In the teeming streets of South-west Nigeria, where every corner hums with the rhythm of life, there exists a sound that is both familiar and transformative. It is a pulse that seems to echo the heartbeat of the city itself—a percussion that commands attention, stirs emotion, and defies time. Those who have witnessed a King Wasiu Ayinde Marshal performance know that Fuji music is not merely entertainment. It is a living dialogue between tradition and innovation, a conversation between drummer and dancer, musician and audience.

- The Genesis of Fuji: Roots and Evolution

- The Anatomy of Percussion in Fuji

- A. Traditional Instruments of Fuji

- B. Percussion as Language

- C. Structure of a Fuji Percussion Ensemble

- D. Rhythm and Emotional Impact

- King Wasiu Ayinde Marshal’s Percussive Mastery

- A. Early Influences and Training

- B. Innovations in Percussion Techniques

- C. Signature Sound and Style

- D. Mastery as Cultural Preservation

- E. International Recognition and Influence

- Hit Songs in Focus

- The Cultural Impact of His Percussion

- The Future of Fuji Percussion

- The Eternal Rhythm

But what is it about the man known as K1 De Ultimate that elevates percussion from mere beats to an almost spiritual experience? What unseen mastery allows a cluster of drums to speak, to narrate tales of Yoruba streets, markets, mosques, and celebrations? And how has a genre that began as were music for Ramadan prayers evolved into a global emblem of Nigerian identity, largely under his hands?

This article is not a recounting of songs or setlists. It is an exploration—a journey into the heartbeat of Fuji percussion, the subtle genius of its modern master, and the historical forces that shaped him. Through meticulous research, historical accounts, and analysis of musical technique, we peel back layers of rhythm, revealing the artistry and the intellect behind every drumbeat.

By the end, readers will not only understand King Wasiu Ayinde’s contribution to music but also gain insight into how percussion in Fuji has become a language, a cultural chronicle, and a beacon of Yoruba heritage.

The Genesis of Fuji: Roots and Evolution

A. Origins in Yoruba Tradition

Before Fuji became a household name, it existed in a quieter, sacred form known as were music. Rooted in Yoruba Islamic traditions, were was performed to wake the faithful during Ramadan for pre-dawn prayers. The rhythms were simple yet hypnotic, often consisting of hand claps, basic drum patterns, and vocal chants. These performances were more than music; they were communal rituals, a way to synchronize the city’s spiritual pulse.

Young performers, often boys from local communities, learned to replicate the vocal and percussive patterns, creating improvisational dialogues between drums and chants. It is from this fertile cultural soil that Fuji would eventually sprout—a genre that would carry the essence of Yoruba rhythm into the urban spaces of Lagos and beyond.

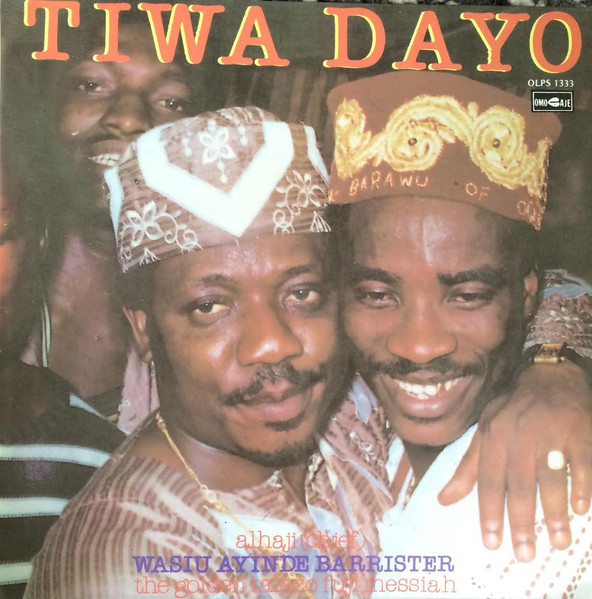

B. The Sikiru Ayinde Barrister Influence

The 1960s and 70s marked a turning point. Sikiru Ayinde Barrister, widely regarded as the father of modern Fuji, transformed were music into a vibrant, socially conscious art form. Barrister introduced a variety of new percussion instruments—sakara, bata, and talking drums—creating layered textures previously unseen in Yoruba musical traditions.

