Night in Lagos is a theatre that never sleeps, but on some evenings, it sharpens into something more than noise. It becomes expectation.

- Bukola Elemide: From Paris Birth to Lagos Childhood

- The First Notes That Echoed Through Lagos Nights

- The Album That Spoke in Two Languages

- “Jailer”: A Song of Chains, Sung on Two Continents

- “Fire on the Mountain”: Prophecy in Melody

- “Bibanke”: The Grief That Spoke in Yoruba

- “Eye Adaba”: The Dove That Carried Hope

- “360 Degrees” and “No One Knows”: The Circle of Uncertainty

- How Asa Changed the Sound of Lagos Forever

- Beautiful Imperfection: When Asa Painted with New Colors

- Bed of Stone: Asa’s Descent into Depth

- Lucid: The Return of Light After Shadows

- When Asa Opened the Door to a New Generation

- Legacy of a City in a Voice

- Why Paris Couldn’t Hold Her

- A Legacy Written in Two Languages

- The Eternity She Sang Into

- A Lasting Thought: Lagos as Asa’s Eternal Stage

That night was one of them.

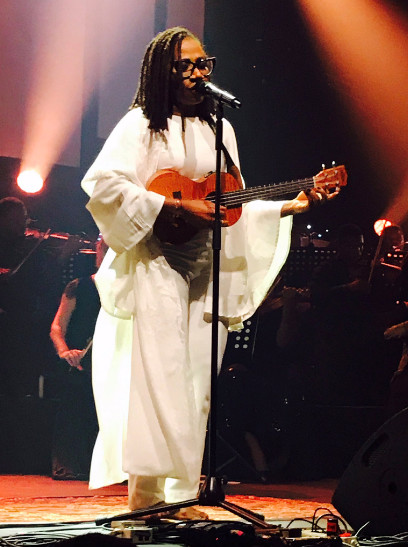

Long before the stage lights warmed, the air was already heavy. People were pressing in—bankers still in rolled-up sleeves, students clutching tickets like they were currency against forgetting, and elders who had come with memories of old highlife nights in Surulere. The crowd was not merely here for music; Lagos crowds rarely are. They had come for confirmation—proof that the voice they had been whispering about was not a dream carried from France, but flesh and breath born of their city’s soil.

Somewhere backstage, she was waiting. A woman whose name carried both distance and nearness, whose very identity had been split by geography. Bukola Elemide—Aṣa to the world.

Her guitar was already tuned, the wood dark and unassuming under the low light. Her band shifted in nervous half-silence, waiting for the cue that would turn background into foreground. She did not speak much before concerts. She preferred instead to listen—to the room, to the vibrations that floated from crowd to ceiling, to the city that always seemed to breathe louder just before she sang.

And Lagos was breathing.

There is a silence Lagos keeps only for its chosen voices. Once, it was reserved for Fela’s trumpet on a smoky stage at The Shrine, or Ebenezer Obey’s guitar echoing across wedding halls on the Island. Now, for one evening, that silence belonged to Asa.

She adjusted her scarf, tightened her grip on the guitar, and waited.

What the audience did not know yet was that her presence on this Lagos stage had not been inevitable. Paris could have claimed her. Paris, with its jazz clubs and recording labels, with its boulevards that had first whispered to her as a child born there. Paris had made her comfortable, had offered her polish. But Lagos, for all its chaos and exhaust, offered something different—an intimacy, an urgency, a mirror.

What happened that night was not just a concert, not just a performance. It was a decision, though no one would recognize it as such until much later. It was the night Aṣa refused Paris—not in anger, not in exile, but in a quiet insistence that her music belonged first to the streets that shaped her, the chaos that bruised her, the laughter that healed her. It was the night she chose Lagos, and in doing so, she wrote herself into the eternity of Nigerian sound.

But eternity is never born in a single night. To understand why this mattered, one must go back—to the twin geographies that defined Asa’s life, the tug-of-war between the cold order of Europe and the fevered pulse of Nigeria.

Bukola Elemide: From Paris Birth to Lagos Childhood

Every great voice begins before the first song.

