It began with a sound. Not music this time, but the sharp, crushing screech of metal folding against metal on a dark Lagos road. In that moment, a voice that had once commanded the city’s attention was reduced to silence.

- The Rise Before The Deaths

- Yoruba Rap and the Rebellion of Sound

- The Last Days: A Timeline of Fire and Silence

- First Death: The Night of the Crash

- The Quiet Erosion of a Legacy

- The Heirs of a Fallen King

- Yoruba Rap After Dagrin: Survival or Transformation?

- The Ghost That Refused to Fade

- Leaving With This: The Two Deaths

Before the crash, that voice had belonged to a young man who rapped in Yoruba with the fury of a prophet and the swagger of the streets. His words cut through Lagos noise like a blade, narrating the hunger, ambition, and defiance of a generation born in struggle. In the slums of Mushin, where broken ceilings leaked rainwater and boys rehearsed survival daily, his rhymes were gospel. To the music industry, he was disruption. To his fans, he was hope.

The streets crowned him long before the record labels did. His name began to travel — whispered in taxis, scribbled on CD jackets, passed along from one neighborhood to the next. For young Nigerians who felt invisible, he was a mirror. For the elite music circles, he was a question mark.

Then, in a span too short to contain his promise, everything changed.

His name is still spoken today with a mixture of pride and ache. To talk about him is to talk about Lagos, about the struggle that shapes artistry, about the fragile line between survival and collapse. His life was lightning in a bottle; his story, a parable about dreams, destiny, and the price of being both.

This is not just a biography. It is a journey into the making of a legend whose fire burned too briefly, and whose absence still leaves a shadow.

For him, there are two deaths — one sudden, the other slower, quieter, and perhaps even more devastating.

This is the story of Dagrin.

The Rise Before The Deaths

From Mushin Streets to Musical Crown

Every great legend begins in obscurity, and Dagrin’s story was no different. Born on October 25, 1984, in Mushin, Lagos, his childhood was marked by the hard edges of urban survival. Mushin was a neighborhood of contradictions — alive with culture and resilience, but equally infamous for crime, poverty, and overcrowding. It was here, in the chaos of Lagos’s inner city, that Oladapo discovered the twin forces that would define his life: struggle and rhythm.

Music in Mushin wasn’t just entertainment. It was escape. From the Fuji beats echoing through late-night parties to the imported hip-hop cassettes passed hand-to-hand among restless youths, sound became a language of resistance. Dagrin absorbed it all. He watched the rise of pioneers like Lord of Ajasa, who had dared to rap in Yoruba when English still dominated Nigeria’s hip-hop scene. But while others experimented, Dagrin sharpened Yoruba rap into something rawer, harder, and more immediate.

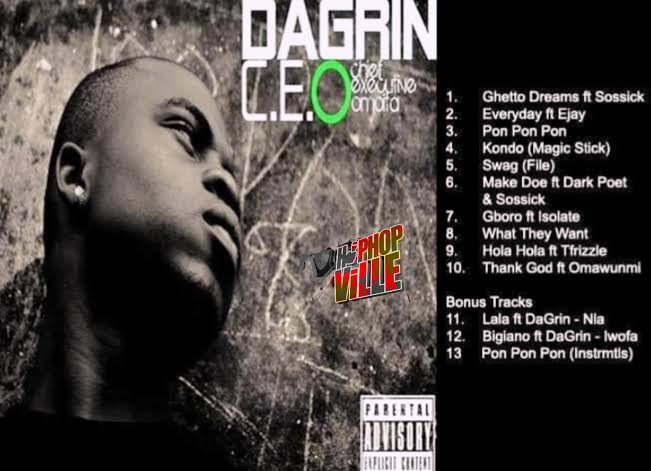

In 2009, his second album, C.E.O. (Chief Executive Omoita), detonated like a grenade. It wasn’t just music; it was a manifesto. With tracks like Pon Pon Pon and Kondo, Dagrin carried Mushin’s frustrations into the mainstream. His name became synonymous with the streets — not the gilded boulevards of Ikoyi or Victoria Island, but the grinding alleys where survival was the only daily ambition.

