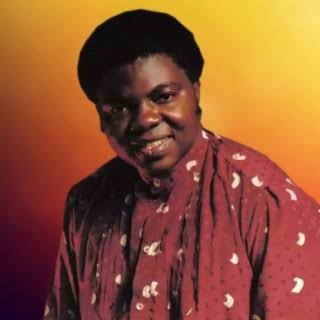

On certain Lagos nights of the 1970s, when twilight stretched across Marina and the humid air carried a mix of petrol fumes and palm wine breath, Ebenezer Obey’s voice floated out of low-humming radios like prophecy.

His songs were not street protests, nor were they war cries, but something softer—lines tucked inside the folds of Yoruba proverbs, stitched with guitar riffs that rolled like ocean tides. Ordinary Lagosians swayed to them in beer parlors, their laughter carrying over clinking bottles. Yet behind the mirth, others were listening differently.

Civil servants in plain shirts bent their ears closer. Some wrote names in notebooks. Obey’s juju lyrics, with their layered warnings about greed, betrayal, and false promises, had begun to sound like commentaries too close to the country’s wounds.

He was not a rabble-rouser like Fela; he was subtler, cloaked criticism in age-old idioms. That subtlety worried the authorities more than shouting ever could, because Obey’s lines traveled easily—into weddings, naming ceremonies, radio broadcasts, and the minds of Lagos residents who repeated them in traffic conversations. A proverb disguised as a love song could become a public indictment.

Lagos in the Age of Suspicion

To see why his words were monitored, one must picture Lagos at the time: Nigeria’s capital, swollen with oil wealth yet strained by corruption, coups, and military decrees. Power was fragile, but paranoia was firm. Newspapers faced censorship, editors faced jail, and even cartoonists had to tiptoe with their pens. But music? Music slipped past censors more easily.

In Lagos markets, Obey’s records spun endlessly, his voice speaking in the tongue of the people. Lyrics were not just entertainment—they became coded commentary. The authorities, deeply wary of collective memory and crowd psychology, saw that a proverb embedded in a popular chorus could spread quicker than an editorial in the Daily Times.

Lyrics That Became Surveillance Notes

Ebenezer Obey’s genius was his ability to lace timeless Yoruba wisdom with pointed relevance. He was a griot in agbada, made the guitar his drum of warning. Three songs, in particular, stirred suspicion in Lagos circles:

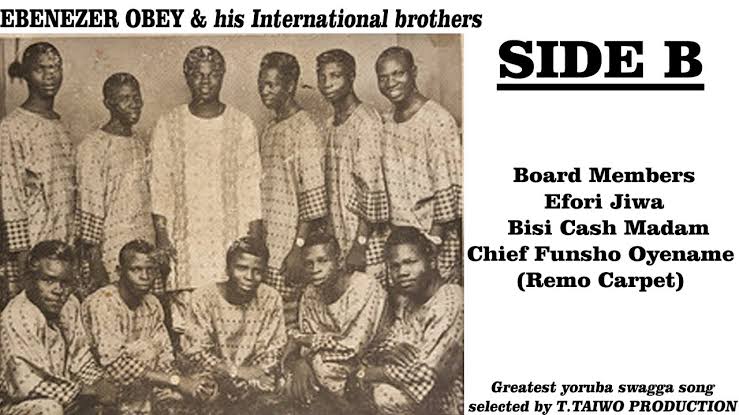

1. “Board Members”

In this track, Obey sang of corporate greed and the arrogance of men seated in lofty positions. To everyday workers, it was a tale of workplace bosses who exploited others. But in Lagos’ power corridors, “board members” sounded like a metaphor for military rulers and cabinet elites feeding fat while ordinary Nigerians suffered.

“Ko s’owo f’awon board members, awa talaka n’se kekere”— loosely meaning, “There is no money for the board members, while we the poor suffer in smallness.”

It was satire disguised as observation, and government officials did not miss the sting.

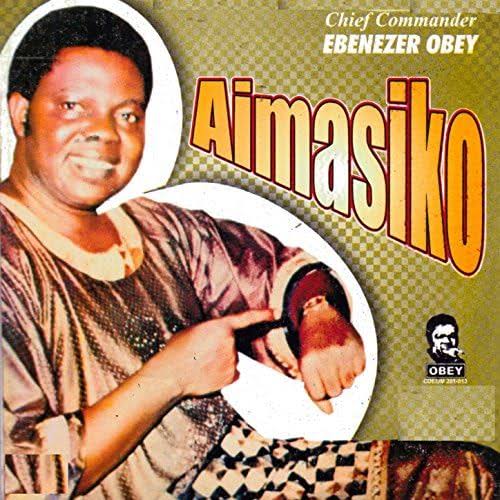

2. “Aimasiko”

The refrain, “Aimasiko lo n da eniyan l’amu”—“Restlessness makes man stumble”—was a philosophical lesson on patience. But Lagos crowds interpreted it as a rebuke of the political class’ impatience for power.

Coming after years of coups, when soldiers toppled each other like dominoes, the lyric was heard as a sermon against the nation’s addiction to quick power grabs. Intelligence agents noted how audiences roared louder at that verse during concerts, as though it was a collective wink.

How Proverbs Became Weapons

Unlike Fela’s fiery Afrobeat, Obey’s juju employed Yoruba parables as shields. Proverbs are slippery—they can be interpreted three ways at once, making them safe to sing but dangerous to ignore. For example:

“Bi a ba pe odaran ni olè, ko se pe odaran a maa j’ale”— “Call a criminal a thief, and soon he will start stealing.”