Barrister’s genius was in synthesizing the old with the new. He maintained the ritualistic core of were while infusing it with contemporary themes, humor, and urban storytelling. This hybrid form resonated across Lagos, bridging the gap between mosque courtyards and city nightclubs. For the first time, percussion in this style was not just rhythm; it was narrative. It could convey tension, joy, and social critique with subtle nuance.

C. King Wasiu Ayinde Marshal Emerges

Born in Lagos in 1957, Wasiu Ayinde Marshal entered a world steeped in music. His early life was punctuated by the percussive sounds of local ceremonies, street performers, and the rising tide of Fuji under Barrister’s leadership. Unlike many young musicians who simply imitated their mentors, Wasiu absorbed the rhythm, internalized it, and began experimenting with its possibilities.

By the late 1970s, he was performing alongside Barrister, learning the intricacies of drum placement, rhythm layering, and audience engagement. But unlike his contemporaries, Wasiu began pushing boundaries—exploring polyrhythms, integrating foreign percussion techniques, and eventually creating a signature style that would become synonymous with modern Fuji.

His emergence was not instantaneous; it was a patient accumulation of experience, experimentation, and cultural literacy. By mastering the foundations laid by Barrister, he set the stage for a revolution in percussion—one that would make Fuji not just music but a living language of Yoruba identity.

The Anatomy of Percussion in Fuji

Fuji music is not merely a collection of beats; it is a language—a sonic conversation between musician and audience. Central to this language is percussion. Every drum, shaker, and bell carries meaning, weaving stories that transcend words. King Wasiu Ayinde Marshal’s mastery lies in his ability to manipulate these instruments, crafting rhythms that feel both familiar and revolutionary.

A. Traditional Instruments of Fuji

1. Talking Drum (Dundun)

The talking drum is arguably the most iconic instrument in Yoruba percussion. Its unique shape allows players to vary pitch by tightening or loosening the drumhead with a curved stick. This capability lets the drum “speak,” imitating Yoruba tonal speech patterns. In Fuji, the talking drum acts as both rhythmic anchor and messenger, punctuating songs with tonal inflections that mimic dialogue, praise, or admonition.

2. Batá Drum

Originating from Yoruba religious ceremonies, the bata drum carries both spiritual and cultural significance. Traditionally used in ritual contexts, the bata was adopted into Fuji to provide deeper resonance and dynamic rhythmic layering. Its rapid-fire sequences and polyrhythms amplify energy, engaging listeners in physical and emotional ways.

3. Sakara Frame Drum

Smaller than the bata, the sakara drum resembles a tambourine and adds texture and syncopation to Fuji ensembles. Its soft, metallic jingles complement the heavier beats of the talking and bata drums, creating a multidimensional percussive landscape.

4. Gangan and Agogo Bells

Supporting the primary drums, smaller instruments like the gangan (small talking drum) and agogo bell punctuate beats and accentuate rhythmic complexity. These instruments create tension, highlight transitions, and emphasize lyrical phrases, showing the depth of Fuji’s percussive vocabulary.

B. Percussion as Language

In Fuji, percussion communicates as much as vocals. Through the interplay of pitch, rhythm, and tempo, drums convey messages of joy, mourning, resistance, or celebration. The audience, familiar with these patterns, interprets them almost intuitively. King Wasiu Ayinde Marshal elevated this principle by:

Polyrhythmic layering: Multiple drum patterns run simultaneously, creating a rich tapestry of sound.

Dynamic tempo shifts: Gradual acceleration or deceleration of rhythm mirrors emotional arcs in lyrics.

Interactive improvisation: Drummers respond to vocal cues, audience energy, or fellow musicians, creating spontaneous dialogue.

This communicative approach turns every performance into a narrative, where percussion functions as storyteller, historian, and mediator between performer and listener.