For Aṣa, that beginning was not in Lagos, though Lagos would later insist on being her home. She was born Bukola Elemide on September 17, 1982, in Paris, to Nigerian parents who had traveled abroad in search of work. Her father, a cinematographer, filled their home with records—classic soul, reggae, and highlife—and her mother kept the household grounded in Yoruba tradition. In Paris, the child who would one day be Asa inhaled melodies before she could even spell her name.

But childhood is rarely straightforward. Before long, her parents returned to Nigeria, and Bukola’s earliest memories of identity were not Parisian boulevards but Lagos streets—dusty roads humming with hawkers, music spilling out of shops, neighbors calling through thin walls. Lagos was where she grew up, attended school, and discovered her relationship with sound.

In her father’s collection, she found the voices that would shape her own. Marvin Gaye. Fela Kuti. Bob Marley. Aretha Franklin. Ebenezer Obey. They were not just records but teachers, each one a lesson in tone, in courage, in storytelling. Young Bukola would slip into quiet corners with her guitar, trying to find where her own sound fit between them.

But Lagos was not always forgiving. The city loved its pop stars—its Fuji kings, its Afrobeat generals, its crooners who could fill dancefloors. A girl with a guitar, soft-spoken, writing lyrics about loneliness and light, seemed out of place. She was not chasing noise; she was chasing resonance. And in Lagos, resonance had to fight to be heard.

There were times she almost gave up. She carried her guitar to auditions, sang in small clubs, and was met with blank stares from promoters who wanted faster beats and brighter clothes. Yet Asa persisted, her Yoruba name—“Asa,” meaning Hawk—turning into prophecy. She soared above rejection, circling patiently until the right moment arrived.

That moment was Paris again.

By the early 2000s, Aṣa returned to the city of her birth, this time not as a child but as an artist in waiting. Paris welcomed her like an old friend—it gave her structure, industry, and a path into the global music scene. She enrolled at the IMFP (Institut Musical de Formation Professionnelle), refining her craft, sharpening the edges of her folk-soul style. French producers noticed. Labels leaned in. A debut album was on the horizon.

In the small Parisian clubs where she began to perform, her songs floated into air that seemed designed for them. Acoustic ballads were not strange in Paris—they were expected, even revered. The audience leaned in with a quiet intensity unfamiliar to someone raised in Lagos’ restless halls. Here, her voice did not need to fight against the city’s noise; it could unfold in silence.

Paris wanted her.

Soon, industry figures noticed. She signed with Naïve Records, a French independent label, and began recording what would become her self-titled debut album, Asa (2007). With producer Cobhams Asuquo as her longtime collaborator, she built a sound that combined Parisian polish with Lagos rawness, balancing Western instrumentation with African soul.

The world was ready. When the album dropped, it traveled far. Songs like Jailer became anthems not only in Nigeria but across Europe. Fire on the Mountain played in cafés in Paris as easily as in bus stations in Ibadan. Critics praised the maturity of her lyrics, the way her songs confronted injustice without losing their melodic tenderness. Awards followed. Asa was named the winner of the Prix Constantin in 2008, marking her as a force not just in Africa but on the global stage.

But if Paris offered her a stage, Lagos continued to demand her soul.

Because something about performing in Paris, for all its applause, carried a shadow of distance. The audience understood her lyrics, yes, but not always the weight of their context. A song like Bibanke—sung partly in Yoruba—was beautiful to French ears but deeply familiar to Nigerian ones. Jailer could be heard as a universal critique of oppression in Europe, but in Lagos it echoed lived realities of corruption and police brutality.

And so Aṣa found herself at a crossroads. She could remain in Paris, crafting a neat identity as a global soul-folk singer, touring Europe, praised but never fully claimed. Or she could return to Lagos, to the noise and chaos, to the city that had once doubted her but would ultimately call her its own.

It was not an easy choice. Paris was safe. Lagos was unpredictable. Paris meant consistency. Lagos meant risk. But Asa was never built for safety.

So when the time came to anchor her music in performance, she did not choose the City of Light. She chose the city of neon markets, broken streets, and relentless rhythm. She chose Lagos.

And in doing so, she refused Paris—not as rejection, but as redirection. She refused to be only Paris’ voice when Lagos had given her one in the first place.

