Lagos in 1993 did not sleep easily. The city was loud, restless, vibrating like a drum stretched too tight. Taxi horns blared through Marina, market women haggled in Mushin, and the smell of roasted corn mixed with exhaust fumes hung over Ojuelegba bridge.

- The Boy Who Dreamed Beyond Abeokuta

- King Sunny Ade: The Musician Who Spoke for a People

- Campaigns as Carnivals

- June 12: The People’s Election

- When the Music Turned to Mourning

- Politics, Music, and Yoruba Tradition

- Legacy: Music in Politics After MKO

- Conclusion – The President Who Was Sung but Never Crowned

Beneath the ordinary noise of a megacity, another sound pulsed—anxious whispers about a coming election that might change everything. Nigeria had seen ballots before, but this one felt different. Hope was in the air, fragile yet undeniable, like the scent of rain before a storm.

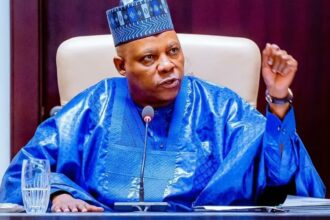

In that season of uncertainty, one man’s name traveled like song: Moshood Kashimawo Olawale Abiola—MKO. He was, for the first time, the presidential candidate who seemed to belong to everyone—north and south, Christian and Muslim, poor and rich.

This is the story of how MKO Abiola, the man Nigeria chose but never crowned, used the cultural power of King Sunny Ade’s music to win the streets, and how those songs became both memory and mourning when the dream of June 12 was stolen.

The Boy Who Dreamed Beyond Abeokuta

Abeokuta in the late 1930s was no city of riches. It was a town defined by its rocks—ancient stones that bore witness to the Egba people’s wars, trade, and survival. Into this soil, on August 24, 1937, a boy was born to a family so poor that they named him Kashimawo—“let us wait and see.” Too many children had died before him; his survival was not taken for granted.

Little Moshood sold firewood, carried water, and hawked kola nuts just to help his parents make ends meet. He went to school barefoot while his classmates wore shoes. Yet he carried within him a stubborn hunger, not just for survival but for greatness. At Baptist Boys’ High School, he excelled in mathematics, debate, and music. He could recite Yoruba proverbs with precision and lead songs with a charisma that pulled others in.

That charisma would never leave him. After studying accounting in Scotland, he returned home and began a career with ITT, rising so quickly through the company’s ranks that he soon owned a major stake. By the 1980s, Abiola was among Africa’s wealthiest men, with businesses in oil, banking, publishing, and telecommunications. But unlike other moguls, he gave generously. He built schools and mosques, paid dowries for poor families, sent strangers’ children abroad, and funded football clubs.

In Yoruba culture, wealth is not respected unless it circulates. Abiola understood this perfectly. He became known as a man of the people—arugbo ojo, the patron whose hands never stayed closed. By the time he declared for the presidency under the Social Democratic Party (SDP), Nigerians across divides already knew his name not from politics, but from their own lives. He was the man who had paid their cousin’s tuition, repaired their local mosque, or sent fertilizer to their village farm.

But generosity alone could not electrify the streets. Nigeria was weary of politicians who gave during campaigns and vanished afterward. To capture not just loyalty but passion, Abiola needed something else. He needed music.