C. Structure of a Fuji Percussion Ensemble

A typical Fuji ensemble under King Wasiu might include:

- Lead talking drum (signal and narrative)

- Bata drums (main rhythmic body)

- Sakara drum (texture and syncopation)

- Supporting percussion (bells, shakers, and secondary drums)

Each instrument plays a distinct role, but the genius lies in their synchronization. King Wasiu orchestrates these elements like a conductor, guiding the ensemble to shift moods, highlight lyrics, and maintain constant tension and release.

D. Rhythm and Emotional Impact

Fuji percussion is not only cerebral; it is visceral. Polyrhythms, syncopation, and drum call-and-response patterns evoke physical movement, compelling listeners to dance, clap, or gesture along. King Wasiu’s performances are particularly immersive: audiences feel the rhythm, not just hear it. This emotional resonance is a testament to his meticulous understanding of how percussive structure interacts with human perception and cultural familiarity.

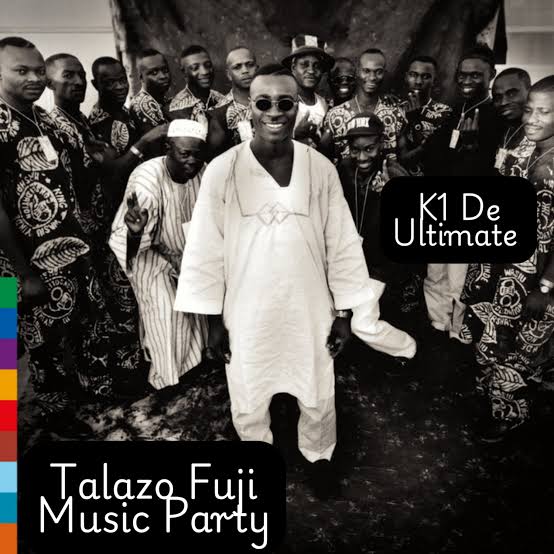

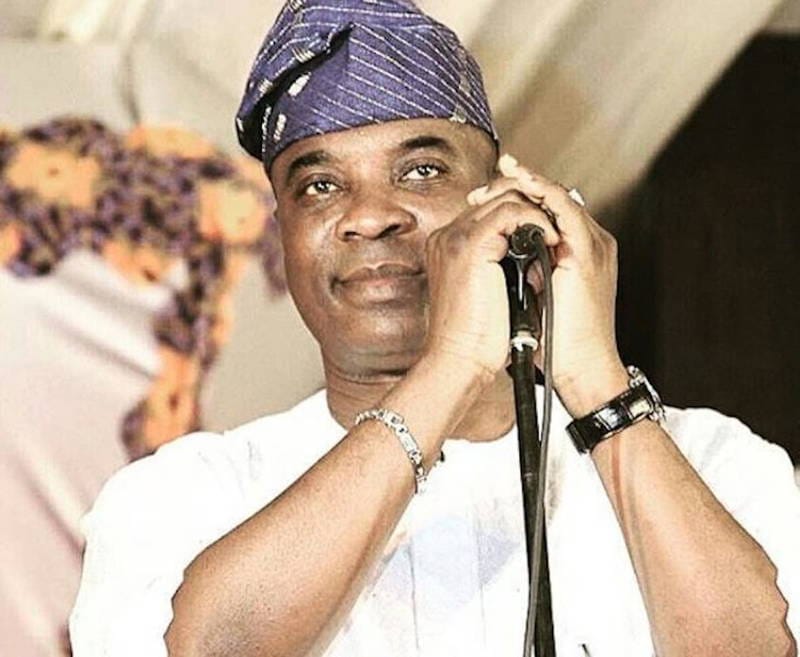

King Wasiu Ayinde Marshal’s Percussive Mastery

King Wasiu Ayinde Marshal, widely known as K1 De Ultimate, is not merely a performer; he is a percussive architect. His genius lies in taking traditional Fuji elements and elevating them into a sophisticated musical language, one that commands both respect and emotional investment from audiences.

A. Early Influences and Training

Wasiu Ayinde’s journey into mastery began in childhood. Growing up in Lagos, he was immersed in the rhythmic landscape of Yoruba music—from the mosque-based were rhythms of Ramadan to the street performances of local drummers.

