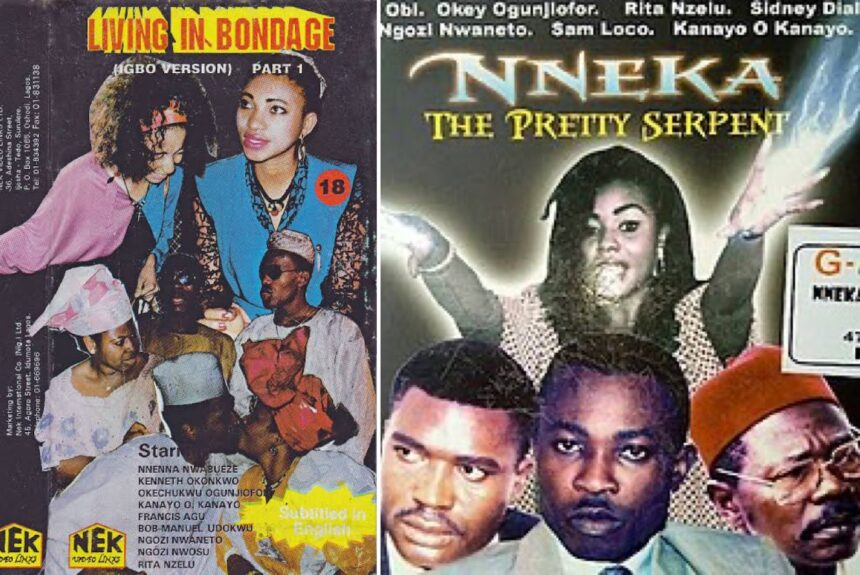

There was a time when Nollywood horror could make you sleep with the lights on. Back in the ’90s and early 2000s, films like Eran Ìyá Òsogbo, Kòtò Ayé, Nneka the Pretty Serpent (1994), and Living in Bondage (1992) shook entire households. People whispered about the stories for weeks, and some even refused to watch alone.

Fast-forward to today and things feel… different. Despite a few attempts like (Ile Owo, The Origin: Madam Koi-Koi, Hex, Living in Bondage: Breaking Free), Nigerian horror rarely leaves audiences trembling. Instead, many leave the cinema amused, or at best, mildly entertained. The question is: why don’t our horror films scare us anymore?

Back Then: Fear Rooted in Reality

The horror movies of the ’90s worked because they pulled directly from cultural fears. Ritual killings, witchcraft, village curses, snake brides etc, weren’t far-fetched ideas. They were rooted in folklore and urban legends that Nigerians grew up hearing. Living in Bondage, for instance, turned everyday anxieties about money rituals into a story so believable it changed how people saw sudden wealth.

When Nneka the Pretty Serpent slithered onto screens in 1994, people were genuinely unsettled by the thought of a beautiful woman being possessed by marine spirits. The Yoruba classics like Eran Ìyá Òsogbo and Kòtò Ayé used chants, eerie drums, and village superstitions to make even ordinary trees feel haunted.

Horror then was effective because it was familiar. It reflected the things people already feared in real life.

Now: When Horror Feels Too Predictable

Today’s horror movies don’t always land the same punch. Why?

• Overused theme: The “possessed woman,” the “evil mother-in-law,” the “ritual gone wrong”… we’ve seen them so many times they no longer shock us.

• Polished but shallow: Films like The Origin: Madam Kóí-Kóó(Netflix) had sleek cinematography but lacked the raw dread of the urban legend it was based on. It looked good, but it didn’t haunt.

• Weak scares: Ilé Owó (2022) promised thrills but left many viewers feeling the tension never built strongly enough.

• Predictable pacing: Instead of slow-burn suspense, many films jump too quickly into jump-scare territory, leaving little time for dread to sink in.

Viewers end up admiring the effort but don’t actually feel scared.

Real Life Has Become Scarier

Another reason horror struggles is because Nigeria itself is filled with real-life horror. From economic hardship to insecurity, many viewers already live in a state of anxiety. What film can compete with the daily news? The “ritual killer in the village” plot that once terrified is now overshadowed by constant headlines about kidnappings, fraud, and corruption.

In other words, Nollywood horror sometimes feels tame compared to real life.

Technical Gaps: Sound, Effects, and Censorship

Horror relies heavily on sound design, lighting, and special effects. A creaking floorboard, a sudden blackout, a chilling whisper… these small details make or break a horror film. Unfortunately, many Nigerian productions still struggle with these technical areas. Poor sound mixing, overused stock effects, or unrealistic Computer-Generated Imagery (CGI) often break immersion.

