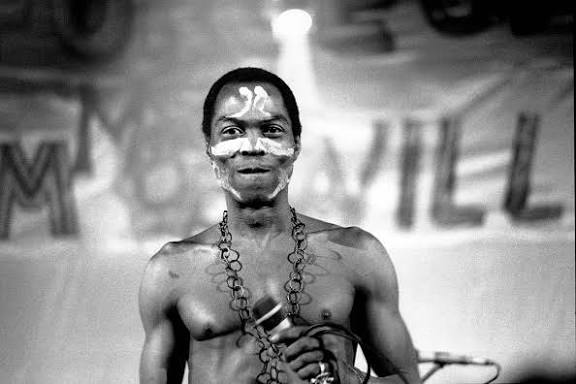

Fela’s Restlessness

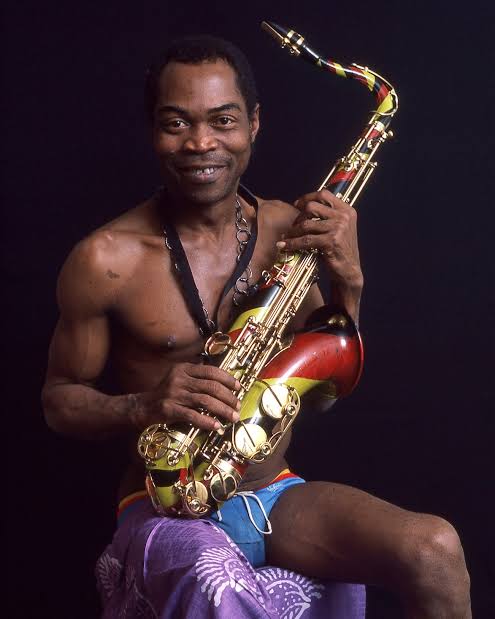

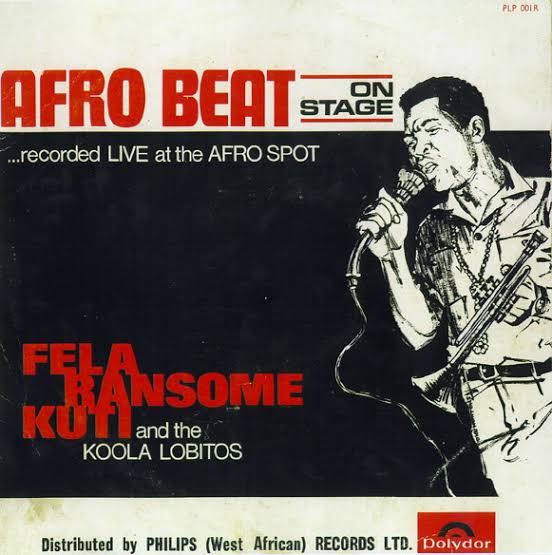

Fela Anikulapo Kuti—then still Fela Ransome-Kuti—was already known as a gifted musician. Born into a prominent Yoruba family in 1938, he was the son of Reverend Israel Oludotun Ransome-Kuti and the fiery feminist activist Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti. His upbringing was steeped in both Western education and radical politics. Music, for him, was never going to be mere entertainment; it was destined to become a vehicle of protest, a language of resistance.

In the late 1950s, Fela left Nigeria to study at the Trinity College of Music in London. There he was exposed to jazz, particularly the music of Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, and Charlie Parker. Jazz’s improvisational freedom and its roots in Black struggle resonated deeply with him. He formed a band, the Koola Lobitos, and began experimenting with blends of highlife and jazz. But it wasn’t until his return to Lagos in the early 1960s that he began to sense that a truly Nigerian sound was waiting to be born.

The Afro-Spot gave him the canvas to experiment. Night after night, he pushed his band into deeper grooves, extending songs far beyond the three-minute radio-friendly format, letting horns riff endlessly over hypnotic drum patterns. His music began to sound less like highlife and more like a dialogue between Africa and its diaspora, between Yoruba rhythms and African-American funk, between tradition and rebellion.

And the Lagos crowd loved it.

The Afro-Spot’s Nights of Fire

To walk into the Afro-Spot in its prime was to step into a sensory storm. The wooden tables were sticky with spilled Star beer. Cigarette smoke curled thickly into the air, mixing with the pungent aroma of fried suya sold outside the entrance. The club’s walls were lined with peeling posters announcing upcoming gigs, and its floor vibrated with anticipation long before the band took the stage.