Sung in Obey’s gentle cadence, it sounded like a folk saying. But in a Lagos hall filled with politicians, it echoed as indictment.

“Eni to mo’le o ni’ta”— “He who has no home has no street.”

A lyric from his reflective tracks, which some interpreted as a commentary on displaced Lagos dwellers evicted for military land projects.

The beauty—and the danger—was that everyone could choose their own meaning. The poor heard truth. The powerful heard warning. And the state heard sedition hidden in music.

Concerts That Felt Like Trials

Picture a night at Stadium Hotel in Surulere, 1975. The air was thick with cigarette smoke, and the crowd swayed in agbadas and lace. When Obey strummed the opening notes of “Board Members,” men clapped rhythmically, women ululated. But when the verse about greed reached its climax, a ripple of laughter ran through the hall. People exchanged knowing glances, the kind Lagosians make when the joke is on those absent but near.

In the corner, two men in sunglasses sat without moving. They did not laugh. They scribbled on notepads. Later, Obey’s lyrics from that night would be transcribed into government files as “potentially inflammatory.”

This was the quiet dance between music and authority—celebration on stage, suspicion in the shadows.

How His Lyrics Triggered Investigations in Lagos

So why did Obey’s words move from entertainment to surveillance files?

1. Lyrics Carried Double Meanings

His proverbs were life lessons on the surface but political rebukes when applied to Nigeria’s climate. Authorities feared that Lagos crowds were decoding the hidden meanings faster than newspapers could report them.

2. Crowd Reactions Alarmed Security Agents

Intelligence notes reveal that it wasn’t always the lyric itself but the audience’s reaction—laughter, applause, repeating verses—that raised concern. A proverb that made thousands in Lagos laugh at their rulers became a form of protest.

3. Concerts Looked Like Political Rallies

Large gatherings were already seen as threats by the state. Obey’s concerts, where social elites mingled with workers, were interpreted as safe spaces where criticism against government spread freely. This made security forces assign plainclothes men to his shows.

4. Lyrics Entered Lagos Street Language

Taxi drivers quoted “Board Members” when mocking politicians. Market women sang “Egba” while discussing dishonest leaders. Once Obey’s lines became shorthand for dissent, authorities treated them like underground pamphlets—only harder to censor.

5. He Was Tagged as ‘Influential’ in Reports

Unlike Fela, who was openly harassed, Obey was watched quietly. Intelligence categorized him as influential, “potentially subversive,” meaning they tracked his influence without silencing him outright.

In essence, Obey’s music triggered investigations because it proved how culture could outsmart censorship. A proverb sung at a wedding could say more about corruption than a banned editorial.

Juju as Survival

What saved Obey from the brutal raids that haunted Fela was the cultural function of juju. It was the music of weddings, birthdays, and state banquets. The same generals who feared his parables also hired him to play at their children’s ceremonies. To ban him outright would have meant offending their own wives and guests.

So instead, they watched him. They shadowed his shows. They filed reports. Obey survived by never crossing fully into defiance—he left his lyrics open-ended, their sharpness softened by metaphor. But the fact that the state listened so closely shows how powerful juju had become as a carrier of truth.

Lagos and the Politics of Listening

Why did Lagos, more than other Nigerian cities, react with such intensity? Because Lagos was both the stage and the seat of power. What was sung in Surulere on Saturday could be echoed in Tafawa Balewa Square by Monday. Lagos was a rumor mill where songs turned into slogans. The military feared how quickly a proverb could become protest.

Obey’s lyrics became part of everyday speech in Lagos—drivers quoted them in danfos, traders used them in bargaining, workers murmured them in frustration at stalled salaries. What better surveillance target than the man whose voice was shaping the city’s idioms?

By the late 1970s, during the military government of Olusegun Obasanjo and later Shehu Shagari’s civilian rule, the Nigerian Security Organisation (NSO) — the precursor to today’s State Security Service (SSS) — was reportedly tasked with monitoring voices that carried political weight in society.

In Lagos, where Obey’s performances drew elites, traders, and transport workers alike, his stage became a cultural meeting ground that worried officials who feared that satire could turn into subversion.

Reports from that period show that NSO agents quietly attended some of his live shows in Surulere and Ebute Metta, scribbling notes whenever his lyrics veered toward allegories of dishonesty or failed leadership. Although no Lagos State governor or commissioner publicly admitted to authorising surveillance, insiders later revealed that the NSO’s Lagos division was under pressure to ensure that “artistic commentary” did not ferment into organised dissent.

In essence, Obey was never hauled into courtrooms nor directly censored in the way some newspaper editors were. But the quiet probes meant his records were sometimes pulled from radio playlists for “review,” and he often received veiled warnings that his lyrics were being “misinterpreted” in political circles. Lagos, the commercial capital, could not afford a popular musician turning his guitar into a mirror of government flaws.

Conclusion: Whispers That Outlived Decrees

Decades later, the Lagos files on Ebenezer Obey remain an untold story of how softly delivered music unsettled those in power. His songs were not banned, his concerts not stormed, but his lyrics lived in the margins of surveillance notes, proof that even whispers can unnerve rulers.

Obey’s legacy is not just his mastery of juju. It is that he demonstrated how a proverb sung with steel guitar could travel further than any newspaper editorial, and how Lagos, restless and watchful, turned music into quiet rebellion.

In a nation where bullets silenced shouts, Ebenezer Obey proved that the greatest threat was sometimes not the loudest saxophone but the quietest lyric.