For once, ghetto boys had a hero who spoke exactly like them, in their language, with their cadence, without apology.

Yoruba Rap and the Rebellion of Sound

Before Dagrin, Yoruba rap was treated as a novelty, a side act to “serious” English bars. Nigerian hip-hop was chasing American models, mirroring Jay-Z, 50 Cent, and Nas. Dagrin refused that template. He flipped the hierarchy. Yoruba wasn’t a gimmick — it was the engine. He spat his rhymes with the full tonal richness of the language, weaved idioms, proverbs, and street slang into a firestorm of authenticity.

Where others sought global recognition, Dagrin fought for local resonance. In his lyrics, he captured the ache of a generation: boys without fathers, homes without roofs, futures without certainty. He embodied Lagos itself — restless, abrasive, and poetic. His charisma wasn’t polished; it was jagged. But it was precisely that jaggedness that resonated with a youth population tired of polished lies.

By late 2009, he was everywhere. Radio DJs couldn’t ignore him. Alaba marketers couldn’t keep his CDs on their shelves. Club crowds shouted his lyrics back at him, word for word, with the kind of fervor usually reserved for prayers. Dagrin had achieved what every artist dreams of: he made his audience see themselves in his story.

And then, just as the music reached its crescendo, life cut it short.

The Last Days: A Timeline of Fire and Silence

Studio Nights and Premonitions

The final weeks of Dagrin’s life carried the urgency of a man running against time. He was constantly in studios — from Surulere basements to Ikeja sound rooms — laying down features, verses, and hooks. Producers recall him arriving late at night, drained but unstoppable, his voice roughened by exhaustion, yet sharpened by hunger.

He recorded verses with YQ, worked on collaborations with emerging artists, and spoke often of taking Yoruba rap beyond Lagos. There were whispers of an international tour, of music videos that would rival the gloss of American hip-hop. He was twenty-five, burning with ambition, convinced that every second had to count.

But layered in his lyrics were premonitions. In If I Die, his voice carried an almost prophetic weight. The song wasn’t a surrender — it was defiance in the face of mortality. He rapped of legacy, of memory, of refusing to be erased. Fans later replayed those bars as though they contained hidden messages, a warning that he had glimpsed something no one else had.

First Death: The Night of the Crash

April 14, 2010. The city pulsed as it always did — restless, sleepless, dangerous. Dagrin was behind the wheel of his Nissan Maxima, navigating the darkened stretch of Alapere in Lagos Mainland. The details remain a blend of eyewitness fragments and official reports, but the outcome was undeniable. At around 3 a.m., his car collided with a stationary truck parked improperly on the roadside.

The impact was catastrophic. The Nissan crumpled like foil against steel. Lagos, a city all too familiar with the tragedies of its bad roads, was once again witness to preventable disaster. Dagrin was pulled from the wreck, critically injured, and rushed to Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH).

For days, he lingered between life and death. Friends, fans, and family gathered in anxious clusters outside the hospital. Rumors spiraled. Some said he was conscious and joking with nurses. Others swore he was in a coma. In the age before instant social media verification, uncertainty itself became a form of torture.

On April 22, 2010, the waiting ended. At 6 a.m., Dagrin was pronounced dead. He was 25.

Lagos in Mourning

News travels fast in Lagos, but grief moves faster. By mid-morning, the city was trembling with disbelief. Radio stations abandoned playlists to run tributes. Newspapers rushed out special covers. Fans gathered spontaneously at his family home in Meiran, some weeping, others rapping his lyrics through tears.

The hip-hop community was shattered. Dagrin had not only carried the torch for Yoruba rap; he had redefined what was possible. He was the one they thought would breach the invisible wall separating street credibility from mainstream dominance. Now, in one brutal moment, that promise was extinguished.

