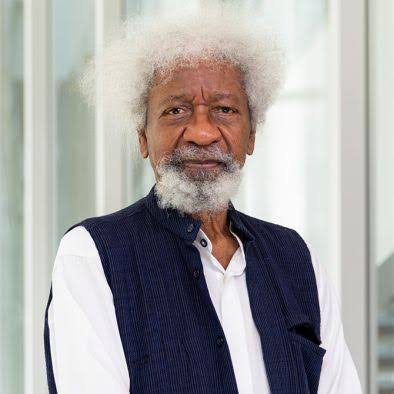

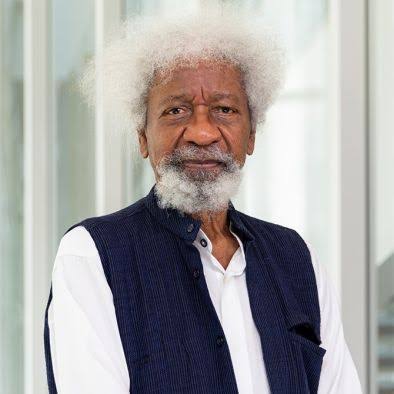

When Wole Soyinka earned the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1986, he became the first Black African laureate in that category—a writer whose art and life had already fused into a single dare: to speak truth to power and to insist that the classroom be a workshop for freedom rather than a chapel for silence.

- Beginnings: Ogun’s child in a colonial classroom

- Broadcasting dissent: The radio station affair

- Prison notes: Confronting the Generals of the civil war

- After the medal: The laureate as public conscience

- The Classroom Architect: “dictating” curricula by inventing them

- Craft and conviction: what the plays do

- The Nobel aftershocks: lectures, novels, and a restless elder

- A Pedagogy of courage

- Controversies and costs

- Influence that travels

- Reading list: where the truths live

- Curtain call: Why Soyinka still matters

Long before the medal, Soyinka had crossed lines many would not approach—seizing a radio station in the fevered 1960s, negotiating (and paying for) back-channel peace feelers as Nigeria slid into civil war, and, decades later, defying a military dictator from exile. Alongside that public defiance, he built theatre departments and syllabi that rearranged what “literature” could mean for a generation of students.

This is the story of a mind that staged its arguments, in lecture halls and on national stages and of a body that accepted the consequences.

Beginnings: Ogun’s child in a colonial classroom

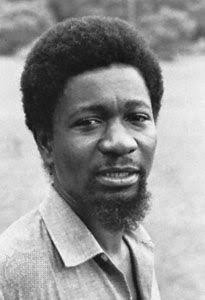

Born July 13, 1934, in Abeokuta, Western Nigeria, Akinwande Oluwole Babatunde Soyinka was raised between Anglican hymns and Yoruba cosmology. As a young man he studied at University College, Ibadan (1952–54), and continued at the University of Leeds, where the celebrated critic G. Wilson Knight supervised his work.

Those years in Britain, plus a formative stint at London’s Royal Court Theatre, gave Soyinka professional scaffolding without dimming the pull of home. He returned to Nigeria at the dawn of independence, determined to build institutions and repertories that would centre African dramaturgy on its own terms.

By 1960, while teaching at Nigerian universities, he founded the theatre troupes 1960 Masks and later the Orisun Theatre- vehicles for plays like A Dance of the Forests, The Trials of Brother Jero, and Kongi’s Harvest, which braided satire with ritual, and myth with modernity.

For Soyinka, Ogun, the Yoruba deity of iron, war, and creativity, was not merely subject matter but a dramaturgical principle: a fusion of danger and invention that would mark both his art and his activism.

Broadcasting dissent: The radio station affair

If Soyinka’s plays dramatized the ugly comedy of power, 1965 forced him into a far riskier performance. In the aftermath of a bitterly contested Western Region election, he walked into the Ibadan Broadcasting Corporation, allegedly at gunpoint, and forced staff to air an opposition message instead of the premier’s victory speech, a symbolic interruption of what many believed was a rigged process.

He was arrested and charged. A global chorus of writers protested. That December, a court acquitted him on a technicality. The case established a pattern that would repeat throughout his life: Soyinka the artist stepping into Soyinka the citizen when institutions faltered.

Prison notes: Confronting the Generals of the civil war

Two years later, as Nigeria descended toward civil war, Soyinka attempted a clandestine mission: meeting Biafran leader Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu to explore possibilities for peace. The federal government arrested him.

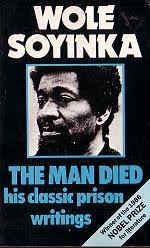

He spent 22 months in detention, much of it in solitary confinement, smuggling out essays and poems on scraps of paper that later became The Man Died: Prison Notes of Wole Soyinka. Those pages remain a classic of prison literature and a manual of interior defiance: make a world on a square of toilet paper if you must, but do not surrender the habit of meaning.