The First Notes That Echoed Through Lagos Nights

When Asa carried her songs back to Lagos, she was not just returning home. She was testing the city. Would Lagos, in all its impatience, accept her stripped-down honesty? Would it understand the quiet ache in Bibanke, the political fire in Jailer, the haunting lament of Fire on the Mountain?

Her first major concerts on Nigerian soil answered with thunder.

At the Convention Centre of Eko Hotel and Suites, Lagosians gathered in numbers that startled even the organizers. Some came with skepticism—could this Paris-returned artist with an acoustic guitar really hold a Lagos crowd? But as the lights dimmed and Asa stepped into the spotlight, the question dissolved into silence.

She did not need spectacle. No fireworks, no dancers, no distracting theatrics. Just a guitar, a band that trusted her pauses as much as her chords, and a voice that carried weight.

The opening song was Jailer. A single strum and the hall erupted, the audience already singing along before she reached the chorus. What Paris had heard as a general protest against oppression, Lagos heard as a direct commentary on their daily struggles—unjust arrests, political corruption, a system that often jailed the innocent while freeing the guilty. The words landed differently here, sharper, heavier, personal.

Then came Fire on the Mountain. The guitar rang out with eerie calm, her voice wrapping the room in both beauty and dread. Nigerians knew too well the “fire” she described: ethno-religious violence, political crises, the constant rumble of unrest that made each day uncertain. Where Europeans had applauded the song’s poetic fatalism, Lagos heard prophecy.

By the time she slipped into Bibanke, the hall was hushed. “Bibanke” means I’m crying in Yoruba, and though she sang part of it in English, it was the Yoruba lines that pierced deepest. Women in the audience wept silently. Men shifted in their seats, eyes glassy. This was heartbreak that was not just romantic but communal—the grief of a people carrying too much loss.

It became clear that night: Asa had not only returned to Lagos. She had returned Lagos to itself.

The city, so often loud, allowed itself to be quiet with her. It bent its energy inward, reflecting instead of exploding. Lagos, which rarely listens, listened.

Critics later described the concert as a watershed moment for Nigerian music. Not because Asa was the loudest voice—she wasn’t. Not because she was the most commercial—she wasn’t. But because she reminded the city that its stories could be sung in whispers and still be heard. She opened the door for a new kind of artistry in Nigeria: introspective, global yet local, soulful without compromise. Artists like Bez, Brymo, and Nneka would walk through that door in the years that followed, each owing something to the quiet revolution Asa staged that night.

And in that hall, as the final chords lingered in the air, Lagos claimed her. Not as a visiting star from Paris, not as a borrowed name, but as one of its own.

The audience did not just clap. They stood, they roared, they cried. They gave her back the city she had risked everything to return to.

That was the night Asa sang Lagos into eternity.

The Album That Spoke in Two Languages

When Asa released her eponymous debut album in 2007, the world was finally given a permanent record of what Paris cafés and Lagos dreams had been whispering about for years. Simply titled Asa, it was more than a debut. It was a statement, a manifesto, a sonic passport that bore two stamps: one French, one Nigerian.

Produced by the Nigerian musician Cobhams Asuquo, the album was carefully balanced between the lush arrangements of Parisian studios and the raw, storytelling grit of Lagos life. For Asa, it was less about introducing herself to the world than about introducing Lagos to the world—on her own terms.

“Jailer”: A Song of Chains, Sung on Two Continents

The album opened with Jailer, her first major hit and still one of her most defining songs.

In Paris, the song was embraced as a universal protest against systemic injustice. Critics praised it as a subtle, soulful critique of authoritarian structures.

In Lagos, the same song cut deeper. Here, “Jailer” wasn’t an abstract metaphor. It was literal: young people who had been stopped by police, activists who had vanished behind prison walls, ordinary citizens paying bribes to buy freedom that should have been theirs.

The dual reception proved Asa’s genius. She had written a song broad enough to be universal, yet sharp enough to pierce Nigeria’s reality.

“Fire on the Mountain”: Prophecy in Melody

This track, deceptively calm in delivery, carried urgency like a ticking clock. When Asa sang, “There is fire on the mountain, and nobody seems to be on the run,” it felt like she was reading Nigeria’s headlines before they happened.

To Parisian audiences, it was a poetic metaphor.