Across Nigeria, the mourning wasn’t confined to music lovers. Even those who had never listened to him felt the weight. Dagrin had represented something larger: the possibility of rising from Mushin dust to national stardom. His loss was collective, almost symbolic — a reminder of how fragile hope can be in a country where young lives burn out too fast.

For Lagos, it was the first death of Dagrin. The physical one. The sudden void where there had been music, laughter, and fire.

The Second Death

The Funeral and the Myth of Immortality

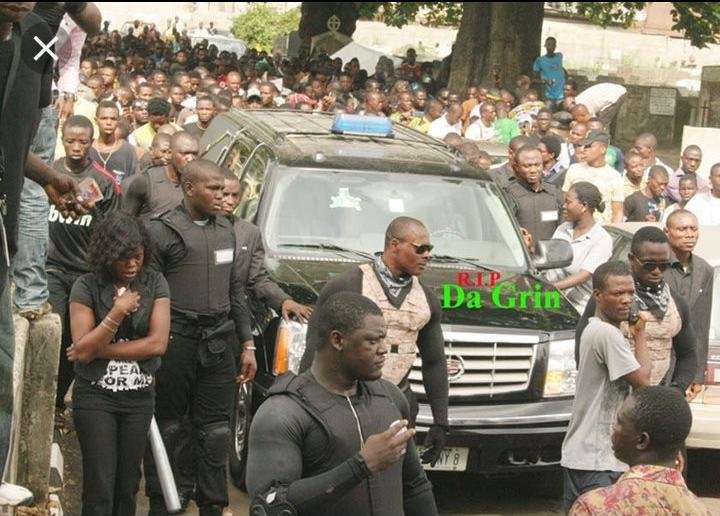

On April 30, 2010, Lagos came to a standstill. Crowds surged through the streets, drawn not by celebration but by loss. Dagrin’s body, wrapped in finality, was carried to Atan Cemetery. The hearse moved slowly, trailed by buses, motorcycles, and cars packed with mourners. Some came dressed in black, others in customized T-shirts emblazoned with his face, but all shared the same hollow disbelief.

For his family, it was a private sorrow made unbearably public. His mother’s grief, heavy and raw, became the face of Nigeria’s mourning. His father, silent and stoic, stood as though carrying an invisible burden that no parent should ever bear. Friends and fellow musicians tried to hold themselves together, but their eyes betrayed the truth: they had lost not just a colleague but a brother.

At the graveside, prayers were whispered, tears flowed, and music — his music — filled the air. Lyrics from Pon Pon Pon and Kondo became dirges. As the coffin was lowered, something paradoxical happened: while one life ended, a myth began. Dagrin was no longer just a rapper; he was becoming a legend.

But legends, too, can suffer erasure.

The Quiet Erosion of a Legacy

After the initial shock of his passing, Dagrin’s name was everywhere — radio tributes, street memorials, social media chatter, and crowded vigils. The ghetto had lost its voice, and the nation mourned. But the spotlight moved quickly, as it always does. New artists emerged. Afrobeats exploded internationally. The streets that had once chanted his lyrics now followed other beats.

This is where the second death begins. It was not sudden. It was quiet, almost imperceptible — the slow fading of his presence in the very culture he had helped shape. His songs stopped charting. Younger audiences grew up without knowing him live. Music executives, in their pursuit of commercial success, often sidelined the very raw authenticity Dagrin represented.

The tragedy was paradoxical: he had become immortal in story, yet mortal in memory. While tributes persisted, the daily pulse of Nigerian music — radio stations, club playlists, and mainstream media — moved on. Yoruba rap, the genre he had elevated, became a niche rather than a force. For the first generation that did not witness him in the studio or on stage, Dagrin risked becoming a name they only recognized secondhand.