His apprenticeship under Sikiru Ayinde Barrister provided formal exposure to Fuji’s mechanics, but Wasiu’s innate sensitivity to rhythm allowed him to go further. He would spend hours experimenting with drum placements, layering, and call-and-response sequences, refining his technique until he could anticipate not just the audience’s reactions, but the subtle interplays between multiple percussion instruments.

B. Innovations in Percussion Techniques

King Wasiu’s major contributions to Fuji percussion include:

1. Polyrhythmic Complexity

He introduced intricate layers of simultaneous drum patterns, creating textures previously unseen in Fuji. By blending multiple rhythms in ways that maintain clarity, he allowed audiences to experience both structure and improvisation concurrently.

2. Dynamic Tempo Control

Wasiu is renowned for his ability to manipulate tempo during performances. Gradual accelerations heighten anticipation, while sudden decelerations amplify lyrical emphasis. This gives his music a storytelling dimension, where rhythm becomes a narrative arc.

3. Integration of Global Percussive Elements

Unlike traditionalists, King Wasiu embraced external influences—from Afrobeat syncopation to Latin percussion—infusing Fuji with a cosmopolitan vibrancy. These incorporations broadened Fuji’s appeal without compromising its Yoruba roots.

C. Signature Sound and Style

King Wasiu’s style is instantly recognizable: a seamless fusion of Yoruba rhythmic heritage with innovative percussive arrangements. Signature characteristics include:

- A central talking drum that communicates alongside vocals.

- Layered bata and sakara patterns that provide depth and momentum.

- Improvisational solos that respond to audience energy and lyrical content.

- Use of tension and release, creating emotional peaks in every song.

This approach transforms Fuji from simple entertainment into a multidimensional, participatory experience. Listeners do not just hear the music; they feel it, engage with it, and internalize its cultural messages.

D. Mastery as Cultural Preservation

Beyond technical prowess, King Wasiu’s mastery serves as a cultural safeguard. His meticulous adherence to Yoruba percussion techniques ensures that the traditions of were, bata, and sakara remain vibrant. By blending tradition with innovation, he creates a bridge between past and future, ensuring that young audiences experience Fuji not as an outdated form but as a living, evolving art.

E. International Recognition and Influence

King Wasiu’s influence extends beyond Nigeria. His performances in London, New York, and Atlanta have introduced Fuji percussion to global audiences, inspiring musicians across genres. International observers note his unique ability to translate complex Yoruba rhythms into universally resonant musical narratives.

His mastery demonstrates that percussion is not merely accompaniment—it is storytelling, cultural preservation, and emotional expression, all interwoven into a single, compelling performance.

Hit Songs in Focus

Fuji music is more than a genre; it is a dialogue between rhythm and human emotion. King Wasiu Ayinde Marshal’s percussion mastery comes alive when we examine his iconic tracks, where drums tell stories as vividly as vocals. Take, for example, the song “Talazo Fuji”, widely regarded as a seminal work in his repertoire.

The opening layers of bata drums establish a steady, hypnotic pulse, while the talking drum converses with the lead vocals, punctuating phrases with tonal inflections that mimic Yoruba speech. The sakara adds a subtle, rolling shimmer that contrasts with the heavier beats, creating a sense of forward momentum. By the time the chorus arrives, the drums have woven a narrative of anticipation and release, inviting the listener to move not just physically but emotionally.

In albums like “Fuji The Sound”, King Wasiu experiments with tempo shifts, beginning with a slow, deliberate opening that mirrors the cadence of traditional were music. Gradually, the drums accelerate, layering syncopated bata and sakara patterns, which mirror the lyrical journey from reflection to celebration. The talking drum communicates tonal “phrases,” almost as if translating the lyrics into its own language. Listeners feel the story not only through words but through the intricate, dynamic pulses of the percussion.

Even in songs like “Let The Music Flow Vol. 2”, which some critics regard as a modern reimagining of classic Fuji, the percussion is masterful in its complexity. Here, the talking drum initiates call-and-response sequences, while the bata drums maintain a relentless polyrhythmic structure beneath.