When Fela and the Koola Lobitos began to play, time seemed to dissolve. The music was relentless, refusing to stop after a neatly packaged verse or chorus. Instead, it expanded like the Lagos night itself, stretching into hypnotic cycles of rhythm. Drummers pounded in intricate Yoruba polyrhythms, guitars scratched out riffs borrowed from American funk, while horns layered brash and urgent melodies over the top.

The audience didn’t just listen—they participated. They shouted, clapped, whistled, and sometimes stormed the stage in excitement. In those moments, the line between performer and audience blurred. Afrobeat was not a product to be consumed; it was a communal experience, an atmosphere, a fever.

Journalists who stumbled into the Afro-Spot during those nights often struggled to describe what they had heard. It was not simply music; it was movement, attitude, and defiance woven into sound. And though the world had yet to hear of Afrobeat, Lagos knew it was witnessing something radical.

Seeds of Rebellion

Afrobeat’s birth in the Afro-Spot coincided with a turbulent moment in Nigerian history. The 1966 coups had shattered the optimism of independence, and by 1967, the Biafran War had engulfed the nation in bloodshed. Lagos, though geographically distant from the frontlines, was not untouched. The city was filled with soldiers, curfews, shortages, and the constant anxiety of a country at war with itself.

Fela’s Afro-Spot sets reflected that turbulence. His lyrics, still relatively cautious at this early stage, began to hint at dissatisfaction with authority. He sang in pidgin English, deliberately choosing the language of the masses over the colonial English of the elite. This linguistic choice alone was a rebellion: Afrobeat was meant to be understood by the market woman and the taxi driver, not just the university graduate.

The Afro-Spot became a kind of underground parliament where Lagosians confronted their disillusionment with Nigeria’s post-independence leaders. Night after night, the music gave voice to unspoken frustrations. In a city where political speech could get one arrested, Afrobeat provided a safer, if still risky, form of expression.

Across the Atlantic: America’s Echoes in Lagos

In 1969, just as the Afro-Spot was solidifying its reputation, Fela took his band to the United States for what was supposed to be a short tour. The journey would change him forever. America was in flames—literally and figuratively. The Vietnam War was raging, Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated, Malcolm X before him, and the Black Panther Party was challenging the American establishment.

It was in Los Angeles that Fela encountered Sandra Izsadore, a young African-American activist deeply involved in the Black Power movement. She opened his eyes to the writings of figures like Eldridge Cleaver, Angela Davis, and Malcolm X, and introduced him to a political vocabulary he had never fully encountered before. For Fela, who had grown up in the shadow of his mother’s fiery activism in Nigeria, this was like a missing puzzle piece falling into place.

Sandra convinced him that his music should not just entertain—it should liberate. That realization forever altered the course of Afrobeat. Fela returned to Lagos a changed man, determined to use his music not just as rhythm but as weapon.

When he resumed playing at the Afro-Spot after his return, Lagosians immediately sensed the difference. The grooves were deeper, the lyrics sharper, the attitude bolder. Afrobeat had gone from being an exciting fusion of sounds to being an unapologetic declaration of identity and resistance.

The Afro-Spot Transforms into the Shrine

The Afro-Spot, by the early 1970s, had already become the unofficial headquarters of this new movement. But Fela’s ambitions soon outgrew it. The venue was small, and police harassment was constant. The authorities viewed the club not as a place of music but as a breeding ground for dissent. Soldiers in uniform sometimes stood outside, monitoring who went in and out.

In 1970, Fela established the Kalakuta Republic—a communal compound that served as both his residence and a hub for his band members, dancers, and followers. Alongside it, he created a new performance space: the Afrika Shrine. The Shrine, unlike the Afro-Spot, was explicitly political. Its walls were covered with posters of African freedom fighters. Speeches and sermons were delivered between songs. Marijuana smoke drifted freely through the air, defying Nigeria’s laws.

Yet, the Afro-Spot remained the symbolic birthplace. Without it, there could have been no Shrine. The Afro-Spot was the testing ground, the womb where the embryo of Afrobeat had first taken shape before maturing into the full-bodied defiance of the Shrine.