The physical toll was immense; the imaginative recomposition was greater. Prison consolidated Soyinka’s suspicion of absolute power—civilian or military—and intensified his belief that language, myth, and performance were not luxuries but ways to keep a society’s moral nerve alive.

After the medal: The laureate as public conscience

When the Swedish Academy honoured him in 1986 for a body of work that “in a wide cultural perspective and with poetic overtones fashions the drama of existence,” Soyinka used the platform to address the South African freedom struggle and the wider ethics of solidarity.

The medal didn’t tame him; it amplified him. In the late 1980s and 1990s, as Nigeria cycled through military regimes, Soyinka’s public essays and lectures, collected in books like The Open Sore of a Continent, cut through euphemism.

He opposed Ibrahim Babangida’s annulment of the 1993 election and later became a particular thorn in the side of Gen. Sani Abacha’s junta.

In March 1997, Abacha’s regime charged Soyinka with treason in absentia and threatened the death penalty. The charge sheet alleged complicity with bombings and political agitation through the pro-democracy coalition NADECO.

Soyinka, then in exile, refused to be cowed; the international press covered the case closely until Abacha’s death in 1998 dissolved the immediate danger. The episode locked in an image that had trailed him since 1965: the professor who would rather risk the scaffold than serve the comfort of tyrants.

The Classroom Architect: “dictating” curricula by inventing them

The headline’s second half“dictated classrooms” lands differently when you see Soyinka not as an autocrat of pedagogy but as its architect. He taught at the universities of Ibadan, Lagos, and Ife (now Obafemi Awolowo University), where he became Professor of Comparative Literature in 1975.

At Ife, he led the Department of Dramatic Arts and helped shape it into an intellectual commons that treated African performance traditions, not just Shakespeare and Sophocles, as foundational texts. Decades on, the department’s own history credits Soyinka with the leadership that solidified its identity during the late 1970s.

Soyinka himself has said, in a recent interview, that he transformed an initially practice-heavy School of Drama into a full Department of Theatre Arts, embedding research and critical theory into training without amputating the indigenous forms (music, masquerade, festival) that had always fed Nigerian performance. That curricular “dictation” mattered: it normalized African dramaturgies in the academy and licensed young artists to write—and think—from the centre of their own traditions.

The classroom was not his only civic institution. In 1988, the Babangida government created the Federal Road Safety Corps; Soyinka served as its inaugural board chairman, an unlikely but telling appointment. The dramatist built road-safety culture with the same mix of persuasion and provocation he brought to theatre, a wager that culture is policy, and policy is culture.

Craft and conviction: what the plays do

Satire as ethics. Early comedies like The Trials of Brother Jero lampoon the grift of self-anointed prophets; later satires, such as Madmen and Specialists, skewer the militarization of public life and the corrosion of language under dictatorship. Soyinka’s satire rarely targets single villains; it hunts systems, showing how greed, fear, and fatigue collude to make citizens tolerate the intolerable.

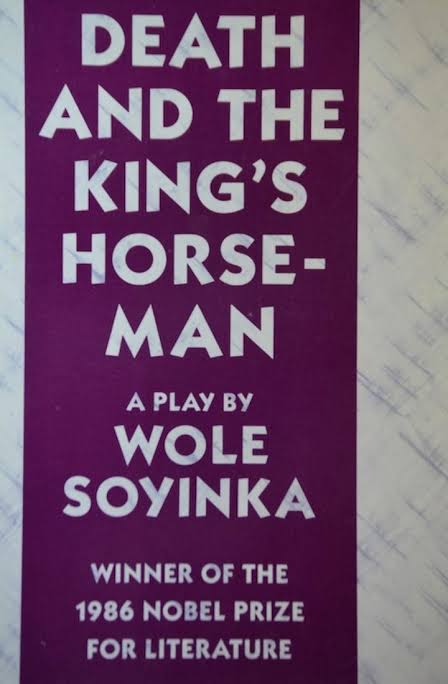

Ritual as dramatic engine. In Death and the King’s Horseman (1975), arguably his most studied play, Soyinka stages a ritual obligation—Elesin, the king’s horseman, must die to accompany his ruler into the afterworld—and the spiritual catastrophe when he fails.

Western readers often reduce the play to a “clash of cultures” between Yoruba tradition and British colonial officials who intervene, but Soyinka’s own framing resists that simplification; the play digs into duty, will, temptation, and metaphysical balance, with colonial interference as a crucial but not exhaustive factor. New productions and scholarship continue to revisit the play’s nuanced claim that a community’s cosmic grammar can be disrupted from within as much as from outside.