King Sunny Ade: The Musician Who Spoke for a People

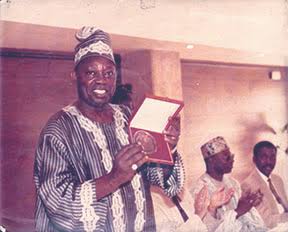

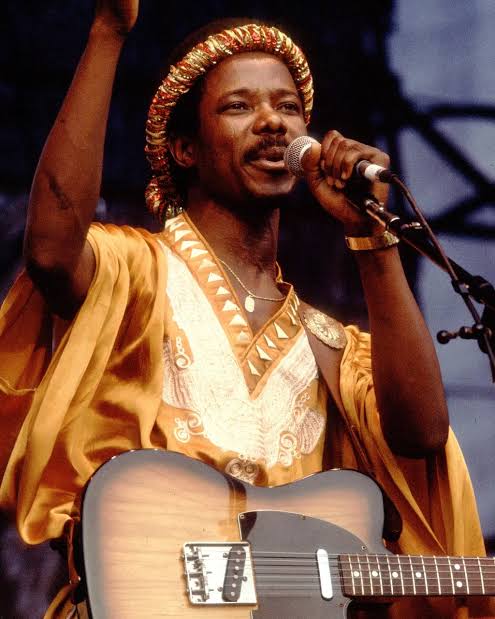

By the early 1990s, King Sunny Ade was no ordinary musician—he was a living institution. His juju music had conquered dance halls in Lagos, Ibadan, and beyond. His talking drums mimicked the tones of Yoruba language, turning rhythm into speech. His guitar wept, laughed, and sighed in the same breath, while his sprawling band created a sound that was both modern and deeply traditional.

Sunny Ade had already carried Yoruba music to the world stage. In 1982, he signed with Island Records, the same label that had turned Bob Marley into a global icon. His albums introduced juju to audiences in America and Europe, but at home, his power was far greater than commercial. In Yoruba society, musicians are more than entertainers; they are custodians of memory, heralds of lineage, and shapers of reputation. A well-placed praise song could elevate a man’s status; a biting lyric could tarnish it.

Politicians had long courted musicians, but Sunny Ade’s involvement with MKO was unique. This was not mere endorsement—it was immersion. Sunny Ade’s music became the campaign’s heartbeat, turning rallies into festivals where policy blurred into performance.

Campaigns as Carnivals

Picture Ibadan, 1993. The Mapo Hall square is overflowing. Traders leave their stalls, okada riders park their bikes, women tie gele tighter as they sway toward the rally grounds. The stage is set, banners fly, but before MKO appears, music takes over.

Sunny Ade’s band erupts—guitars shimmer like Lagos sunlight on tin roofs, drums converse with each other in Yoruba idioms, and dancers twirl, their sequins catching the afternoon light.

Then comes the moment. Sunny Ade calls Abiola’s name mid-song, folding it into melody as though it had always belonged there: “M-K-O, hope ‘93!” The crowd roars. For the Yoruba, to be named in song is to be blessed, immortalized. For Abiola, it was legitimacy, cultural coronation.

From Kano to Port Harcourt, the script repeated. MKO’s rallies were not dry lectures—they were weddings without brides, carnivals without endings. Children sang the jingles, market women danced, taxi drivers played campaign tapes on repeat. Opposition candidates spoke of policies; Abiola offered performance. He understood instinctively that in a country where literacy was uneven but rhythm was universal, music was the surest way to win the street.

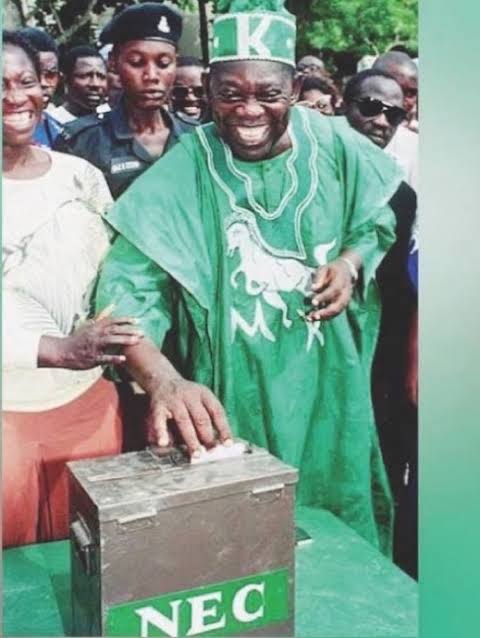

June 12: The People’s Election

On June 12, 1993, Nigerians went to the polls with unusual calm. In Kano, Hausa women lined up to vote for a southern Muslim candidate. In Enugu, Christians cast ballots for a man who had built churches alongside mosques. The election was hailed as the freest and fairest in Nigeria’s history.