To Lagosians, it was reportage. Ethno-religious clashes, political killings, and economic despair meant that fire on the mountain was not a parable but a permanent condition.

The song would become one of Asa’s most prophetic works, replayed whenever Nigeria stumbled into yet another crisis.

“Bibanke”: The Grief That Spoke in Yoruba

The Yoruba phrase Bibanke means “I’m crying.” And when Asa delivered it, she didn’t just describe heartbreak—she embodied it.

Sung partly in Yoruba and English, it showcased her ability to hold two worlds in one breath.

In Lagos, the Yoruba parts hit like lightning. The language of the streets, the language of mourning, gave the song emotional electricity.

It was the moment Asa reminded Nigerians that their languages could carry global weight without translation.

“Eye Adaba”: The Dove That Carried Hope

Translated as The Dove, Eye Adaba was an ode to peace, soft yet unbreakable. It became a quiet anthem, played at Nigerian weddings, political gatherings, and even in homes during moments of family reconciliation.

The track’s imagery of the dove symbolized hope in a country often gasping for it.

It also showed Asa’s spiritual dimension—an artist willing to sing about peace in a world obsessed with power.

“360 Degrees” and “No One Knows”: The Circle of Uncertainty

These tracks explored the cyclical nature of life and the mysteries of fate. Asa wasn’t only chronicling her Lagos upbringing or Paris journeys. She was asking existential questions that resonated universally. The world was unstable, and Asa voiced its instability.

I)The Global Reception

The album won the French Constantin Award in 2008, marking Asa as the first Nigerian to receive it. In Europe, critics placed her in the lineage of Tracy Chapman and Nina Simone, while in Nigeria, she was seen as opening a new frontier for musicians who didn’t fit into the mainstream Afrobeat or Afropop mold.

But more importantly, Asa became a kind of mirror. For Nigerians, it reflected their wounds and their resilience. For foreigners, it revealed a Nigeria they rarely saw—nuanced, poetic, thoughtful, intimate.

II)The Lagos Stamp

Even though the album was recorded in France, its spiritual home was Lagos. Every Yoruba lyric, every memory-laden chord, every protest woven into the songs carried Lagos with it. Paris may have been the production site, but Lagos was the source code.

And this was the paradox Asa embodied: she had left Lagos to be discovered, but the album that made her global was, at its heart, an ode to the city she could never abandon.

How Asa Changed the Sound of Lagos Forever

From year 2007, Lagos was already a cauldron of sound. Afrobeats was tightening its grip on dance floors, Nollywood was exporting Nigerian slang through film, and hip-hop had found a Lagos accent through artists like Mode 9 and Ruggedman. In that noisy, crowded landscape, Asa’s music was an interruption—an insistence on stillness.

Her debut album had carved out something Lagos didn’t know it needed: soul with Yoruba bones.

I)The Quiet Revolution

Lagos audiences were used to volume—music that competed with traffic, with generators, with the roar of a restless city. Asa, however, walked into that storm carrying silence like a weapon. Her acoustic guitar became a rebellion against the excesses of sound.

That was revolutionary. Because she proved you didn’t need to be loud to be heard in Lagos.

II) The Rise of the Alté Spirit

Though the term Alté (alternative) wouldn’t gain full recognition until nearly a decade later, Asa was laying its foundations.

Artists like Bez, Brymo, and Nneka found courage in her success.

They, too, began blending soul, R&B, and indigenous sounds, unconcerned about whether they fit into radio’s mold.

In many ways, Asa’s refusal of Paris was also her refusal of the commercial straitjacket of Nigerian music. By anchoring in Lagos while staying different, she opened a door for the next generation of misfits.

III) Women Could Lead Differently

Before Asa, Nigerian women in music were often boxed into narrow archetypes: the diva, the siren, the pop star. Asa gave a new model—the thoughtful troubadour. She wore dreadlocks, glasses, jeans. She was not adorned as spectacle, but she radiated authority through her authenticity.

That image inspired a generation of young Nigerian women who began to imagine careers outside the stereotypes. Singers like Tems and Arlo Parks (Nigerian-British) would later draw from that permission Asa granted.

