There was a time when television in Nigeria was not background noise, not the idle chatter of sitcoms flickering while someone scrolled a phone, not the endless scroll of Netflix thumbnails waiting for a restless hand to decide. It was something closer to ceremony. Something closer to silence before prayer.

- The Forgotten Architects: Who Birthed the Sacred Screen

- The Children on Screen: A Nation’s Mirror

- Episodes That Lingered: Lessons Under the Moonlight

- Storytelling as Ceremony: Why It Felt Sacred

- Moonlight and Memory: Why It Still Haunts the Mind

- Why Sacredness Died: The Age of Noise

- The Streaming Deluge: Too Much, Too Fast

- Echoes in Nollywood and Beyond

- The Sacred Screen and National Unity

- Conclusion: The Moon Has Set, But Its Light Remains

The night would descend slowly, shadows thickening over Lagos, Ibadan, Kano, Port Harcourt. Inside the homes, the low hum of a generator or the brittle glow of a kerosene lamp filled the air. And then, as if on cue, children would drift toward the television — that box of light, that humming oracle, that machine that turned stories into something almost holy.

When the Tales by Moonlight theme music began, there was a stillness that fell on Nigerian living rooms. Not silence in the sense of emptiness, but silence in the sense of reverence. The way villagers once gathered under a great tree to hear elders spin wisdom, children now gathered under a different light — the phosphorescent glow of the NTA screen.

It felt bigger than entertainment. It felt bigger than distraction. It felt like a communal heartbeat, pulsing through millions of homes at the same time. To watch Tales by Moonlight was to partake in a ritual that every child in the country seemed bound by. You were not just watching television; you were entering a sanctuary.

This was the last time television in Nigeria felt sacred. And the question that lingers, decades later, is why.

The Forgotten Architects: Who Birthed the Sacred Screen

Every sacred object has its custodians, and Tales by Moonlight was no different. Behind the children seated cross-legged on woven mats, behind the smiling storyteller gesturing under an artificial tree, stood producers, writers, and directors who understood the delicacy of their mission.

The Nigerian Television Authority in the early 1980s was not the disheveled bureaucracy we often remember. It was then a hub of creative ambition. The producers believed television could shape identity. They recruited folklorists, teachers, and performers to translate oral tales into broadcast form.

Names like Nkem Oselloka-Orakwue — anchor and storyteller — became cultural custodian. She was not just reading lines. She and her crew carried on their shoulders the ancestral responsibility of being griots for a new generation. Unlike Hollywood actors, their task was not glamour but guardianship. Each episode was crafted to balance fidelity to folklore with accessibility to a child watching from a Lagos flat or a Kano courtyard.

In production archives, you find notes about costuming — should the storyteller wear Ankara wrappers, or adopt a neutral modern outfit? Should the children be barefoot, or dressed in clean uniforms? Even these small details carried weight. Too much “modern” and the magic was lost. Too much “traditional” and the urban child might switch off.

It was, in effect, a national experiment in cultural engineering. And for nearly two decades, it worked.

The Children on Screen: A Nation’s Mirror

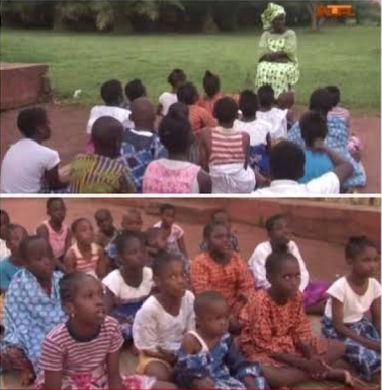

One of the most striking images of Tales by Moonlight was not the storyteller but the children who sat in semi-circles, eyes wide, bodies leaning forward, clapping, laughing, gasping. They were not just extras — they were mirrors.

For a Nigerian child watching from home, these were not strangers. They were surrogates. They looked like the cousins in the village, the classmates at school, the neighbors in the compound. In a way, they validated every viewer. They signaled that you belonged to the story.

Sociologists argue that representation is never neutral. To see children who looked like you on national television, absorbed in folktales you knew, was an act of affirmation. In that simple staging, Tales by Moonlight gave millions of Nigerian children permission to feel that their culture mattered, that their identity had a screen-worthy dignity.

Episodes That Lingered: Lessons Under the Moonlight

Certain stories etched themselves into memory not because of flashy production, but because of their moral gravity.

The Tortoise and the Feast in the Sky: The tale of Ijapa, who tricked birds into lending him feathers so he could attend a celestial feast. Greedy, he renamed himself “All of You” to claim the food. When the trick unraveled, he was cast down from the sky, his shell shattering — the mythological origin of the tortoise’s cracked shell. Children watching did not just laugh. They internalized the peril of greed and dishonesty.

The Lazy Hunter: A man who avoided labor relied on trickery, only to be caught by his own schemes. The story rang especially loud in a country battling economic hardship, where elders constantly reminded children that diligence was survival.

The Girl Who Disobeyed Her Parents: Stories often emphasized obedience, respect, and caution — core values of Nigerian societies. These narratives reinforced cultural expectations, reminding children that defiance had consequences.

Each episode functioned as a parable. But unlike Western cartoons where morals were often tacked on awkwardly at the end, Tales by Moonlight embedded its lessons seamlessly. Nigerian children absorbed ethics the way they absorbed air.