Abiola’s victory was sweeping. He won across ethnic and religious divides, something no Nigerian leader had managed before. For once, the nation seemed united under a single choice. On the streets, people hummed campaign songs even after casting their votes, as though the music itself had guaranteed victory.

But joy turned quickly to betrayal. General Ibrahim Babangida annulled the election, plunging Nigeria into political crisis. The same streets that had danced to Sunny Ade’s rhythms now erupted in anger. Protesters chanted Abiola’s name, some setting his campaign songs to new, defiant lyrics.

When the Music Turned to Mourning

The annulment scarred Nigeria. Abiola declared himself president and was later arrested. His detention became a symbol of stolen democracy. Across Lagos, musicians who had once sung in praise turned to lamentation. Sunny Ade himself retreated into careful neutrality, while Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, the Afrobeat firebrand, sharpened his attacks on the military.

Yet the memory of those campaign songs lingered. For many, they became bittersweet reminders of a Nigeria that could have been—a country where democracy arrived with music instead of guns. Abiola’s name, once sung in praise, became elegy. When he died mysteriously in prison in 1998, the streets wept, and for days, it was music again—dirges, drums, and church hymns—that carried the nation’s grief.

Politics, Music, and Yoruba Tradition

Why did music matter so deeply in MKO’s rise? The answer lies in Yoruba tradition. Leadership in Yoruba society has always been performed as much as exercised. Kings are crowned not only with crowns but with drums and songs. Praise-singers (oriki) immortalize rulers by reciting their lineages, while drummers speak names into rhythm.

By aligning with Sunny Ade, Abiola tapped into this tradition at scale. He was not just a candidate; he was a man sung into authority. In Yoruba metaphysics, what is sung exists. Abiola’s campaign transformed politics into collective ritual, where dancing together meant believing together.

The song “Chief M.K.O. Abiola” was composed by King Sunny Ade to honor Abiola’s candidacy and his symbolic role in Nigeria’s democratic struggle. This track became a central anthem during the campaign, resonating deeply with supporters and the general public.

The song’s lyrics celebrated Abiola’s leadership and vision, and its upbeat, celebratory style helped energize rallies and gatherings. Its popularity was such that it was later included in King Sunny Ade’s 1992 album Surprise, further cementing its association with the campaign.

For a glimpse into the song’s impact, you can listen to “Chief M.K.O. Abiola” on platforms like Spotify and SoundCloud.

Legacy: Music in Politics After MKO

After 1993, no Nigerian politician ignored music again. Obasanjo’s campaigns courted Fuji stars. Jonathan’s rallies featured Nollywood entertainers. Buhari leaned on northern praise-singers, while contemporary candidates hire Afrobeats artists like D’banj, Olamide to energize crowds.

Yet none have matched Abiola’s fusion with Sunny Ade. For MKO, music was not accessory—it was essence. His campaign remains the model of how to translate wealth into cultural belonging, and how rhythm can achieve what rhetoric cannot.

Conclusion – The President Who Was Sung but Never Crowned

MKO Abiola never sat in Aso Rock. His victory was stolen by generals, his life cut short in detention. Yet in the memories of millions, he remains the president they chose. And they remember him not through policy documents or economic blueprints, but through the songs that carried his name.

When Sunny Ade’s guitars shimmered and the talking drum echoed “M-K-O,” it was as though democracy itself was dancing. That dance was interrupted, but the rhythm never died. Even today, three decades later, when Nigerians speak of June 12, they do not just recall votes cast or elections annulled—they recall the music, the hope, and the fleeting moment when politics and song became one.

Because politics may silence a man. But music—once released into the air—never dies.