Subtle tambourine-like accents punctuate moments of lyrical climax, creating a rhythmically immersive environment. Each percussion element interacts with the others, producing an intricate web of sound that is simultaneously grounded and improvisational.

Through these songs, King Wasiu demonstrates that Fuji percussion is more than background—it is narrative, commentary, and emotion rendered in sound. His drum arrangements are not merely technical feats; they are storytelling devices that convey Yoruba culture, social nuances, and communal energy.

The Cultural Impact of His Percussion

King Wasiu Ayinde Marshal’s influence reshaped not only Fuji music but the entire Nigerian musical landscape. Contemporary artists across genres—Afrobeats, gospel, and hip-hop—have incorporated his rhythmic structures, polyrhythms, and call-and-response techniques into their own work. His live performances, known for interactive drumming that responds to audience energy, became a blueprint for engagement, inspiring performers to rethink the relationship between rhythm and listener.

Fuji percussion under King Wasiu also serves as a repository of Yoruba heritage. Through careful attention to instruments, rhythmic phrasing, and traditional structures, his music preserves the essence of were, bata, and sakara rhythms. Lyrics and drum phrases carry cultural narratives, educating audiences on Yoruba history, values, and social norms. Even as globalization introduces new musical trends, King Wasiu ensures that Fuji remains a cultural anchor, bridging past and present.

Internationally, his work elevated Fuji to a global platform. Concerts in Europe and North America introduced audiences to Yoruba percussive complexity, inspiring cross-cultural collaborations and global appreciation. His rhythms became not just music but a form of cultural diplomacy, showing that tradition and innovation can coexist. Perhaps most significantly, his mastery inspires younger musicians. Drummers study his techniques, aspiring performers emulate his improvisational style, and his methods have become part of music curricula, ensuring that Fuji percussion evolves while remaining rooted in Yoruba tradition.

The Future of Fuji Percussion

The future of Fuji percussion is inseparable from King Wasiu Ayinde Marshal’s legacy. Young drummers now study his intricate polyrhythms and dynamic tempo techniques, using them as a foundation to innovate further. Music schools incorporate his methods into formal curricula, while apprentices in Lagos continue the traditional mentorship approach, learning the art directly from masters or recordings of his performances.

Technology also amplifies his influence. Modern recording techniques capture the full complexity of Fuji percussion, and online platforms expose global audiences to rhythms once confined to Nigerian stages. Contemporary artists integrate these patterns into Afrobeats, gospel, and electronic music, spreading Fuji’s influence across genres while inspiring interactive performance techniques that encourage audience engagement.

King Wasiu’s vision emphasizes balance—innovation must honor tradition. Elements of were and ceremonial percussion continue to inform new compositions, ensuring that cultural memory survives even as the genre evolves. By preserving ritualistic rhythms while embracing global influences, he has future-proofed Fuji, allowing it to resonate with audiences worldwide without losing its identity. The next generation of musicians inherits a living tradition, one in which rhythm is simultaneously entertainment, storytelling, and cultural preservation.

The Eternal Rhythm

In the panorama of Nigerian music, few figures command the reverence accorded to King Wasiu Ayinde Marshal. From the humble roots of were music to commanding international stages, he has transformed Fuji percussion into a sophisticated, living art form. Every drumbeat, every rhythmic nuance in his performances carries history, emotion, and intellect. Fuji percussion, under his guidance, has become a language, a vessel of Yoruba heritage, and a bridge connecting generations.

King Wasiu’s genius lies not only in technique but in his understanding of music as a living entity. He innovates without severing tradition, creating rhythms that are both contemporary and timeless. His polyrhythms, call-and-response patterns, and dynamic tempo shifts transform performances into narratives, engaging audiences in ways that transcend words.

As Fuji percussion continues to evolve, King Wasiu’s influence remains foundational. His mentorship, recordings, and international performances ensure that young musicians have both a model and a roadmap. In a world of fleeting musical trends, some rhythms endure. King Wasiu Ayinde Marshal’s percussion is one such rhythm—an eternal pulse that continues to inspire, educate, and preserve the cultural heartbeat of the Yoruba people.