IV) Lagos as a Listening City

One of Asa’s most subtle influences was cultural: she taught Lagos to listen. At her shows, people didn’t just dance—they sat, they cried, they reflected. Her concerts were communal therapy sessions disguised as music.

This created a new kind of performance culture in Lagos, where intimacy mattered as much as spectacle. Today, artists like Johnny Drille and Simi thrive in that space Asa first legitimized.

V) The Lagos Soundscape Rewritten

Before Asa, Lagos music largely oscillated between Afrobeat’s political grooves, Fuji’s street beats, and the rising wave of pop. After Asa, Lagos began to embrace soul and singer-songwriter traditions with Yoruba inflections. Her refusal of Paris planted a seed in her hometown: the idea that Lagos could be both global and deeply introspective.

This was not just about music—it was about identity. Asa redefined what it meant to be a Lagos artist: not only someone who entertained, but someone who documented the soul of the city in song.

Beautiful Imperfection: When Asa Painted with New Colors

By 2010, Asa had already proven she could carry Lagos on her shoulders with an acoustic guitar. But when she returned with her second album, Beautiful Imperfection, she surprised even her most loyal listeners.

The title itself was telling. It suggested an artist who had embraced her contradictions—Paris polish and Lagos grit, soul melancholy and pop optimism, Yoruba grounding and global fluency. Asa wasn’t running from those opposites anymore. She was weaving them together.

I) A Shift in Tone

Where Asa (2007) had been introspective, smoky, and heavy with social critique, Beautiful Imperfection opened its windows to let in more light. The arrangements were fuller, the rhythms more playful, the melodies sunnier.

Songs like Be My Man introduced a swing and sass that Lagosians had rarely seen from her. This wasn’t the Asa of “Bibanke” tears but of flirtation, boldness, and confidence. She was no longer the quiet revolutionary with a guitar—she was a woman owning her joy.

II) The Lagos Audience Responds

At first, some Lagos critics hesitated. They asked: was Asa softening? Was she turning toward Parisian pop sensibilities and leaving behind the Lagos soul that had birthed her?

But the audiences told a different story. Lagosians embraced Beautiful Imperfection with open arms.

Be My Man became a staple at weddings and parties.

Maybe echoed through radio stations, balancing groove with reflection.

Preacher Man carried the social commentary torch, proving Asa hadn’t abandoned her conscience.

What Paris heard as sophisticated world-pop, Lagos heard as a woman refusing to be boxed in.

III) The Feminine Evolution

With Beautiful Imperfection, Asa became more than a voice of protest—she became a voice of possibility. She wasn’t just the singer of pain; she was also the singer of love, of curiosity, of becoming.

For Nigerian women watching her ascent, this mattered deeply. Asa modeled a kind of womanhood that could be intellectual without losing joy, serious without being dour, spiritual without being confined.

IV) Performing Lagos Back to Itself

The tours that followed the album cemented Asa’s reputation as one of Nigeria’s most important live performers.

At Eko Hotel, her second major Lagos concert drew even bigger crowds than her debut.

She didn’t need backup dancers or pyrotechnics—her stagecraft was in her command of silence and the precision of her band.

When she performed Preacher Man, the audience swayed not with their bodies but with their convictions.

These performances turned Lagos into a different kind of audience—one that could appreciate subtlety, listen for nuance, and celebrate music that didn’t fit commercial formulas.

V) Paris Still Knocking

Meanwhile, in Paris, Asa was a darling of the music press. She appeared at jazz festivals, played sold-out theatre shows, and was praised as Nigeria’s most “global” artist. But the irony remained: while Paris provided stages, Lagos gave meaning.

Asa herself admitted in interviews that while she had grown in France, her stories could only have been born in Nigeria. The imperfections she sang of—the contradictions, the tensions, the beauty hidden in brokenness—were Lagos itself.

VI) The Dual Identity Solidified

By the time Beautiful Imperfection had run its course, Asa was no longer an artist torn between two cities. She was both.

To Lagos, she was a daughter who had refused exile.

To Paris, she was the foreigner who made their stages feel like home.

To herself, she was an imperfection—made beautiful because it could never be simplified.

Bed of Stone: Asa’s Descent into Depth

If Asa (2007) was the sound of arrival and Beautiful Imperfection (2010) was the sound of exploration, then Bed of Stone (2014) was the sound of confrontation. Asa’s third studio album stripped away the optimism of her previous work and replaced it with raw vulnerability.