Lagos as a Character in the Story

It would be a mistake to see Afrobeat’s birth as the work of one man alone. Lagos itself was as much a co-creator as Fela. The city in the late 1960s was loud, volatile, and unrelenting. It had the energy of a restless teenager—unpredictable, prone to sudden violence, yet bursting with creative life.

Markets like Balogun and Idumota throbbed with Yoruba, Igbo, and Hausa voices, as traders shouted prices above the blare of imported transistor radios. Danfo drivers swerved recklessly through streets that colonial planners had never designed for such chaos. Soldiers barked orders at checkpoints, while university students protested corruption in the universities. Lagos was a city where the lines between survival and celebration blurred every single day.

The Afro-Spot captured that spirit. In its music, you could hear the honk of danfos, the cry of street hawkers, the call of Yoruba drummers, the swagger of funk, and the improvisation of jazz. It wasn’t just entertainment—it was Lagos in sound.

The Afro-Spot and Its Patrons

Every nightclub has its legends, and the Afro-Spot was no exception. Stories circulate of nights when Fela would play until dawn, sweat pouring down his bare chest as he screamed into the microphone, refusing to let the music stop. On those nights, patrons left not just entertained but transformed, convinced they had witnessed something revolutionary.

The crowd was eclectic. University radicals from the University of Lagos came in groups, debating politics at the tables. European expatriates—diplomats, businessmen, journalists—came seeking “exotic” thrills, though many left unsettled by the raw defiance in the music. Prostitutes made the Afro-Spot their hunting ground, while working-class Lagosians, having survived grueling days, spent their last kobo on beer just to feel part of the fever.

It was in these mixed crowds that Afrobeat found its first disciples. The genre’s insistence on being both accessible (through pidgin English lyrics) and sophisticated (through complex jazz arrangements) meant it could speak across class divides. Few other Nigerian nightclubs could boast such an audience.

Government Suspicion and Crackdowns

As Afrobeat grew bolder, the Nigerian state grew more suspicious. Military regimes in the 1970s were notoriously intolerant of dissent, and Fela quickly emerged as a thorn in their side. Though the Afro-Spot had birthed Afrobeat, by the time the Shrine became central, the authorities already saw Fela as a threat.

But the seeds of that hostility were planted during the Afro-Spot years. Police regularly raided the club, often citing “noise complaints” or “drug suspicions.” Musicians were beaten, instruments confiscated. At times, electricity was cut mid-performance, plunging the club into darkness. Yet, each time, the music returned, more defiant than before.

The Afro-Spot, in its later years, became a place of both celebration and danger. To attend was to risk harassment, but also to experience a kind of freedom that Lagos rarely offered. Afrobeat was not just sound—it was defiance set to rhythm.

Memory of a Place

Every great movement has a birthplace, and for Afrobeat, it was not a parliament chamber, nor a university lecture hall, nor even the stages of Europe—it was a modest Lagos nightclub whose very existence was precarious. Today, the Afro-Spot no longer stands in its original form. Lagos has a way of erasing its past quickly, replacing it with the steel and glass of new ambitions. Yet, in the oral histories of musicians, dancers, and patrons who lived through its nights, the Afro-Spot remains vivid.

Ask an aging saxophonist who once played in its band pit, and he will describe the sweat dripping down his shirt as the crowd demanded one more solo. Ask a woman who used to sell pepper soup outside its entrance, and she will recall the endless stream of dancers who spilled out onto the street when the club became too hot inside. For them, the Afro-Spot was not just a building but a crossroads—a meeting place of politics, culture, and survival.

In a city like Lagos, where memories are often drowned out by the noise of constant change, the Afro-Spot lives on precisely because it was more than entertainment. It was resistance dressed in rhythm.

The Nightclub as University

For Fela, the Afro-Spot was more than a performance venue—it was a classroom. Each night, he learned what Lagos wanted to hear, what rhythms could move bodies, what lyrics made people nod in recognition. Unlike the formal training he had received at Trinity College in London, this was education from the street, raw and unfiltered.

Songs were tested in real time. If a groove fell flat, the audience’s silence was deafening. If it hit, the response was volcanic—cheers, claps, whistles, and sometimes full-on dancing on stage. Afrobeat was thus not invented in isolation but co-created with the crowd. The Afro-Spot’s audience shaped the music as much as the musicians did.

This is why Afrobeat carried such urgency. It was not composed for elite critics but for everyday Lagosians who lived with inflation, police harassment, and the grind of survival. The Afro-Spot was their university too—where music became a form of civic education, teaching them to question, to resist, to dream.