The Industry’s Role in Forgetting

Many argue that the industry itself played a part in this erasure. Unlike Western markets, Nigeria had no formal archiving, little historical preservation for artists, and a culture that prizes the new over the foundational. The machinery that had celebrated Dagrin in death failed to cement his memory in life. Interviews and collaborations that could have sustained his legacy were left unfinished. The second death was structural: the failure of the music ecosystem to honor and preserve its own pioneers.

The Heirs of a Fallen King

Olamide – The Crown Bearer

In the shadows of Dagrin’s fall, Olamide Adedeji emerged. His debut album, Rapsodi (2011), bore Dagrin’s fingerprints: gritty Yoruba flows, street energy, raw defiance. Olamide often acknowledged Dagrin as a blueprint, carrying Yoruba rap into mainstream dominance. His eventual empire — YBNL — was, in many ways, the kingdom Dagrin never lived to build.

Reminisce – The Street Oracle

Reminisce found his stride after Dagrin’s death, perfecting the art of weaving Yoruba and Pidgin into rap. Songs like Local Rappers carried echoes of Dagrin’s unapologetic embrace of street identity. He became the elder statesman of Yoruba rap, reminding fans that Dagrin’s fire had not been extinguished, only redistributed.

CDQ and the New Wave

For CDQ and younger rappers, Dagrin was the pioneer who proved that Yoruba rap could sell records, fill arenas, and command respect. Each of them carried fragments of his legacy, keeping his cadence alive in new rhythms.

Through them, his second death — cultural erasure — was resisted. They turned his absence into a foundation, a place to stand and reach higher.

Yoruba Rap After Dagrin: Survival or Transformation?

The Nigerian music industry in the 2010s and 2020s shifted toward Afrobeats, global collaborations, and polished pop aesthetics. Rap, especially in local languages, often felt sidelined. Yet Yoruba rap never vanished. It mutated.

Artists like Olamide blended rap with pop hooks, creating hybrid tracks that could dominate clubs and radio. Burna Boy, though primarily Afrofusion, carried the ethos of truth-telling that Dagrin had championed. Even Wizkid’s early rap verses carried shades of the Mushin-born rebel.

But purists argue something was lost. Dagrin’s music wasn’t just about entertainment; it was reportage. It was the newspaper of the ghetto, delivered in rhyme. Without him, Yoruba rap sometimes became diluted — more style than substance. Yet even in dilution, his shadow lingered, reminding everyone of what authenticity once sounded like.

The Ghost That Refused to Fade

Dagrin’s Posthumous Influence

Yet death, even the second kind, is never total. Dagrin’s spirit has refused to stay buried. His lyrics, especially the haunting line “If I die, make you no cry for me…” became eerie prophecy. For fans, those words cemented his status as Nigeria’s Tupac: a voice that seemed to foresee its own silencing.

The Cult of the 27 Club, Nigerian Edition

Globally, music history has its pantheon of artists who died young — Tupac, Biggie, Amy Winehouse, Kurt Cobain. Dagrin’s passing at 25 placed him just shy of the infamous “27 Club.” Yet in Nigeria, his death occupies a similar cultural weight. He became the cautionary tale, the eternal youth, the one who never grew old enough to betray his message.

Fans often speculate what could have been: Would he have gone international like Wizkid or Burna Boy? Would he have redefined Yoruba rap in an industry now obsessed with global markets? The questions linger unanswered, feeding the ghost story that surrounds his name.

Leaving With This: The Two Deaths

The story of Dagrin is not only about music. It is about mortality and memory. His first death came on April 22, 2010, when his body gave way to wounds from the crash. The second came slowly, invisibly, as the industry moved on and the culture threatened to forget him.

But there is also a third possibility — immortality. As long as his music plays in the corners of Mushin, as long as young rappers still find courage in his Yoruba bars, as long as his April death brings remembrance, Dagrin lives. Legends are never fully buried. They resurface in echoes, in whispers, in beats that refuse to fade.

In the end, the two deaths of Dagrin remind us of a truth Lagos itself knows well: the body may perish, the memory may dim, but the spirit — if fierce enough — will haunt forever.