Censorship and exhibitor bias also play a role. The Cinema Exhibitors Association of Nigeria (CEAN) has admitted it rejects many horror films because they “don’t sell.” So filmmakers either tone things down to get their films shown, or avoid the genre altogether. The few who push forward sometimes self-censor, robbing their work of edge.

How Nigerian Horror Can Get Scary Again

The good news is horror isn’t dead. Here’s how Nollywood can hopefully revive it:

1. Return to Folklore: Our culture is full of chilling myths. From Madam Koi-Koi, to bush babies, river goddesses, and masquerades that never go home. Telling these stories with authenticity, not just gloss, can bring back the dread.

2. Invest in Atmosphere, Not Just Jump Scares: Sound, lighting, silence, and tension are everything. A dark corridor with distant chanting can scare more than bad CGI.

3. Update the Fears: Horror should reflect what we fear now. Imagine a horror story about social media curses, AI gone wrong, or spiritual scams. Relevance makes fear real.

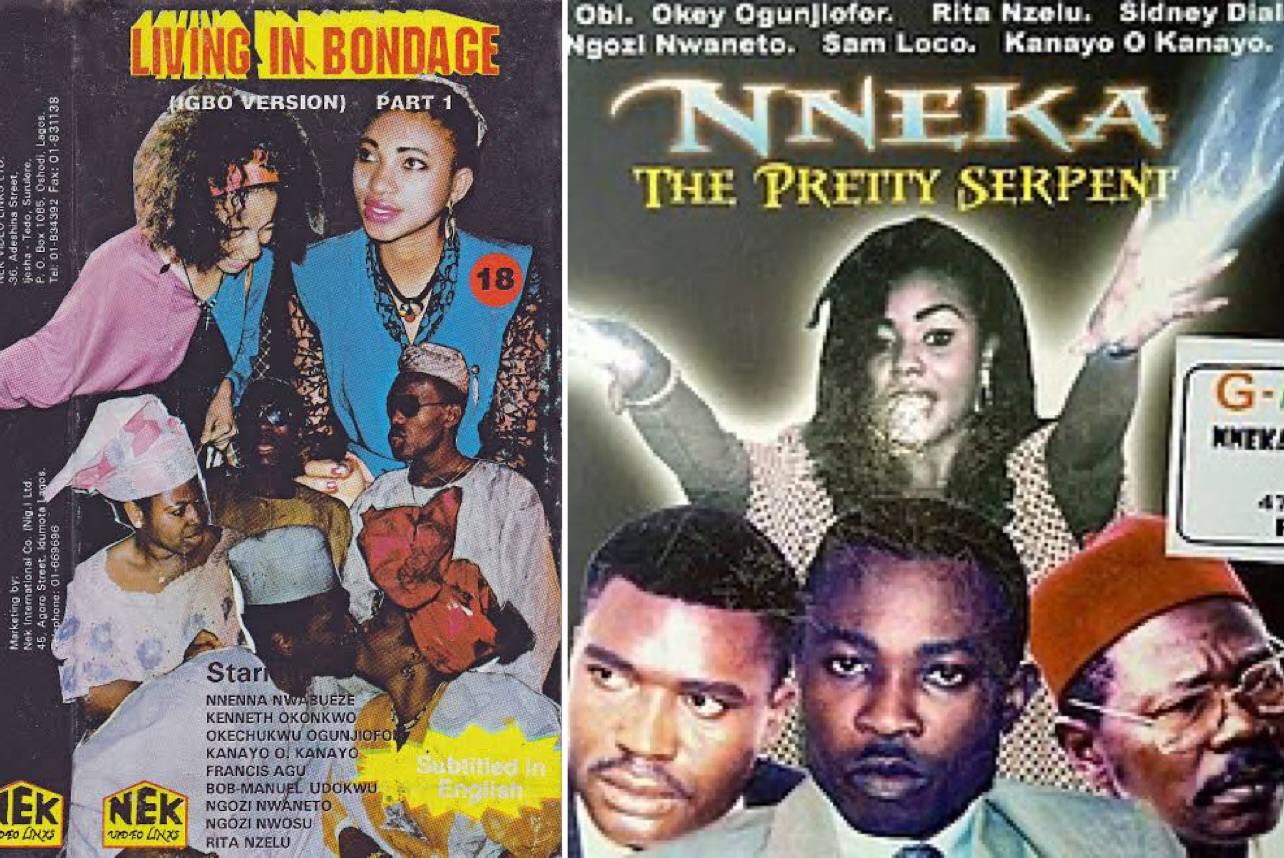

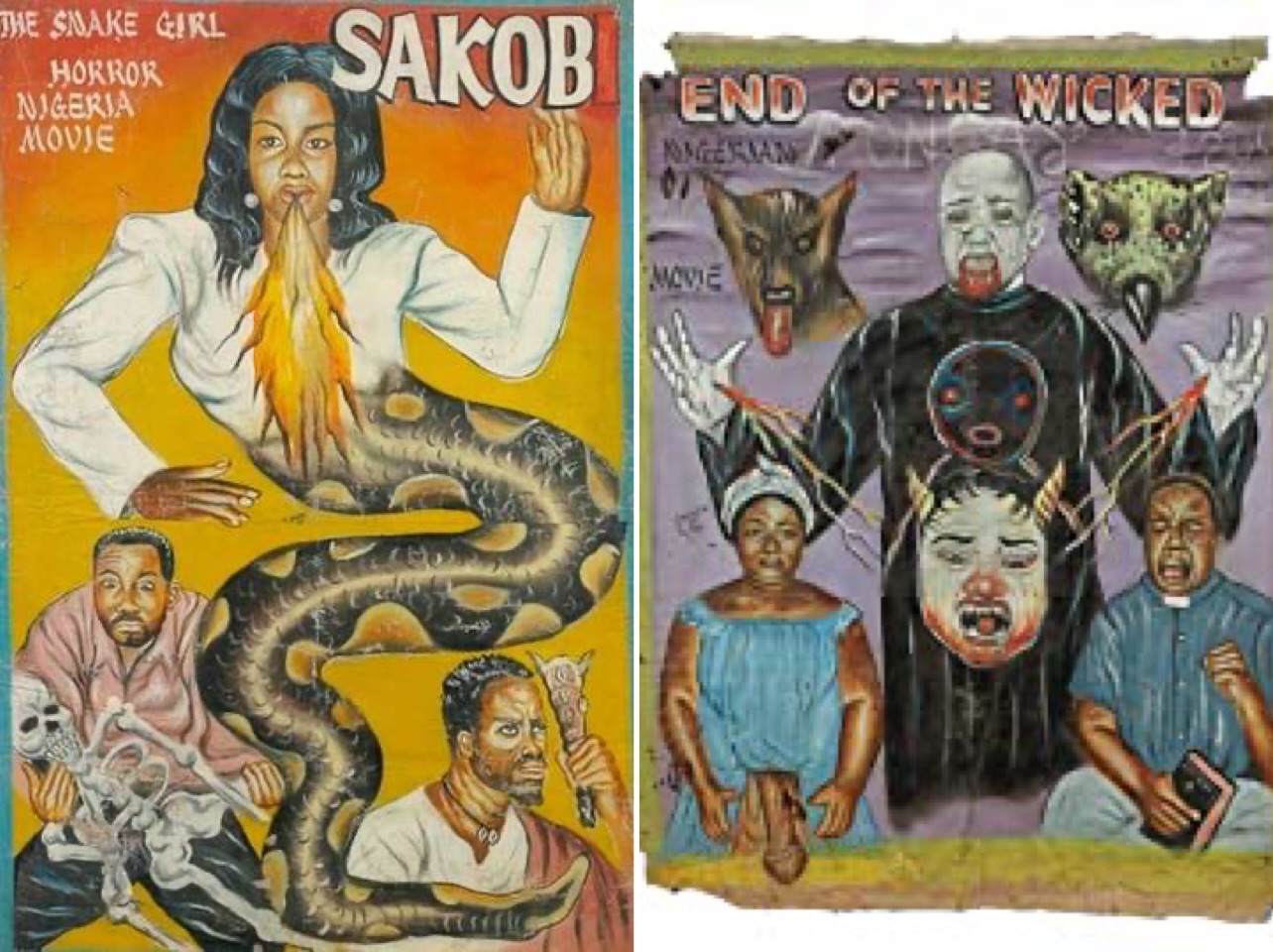

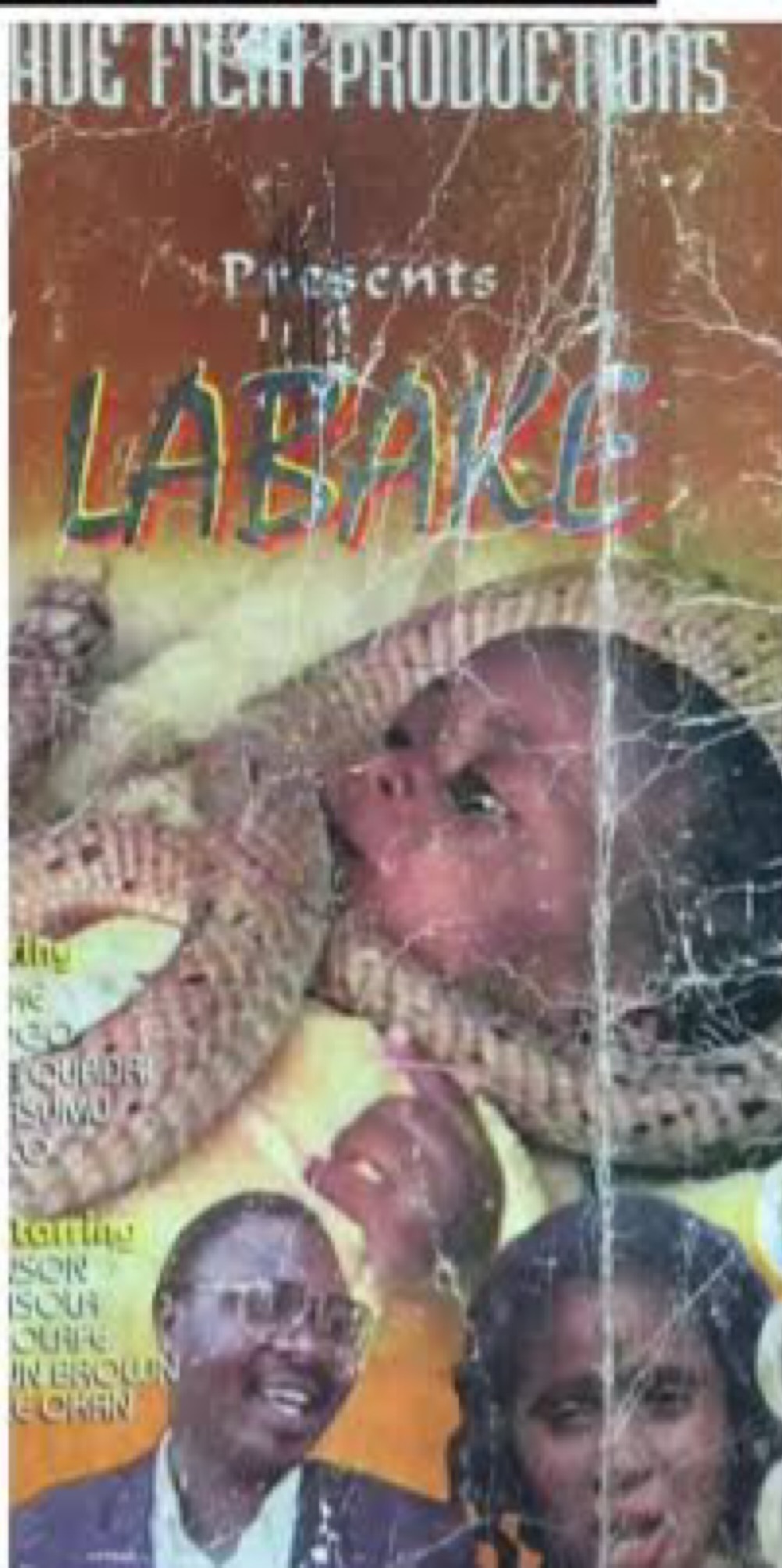

4. Embrace Bold Storytelling: Some of the scariest Nigerian horror of the past like End of the Wicked (1999) and Sakobi: The Snake Girl (1998) worked because they didn’t hold back. Today’s filmmakers can afford to be braver.

5. Train for the Craft: Horror is a technical genre. Workshops in sound design, lighting, VFX, and suspense writing could transform Nollywood horror into something global audiences respect.

Conclusoon

Once upon a time, Nollywood horror shaped childhoods and haunted dreams. From Kòtò Ayé and Làbáké Dejò to Nneka the Pretty Serpent, we had films that carried true cultural terror. Today, the genre has lost some of its bite, but not its potential.

If filmmakers can merge folklore with modern fears, polish with atmosphere, and bravery with craft, maybe one day Nigerian horror will make us turn off the lights and still regret it.