The title alone—Bed of Stone—suggested hardness, weight, and permanence. It implied a rest that was anything but soft. For an artist whose career had been built on the delicate balance of Lagos and Paris, the album marked a turning point. Asa was no longer trying to bridge two worlds. She was trying to survive within herself.

I) The Sound of Maturity

From the opening track, it was clear that Asa had entered a new chapter. The production was darker, the arrangements sparer, the lyrics cutting deeper. This was Asa moving past the glow of early stardom and into the solitude of an artist wrestling with existence.

Where Beautiful Imperfection had danced, Bed of Stone sat still. It listened. It bled.

II) Songs of Weight and Wounds

“Dead Again” opened the album with a blunt statement: betrayal, pain, the feeling of dying while still breathing. It was a far cry from the playful confidence of Be My Man.

“Eyo” was one of the rare moments of light, inspired by Lagos’s own Eyo Festival. It was Asa’s reminder that joy could still be found in cultural memory, even amid heaviness.

“Satan Be Gone” carried echoes of gospel, a plea for deliverance from unseen battles.

“The One That Never Comes” explored yearning and the ache of waiting for a love that may never arrive.

Every track was a confession. Asa was no longer just chronicling Lagos or offering Parisian cafés a taste of Yoruba soul. She was turning inward, exposing herself in ways that felt almost uncomfortable.

III) How Lagos Received It

When Bed of Stone dropped in Nigeria, it didn’t dominate the airwaves. It was too heavy, too slow, too reflective for a city intoxicated by the rise of Afrobeats giants like Wizkid and Davido. Lagos wanted anthems for dance floors; Asa was offering dirges for broken hearts.

And yet, beneath the mainstream noise, the album sank roots.

It became a cult classic among young Nigerians searching for music that reflected their inner storms.

Universities, book clubs, and intimate concert circles adopted the album as a soundtrack for reflection.

For Lagos’s thinkers, writers, and lovers of solitude, Bed of Stone was a balm—a reminder that even in a city of chaos, one could pause and feel.

IV) Paris and the Global Echo

In Europe, the album was praised for its rawness. Critics compared Asa to Joni Mitchell and Tracy Chapman, noting her ability to balance personal confessions with universal resonance. But for Nigerians, the record carried something deeper: it was the sound of a daughter refusing to make her music “easier” for the marketplace.

Asa had chosen the harder road. And Lagos, even when it didn’t fully celebrate her, respected her.

V) The Courage of Stillness

The genius of Bed of Stone was not in commercial hits but in courage. Asa released it at a time when Nigerian music was becoming increasingly global, chasing charts and streaming numbers. She, instead, delivered a record of honesty, imperfection, and pain.

In doing so, she reasserted what her Lagos refusal of Paris had always meant: that she would not be dictated to by markets or expectations. Her art was her own, even if it meant fewer sales or slower applause.

VI) Eyo: Lagos Inside the Darkness

The standout Lagos moment on the album was Eyo. While the rest of the album leaned into grief and darkness, Eyo shimmered with nostalgia. Drawing inspiration from the traditional Yoruba masquerade festival, the song reminded listeners that even in hardship, Lagos culture carries joy and resilience.

It was a fitting metaphor: Asa could travel into darkness, but Lagos remained her light.

Lucid: The Return of Light After Shadows

By 2019, Asa had been absent from the studio for five years. In Lagos, that silence felt like an eternity. Nigerian music had changed dramatically in her absence:

- Wizkid was filling international arenas.

- Burna Boy had become the global face of Afro-fusion.

- Davido was translating Lagos pop into worldwide hits.

In this new landscape, there were questions: Did Lagos still have room for Asa’s quiet soul, her guitar-driven intimacy, her refusal to bow to trends?

I) A Softer Landing

When Lucid arrived, the answer was not in a fight but in a whisper. The album was stripped-down, melodic, and intimate—more personal diary than public spectacle. Asa didn’t try to compete with Afrobeats; she carved a separate lane altogether.

If Bed of Stone was about grief and confrontation, Lucid was about acceptance. It carried the calm of an artist who had survived storms and was now narrating the aftermath.