The Afro-Spot’s Sonic Legacy

Though the club itself eventually faded, its sound never did. From the Afro-Spot stage emerged the signature elements that defined Afrobeat for decades:

- Extended grooves that stretched songs to 20 or even 30 minutes.

- Call-and-response vocals, rooted in Yoruba tradition, giving audiences a role in performance.

- Horn sections blasting political urgency.

- Rhythm sections that married West African drumming with funk’s heartbeat.

- Lyrics in pidgin English, ensuring accessibility across Nigeria’s ethnic spectrum.

Those choices—tested and perfected in Afro-Spot’s sweaty nights—are what allowed Afrobeat to leap continents. Even when Fela later performed in London, Berlin, or New York, he carried the Afro-Spot with him. Each stage became an echo of that first Lagos nightclub.

Global Expansion Without Borders

By the late 1970s, Afrobeat had crossed oceans. Fela’s collaborations with British drummer Ginger Baker drew international attention. Musicians from James Brown to Paul McCartney visited Lagos, intrigued by the city’s sound. Nigerian records began circulating in London’s underground clubs, and by the 1980s, Afrobeat had become a global reference point for Black diasporic music.

But global audiences often missed the Afro-Spot story. They encountered Afrobeat in polished form—through long-playing records or festival stages—without knowing the cramped Lagos nightclub where it had been forged. To them, it was a new genre of world music. To Lagosians, it was memory, sweat, survival, and politics distilled into sound.

The Afterlife of Afro-Spot in Lagos Nightlife

Lagos has never stopped producing nightclubs, but each new venue carries echoes of the Afro-Spot. The New Afrika Shrine, run today by Fela’s children, continues the tradition, blending music with activism. Clubs in Victoria Island, Surulere, and Lekki, though glossier and more commercial, still borrow the Afro-Spot ethos: music as a communal experience, not just background noise.

Young Nigerian artists—Seun Kuti, Femi Kuti, Burna Boy, Wizkid—draw direct or indirect inspiration from Afrobeat’s origins. Burna Boy’s Grammy-winning “Twice as Tall” album owes much to Afrobeat’s structure: layered rhythms, political undertones, and unapologetic African identity. Without Afro-Spot, that lineage would be broken.

Even Lagos’s contemporary nightlife culture, from Afro-house parties to underground hip-hop sessions, carries the DNA of Afro-Spot: the idea that music can be a gathering of resistance, not just consumption.

The Symbolic Power of a Small Place

What makes the Afro-Spot remarkable is that it was small. It had no grand architecture, no international investors, no glittering chandeliers. It was not designed to be a landmark. Yet, like Harlem’s Cotton Club or Havana’s Tropicana, it became legendary because of what was created inside it.

In Nigeria’s cultural memory, the Afro-Spot symbolizes possibility. It reminds us that revolutionary ideas rarely begin in palaces or parliaments—they are born in ordinary spaces where ordinary people gather, argue, dance, and dream. The Afro-Spot was one of those places: a modest nightclub that changed the sound of a continent.

Legacy Beyond Music

Afrobeat’s legacy is not just sonic but cultural. The Afro-Spot years taught Nigerians that identity could be reclaimed through creativity. In an era when colonial residues still shaped education, law, and governance, Afrobeat offered something different: an unapologetically African modernity.

This legacy endures. Today, when Nigerian artists dominate global charts, their confidence comes from a lineage that began in spaces like the Afro-Spot. The nightclub’s story is not nostalgia—it is foundation.

Parting Words: The Beat Goes On

The Afro-Spot may have vanished physically, but it survives in memory, influence, and rhythm. It lives in the way Lagos still throbs at night, in the way Afrobeat still commands festival stages across continents, and in the way Nigerian music refuses to be anything but global.

When Lagosians look back at that small, smoky club in Surulere, they see more than a stage. They see the birthplace of a genre that would carry their city’s chaos, resilience, and defiance across the world. Afrobeat was born in a nightclub, but it refused to stay there. Its beat, once confined to the Afro-Spot, now belongs to the world.

And so, each time a bassline thunders in a Lagos club today, or a saxophone wails in a Brooklyn concert hall, or a crowd chants to Burna Boy in London, the ghost of the Afro-Spot is there—reminding us that the rhythm of resistance was born in Lagos, and it never stopped playing.