Theory beside theatre. Soyinka’s critical essays—including Myth, Literature and the African World—mounted an audacious argument in the 1970s: African literature should not be read as a derivative of Europe, nor as a museum of “traditions,” but as a living system with its own aesthetic laws. That insistence became a movable foundation for syllabi from Ibadan to the Ivy League.

The Nobel aftershocks: lectures, novels, and a restless elder

Far from retiring into laureateship, Soyinka spent the 2000s curating public arguments. His 2004 BBC Reith Lectures—later collected as Climate of Fear—considered terrorism, authoritarianism, and the paradox of liberation movements that calcify into the regimes they once opposed. The lectures feel prophetic now: a cartography of how fear rearranges private and public ethics.

In 2021, after nearly half a century away from the form, he returned to the novel with Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth, a scabrous satire of elite corruption and religious commodification. The late-career pivot reinforced an old truth: for Soyinka, genre is merely a different angle of approach to the same ethical weather.

A Pedagogy of courage

Talk to his former students and you hear a consistent refrain: Soyinka made the classroom feel like rehearsal for citizenship. His syllabi balanced Sophocles and Shakespeare with Yoruba oral poetry, masquerade aesthetics, and performance anthropology.

Assignments bled into productions; productions bled back into theory. The point wasn’t to “include” Africa in a European canon, but to reconfigure the canon’s geometry so students could stand at its centre and see outward. Departmental histories and interviews back this up: the Ife programme under Soyinka deliberately fused craft, criticism, and community engagement.

This pedagogy produced discomfort, sometimes outrage—the same emotional palette that his political interventions triggered. But then, education that never unsettles rarely liberates. Soyinka “dictated” classrooms in the sense that he insisted on a demanding seriousness: mastering forms, interrogating power, keeping language sharp and accountable.

Controversies and costs

Soyinka’s bluntness has also sparked criticism—from leaders he skewered, but also from activists and readers who disagree with some of his public positions. He has, for instance, been accused of elitism by certain critics; others contest specific interventions in Nigeria’s tempestuous political arena.

The record, however, is clear on the risks he accepted for his commitments—risks that include detention without trial (1967–69) and a treason charge that could have cost him his life (1997).

Even the famous 1965 radio incident remains contested in Nigerian public memory (as both folklore and political football), but the archival trail—from PEN case files to courtroom reports—confirms the essential outline and the subsequent acquittal.

What matters for understanding Soyinka is not only what happened but the imaginative logic behind it: when institutions are hijacked, art and action must improvise a counter-transmission.

Influence that travels

Soyinka’s influence travels along at least three channels:

1. Institution-building. Departments he shaped at Ibadan and Ife produced writers, directors, and scholars who, in turn, built programmes across Africa and the diaspora. That infrastructure—festivals, journals, degree programmes—outlasts any single production.

2. A canon with African gravity. His essays helped an entire generation read African texts with African conceptual tools, rather than apologizing for them to European standards. He didn’t reject cross-cultural dialogue; he demanded reciprocity.

3. Civic imagination. As inaugural board chair of the Federal Road Safety Corps, Soyinka made an unlikely point: that culture saves lives not only metaphorically; it writes traffic codes, trains officers, and dignifies public space. That’s not a side note; it’s his artistic ethic wearing a reflective vest.

Reading list: where the truths live

If you want to grasp the full Soyinka—artist, teacher, activist—start here:

Memoir: The Man Died (1972) — the prison diary that shows writing as survival.

Criticism: Myth, Literature and the African World (1976/78) — essays that reframe the terms of African aesthetics.

Drama: Death and the King’s Horseman (1975) — ritual, duty, and colonial meddling; best read alongside critical commentary and Soyinka’s own author’s note.

Public Lectures: Climate of Fear (from the 2004 Reith Lectures) — on terror, freedom, and the ethics of resistance.

Recent fiction: Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth (2021) — a late-style satire whose targets feel depressingly current.

Curtain call: Why Soyinka still matters

To say Soyinka “confronted generals and dictated classrooms” is, in one sense, accurate. But it misses the heart of his project. He confronted generals because he thinks power should fear citizens who can imagine alternatives. He “dictated” classrooms only insofar as he demanded rigor and insisted that African thought be taught as a sovereign archive, not an appendix.

The result is a 70-year experiment in freedom: theatre that won’t flatter its audience, essays that won’t flatter their allies, and a pedagogy that refuses to flatter the canon.

Whether you meet him in a prison note, a lecture hall, or the charged silence before Elesin’s drumbeat, Soyinka makes the same demand: be brave; think harder; don’t outsource your conscience.