II) The Songs That Defined It

“Good Thing”: A bittersweet breakup song that framed leaving as liberation. It showed Asa’s ability to turn endings into beginnings.

“The Beginning”: A meditation on love, memory, and the cycles of human connection. Its simplicity was its strength.

“My Dear”: A song that revealed Asa at her most vulnerable, pleading without shame.

“Stay Tonight”: A rare spark of sensuality, hinting at a more playful Asa beneath the surface.

Each track was less about protest or politics and more about human fragility—love, loss, hope, longing.

III) Lagos Listens Differently

In 2019, Lagos was a city dancing to club hits and street anthems. Yet when Asa released Lucid, she reminded the city of another rhythm: the rhythm of stillness.

Couples used songs from Lucid as soundtracks to weddings and private anniversaries.

Radio stations carved out late-night slots for Asa’s tracks, spaces where her music could breathe.

Book clubs, poetry gatherings, and Lagos’s growing art cafés embraced the album as their anthem.

It was clear: Asa was not competing with Afrobeats. She was offering Lagos an alternative emotional register.

IV) Paris, Still in the Frame

In Europe, Lucid was received as a polished return to form. Critics noted its maturity, comparing Asa again to Tracy Chapman. But in Lagos, the reception was different. Here, Lucid felt like an artist speaking directly to her people after years of silence.

She wasn’t just returning with an album; she was returning with herself—older, scarred, but still rooted.

V) Asa’s Refusal, Reaffirmed

With Lucid, Asa once again affirmed her choice: she could have chased Parisian trends or Lagosian mainstream success. Instead, she stayed in her lane.

This refusal became her power. In a time when Nigerian artists were racing to conquer global charts, Asa seemed unconcerned. Her legacy was not in numbers but in depth.

VI) Lagos in the Lucid Mirror

The album reflected Lagos differently than her earlier work.

If Asa (2007) had shown Lagos its pain,

If Beautiful Imperfection (2010) had shown Lagos its joy,

If Bed of Stone (2014) had shown Lagos its grief,

Then Lucid (2019) showed Lagos its endurance.

It said: You are still here. After heartbreak, after struggle, after silence—you are still here.

When Asa Opened the Door to a New Generation

By 2022, Asa was already an institution—revered, respected, sometimes mythologized. She had spent nearly two decades proving that Lagos could hold its own against Paris, that Nigerian music could whisper as powerfully as it shouted.

But with her fifth studio album, V, Asa did something no one expected: she let the new Lagos in.

I) The Shift Nobody Predicted

Until V, Asa had largely kept her sound insulated from Nigeria’s booming Afrobeats wave. She had maintained her own lane—guitar-driven, introspective, soulful. But on this album, she invited collaborations with younger Nigerian artists like Wizkid’s contemporary The Cavemen, and Afro-fusion voices like Amaarae.

The result was a record that sounded playful, even flirtatious. It was Asa in dialogue with a generation that had grown up listening to her but had since taken Nigerian music global.

II) Songs That Redefined Her Space

“Mayana”: The album’s lead single, with its lilting groove, surprised fans who expected melancholy. It was lighter, freer, more playful—a lover’s promise to “sail away.” Lagos received it not as Asa selling out, but Asa loosening up.

“Ocean”: A sweeping ballad where her old introspection met new textures.

“Good Times” (feat. The Cavemen): A highlife-infused track that paid homage to Nigeria’s rich musical past while sounding utterly fresh. It was Asa laughing, dancing, and drinking palm wine with the next generation.

“Love Me or Give Me Red Wine”: Bold, sensual, teasing—the kind of vulnerability Asa had once only hinted at.

III) Lagos Reacts to a New Asa

For Lagos audiences, V was both a shock and a celebration. Some longtime fans initially resisted the lighter sound, calling it “too pop” or “too easy.” But younger listeners embraced it immediately.

Suddenly, Asa wasn’t just the soundtrack of book clubs and quiet nights—she was on playlists alongside Wizkid, Tems, and Burna Boy. Lagos club DJs began sneaking Mayana into sets. Weddings danced to Good Times.

The city had always claimed Asa, but now a new generation was discovering her on their own terms.