Storytelling as Ceremony: Why It Felt Sacred

What made Tales by Moonlight sacred was not simply its content but its form. Every element mirrored the cadence of ritual:

The gathering — children sat around the storyteller in a semi-circle, echoing the village square.

The atmosphere — soft lighting, gentle music, and a narrator’s calm voice created intimacy.

The moral arc — every story ended with a lesson, a guiding principle.

To a child, it felt as if the show was not just speaking to you but consecrating you — inducting you into a heritage.

Oral traditions across Nigeria were never merely entertainment. They were tools of cultural transmission. They embedded proverbs, warnings, and wisdom inside the skins of fantastical creatures. In Yoruba tradition, the tortoise (Ijapa) was cunning but greedy; in Igbo folklore, the trickster was punished by his own schemes. These were not just bedtime stories. They were ethical maps.

Tales by Moonlight carried this weight onto the national screen. And in doing so, it gave television — a modern, imported technology — the aura of an ancestral ceremony.

Moonlight and Memory: Why It Still Haunts the Mind

Psychologists studying nostalgia argue that what makes certain cultural artifacts endure is not just content but context. A song, a story, or a show endures because it is tied to a ritual, a place, a rhythm of life that no longer exists.

For Tales by Moonlight, the ritual was sacred time. Sunday evenings, after chores and before bedtime, when the compound was settling, when parents were finishing their dinners and children still had energy to absorb. The show came not randomly but rhythmically. It became woven into the body clock of a generation.

That is why today, a simple audio clip of its opening theme can trigger goosebumps. It is not the melody itself but the memory of what surrounded it — the warm presence of siblings, the smell of dinner cooking, the stillness before school on Monday. To recall Tales by Moonlight is to recall childhood itself, to recall a country where time felt slower, more unified, less fragmented.

Why Sacredness Died: The Age of Noise

Television’s sacredness is not natural; it is constructed. It requires scarcity, ritual, limitation. Once those vanished, the aura cracked.

In the 1990s, the arrival of satellite channels changed everything. DSTV, Cartoon Network, MTV, and foreign soap operas expanded the menu. Suddenly, Nigerian children had alternatives that sparkled with color, speed, and foreign glamour. Tales by Moonlight seemed quaint beside American cartoons where superheroes flew and explosions abounded.

The NTA itself declined. Chronic underfunding left sets looking outdated. Technical glitches broke immersion. Producers struggled to compete with the polish of imported content. Sacredness gave way to mediocrity.

By the 2000s, sacred television was dead. In its place was abundance — but abundance without ceremony.

The Streaming Deluge: Too Much, Too Fast

The streaming revolution accelerated what satellite began. Netflix, YouTube, Amazon Prime, TikTok — platforms designed for endless choice and distraction — dismantled the conditions under which sacred television could thrive:

- Sacredness thrives on waiting. Streaming thrives on immediacy.

- Sacredness thrives on collective alignment. Streaming thrives on personalization.

- Sacredness thrives on scarcity. Streaming thrives on abundance.

The paradox is clear: the more content we gained, the less meaning each piece carried. Nigerian children today may consume hundreds of shows, but none of them will etch themselves into memory with the weight of Tales by Moonlight. None will bind them to millions of peers across the country at the same hour.

The cathedral has become a shopping mall.

Echoes in Nollywood and Beyond

Still, the DNA of Tales by Moonlight has not vanished. Nollywood filmmakers, many of whom grew up on the program, continue to echo its storytelling structures. The archetypal trickster, the punished greedy man, the rewarded humble child — these figures populate countless Nollywood films.

In educational programming, attempts like Story Story on radio and newer children’s shows online seek to revive folklore. Yet none have achieved the same national grip. The ritualized broadcast hour cannot be recreated in the era of on-demand streaming.

Even the diaspora carries echoes. Nigerian parents abroad often retell Tales by Moonlight episodes to children who have never seen the show. It has become folklore about folklore — stories about a show that once told stories.

The Sacred Screen and National Unity

Beyond nostalgia, the show’s greatest achievement may have been national cohesion. Nigeria is a country forever grappling with division — north and south, Christian and Muslim, Yoruba and Igbo and Hausa. Tales by Moonlight was one of the few programs that transcended these fractures.

It did not privilege one language or ethnicity. Instead, it offered a common space where all could see themselves. In a subtle way, it performed nation-building work. It said: we are different, but these are our shared myths.

That role is almost unimaginable today, when media consumption is fragmented by language, by class, by algorithm. The sacred screen that once united is now a thousand fractured feeds.

Conclusion: The Moon Has Set, But Its Light Remains

Sacredness is not in the content alone. It is in the ritual of gathering, the scarcity of access, the reverence of time. Tales by Moonlight was sacred because it demanded pause, because it gave Nigerian children a common mythology, because it was both modern and ancestral at once.

Today, television no longer commands that reverence. It has dissolved into noise, into abundance, into lonely consumption. But memory resists. The sacred glow of Tales by Moonlight remains in the hearts of those who once gathered, once listened, once believed.

The moon has set. But even in darkness, its afterlight still lingers — in memory, in nostalgia, in the unbroken truth that stories, when told with reverence, are never truly lost.