IV) Paris and the World Take Note

International critics saw V as Asa’s reinvention. For years, she had been compared to Nina Simone and Tracy Chapman—serious, reflective, weighty. With V, they realized she could also be compared to Sade or Angelique Kidjo—artists who carried depth but weren’t afraid of joy.

This mattered because it shattered the myth of Asa as “forever melancholic.” She proved she could evolve, and in doing so, she echoed Lagos itself: a city that never stops reinventing its sound.

V) A Dialogue Between Generations

Perhaps the most important impact of V was symbolic. By working with younger artists, Asa bridged Lagos’s musical past and present. She showed that legacy doesn’t have to be rigid—that it can laugh, dance, and share space with the future.

In that sense, V was Asa’s most Lagos album yet. Not because it was traditional, but because it embodied Lagos’s true spirit: adaptation without loss.

VI) Refusing Paris, Embracing Lagos Again

With V, Asa reaffirmed what she had always known: Paris could refine her sound, but Lagos was her compass. No matter how far she traveled, it was Lagos that told her when to weep (Bibanke), when to reflect (Eyo), when to endure (Lucid), and now—when to dance (V).

Legacy of a City in a Voice

By the time the lights dimmed on Asa’s fifth act, Lagos was no longer just a city in her story. It had become her co-writer. Every note she ever bent, every silence she ever allowed to linger, carried traces of the streets, markets, and voices of Lagos.

Paris might have given Asa polish. Lagos gave her pulse.

Her decision to return, to center Lagos in her life and art, was more than geography. It was philosophy. It was a quiet rebellion against the narrative that Nigerian artists had to seek validation elsewhere. Asa showed that you could leave Lagos to find yourself, but you had to return to Lagos to remain true.

Why Paris Couldn’t Hold Her

Paris had once offered Asa the freedom Lagos denied her: space to experiment, to record, to be taken seriously as an artist. But Paris, with all its refinement, lacked Lagos’s fire.

Paris applauded her artistry. Lagos felt it in its bones.

Paris offered stages. Lagos offered belonging.

Paris understood her lyrics. Lagos understood her silences.

It was this difference that defined her refusal. Asa wasn’t turning her back on Paris—she was simply acknowledging that Paris could never contain her whole story. Only Lagos could.

A Legacy Written in Two Languages

Asa’s life has been a dance between two languages, two cities, two worlds. But her music made them speak to each other.

She took Yoruba proverbs and slipped them into chords that Paris critics called “folk elegance.”

She lifted Parisian melancholy and wove it into Lagos lullabies.

She reminded Nigerians that global recognition didn’t mean abandoning home.

Her legacy is therefore not just about music but about translation—between continents, between generations, between silence and sound.

The Eternity She Sang Into

When Asa sings in Lagos, the city doesn’t just listen—it remembers. It remembers its colonial past, its hopeful independence, its chaos and creativity. In Asa’s voice, Lagos hears itself reflected with dignity.

And that is why the night Asa refused Paris wasn’t just about a single decision. It was about an eternity she built:

- For the young girl in Lagos holding a guitar, dreaming without permission.

- For the old man on the Island who remembers Fela and recognizes the same courage in Asa’s restraint.

- For the diaspora Nigerian in Paris who hears Lagos every time Asa breathes between notes.

This eternity isn’t carved in monuments or in buildings—it is sung, night after night, whenever Asa steps on stage and lets Lagos speak through her.

A Lasting Thought: Lagos as Asa’s Eternal Stage

In the end, Asa’s career is less a series of albums and more a series of homecomings. Each record marked a journey outward, but every journey bent back to Lagos, like tides returning to shore.

Asa (2007) was Lagos declaring its pain.

Beautiful Imperfection (2010) was Lagos daring to dream.

Bed of Stone (2014) was Lagos enduring heartbreak.

Lucid (2019) was Lagos surviving vulnerability.

V (2022) was Lagos dancing again.

This cycle is why Asa will remain timeless. She didn’t just give Lagos a soundtrack—she gave it eternity.

The night she refused Paris was not one night, but every night she chose to sing Lagos into the world. And as long as Lagos exists, Asa’s voice will echo, reminding the city—and us—that sometimes the greatest act of art is not leaving, but returning.