In the quiet corners of literary history, some voices linger longer than the pages they wrote. Chinua Achebe’s voice is one of them — precise, measured, yet resonant, echoing across decades of African storytelling. When filmmakers first sought to translate his words into images, they encountered a challenge both simple and profound: how do you capture not just a story, but the pulse of a culture, the cadence of a civilization, and the invisible threads that connect people to their history?

- Achebe’s Biography — The Source of the Story

- Nollywood’s First Attempt: The 1987 NTA Adaptation

- The Supporting Cast and Nollywood’s Learning Curve

- Why Achebe’s Biography Matters to Nollywood’s Adaptation

- Between Fidelity and Flaws

- What Achebe Said — And Didn’t Say

- Achebe’s Death and the Unfinished Conversation

- Idris Elba and the Global Stakes

- Conclusion: The River Still Flows

Cinema, with all its lights and cameras, promises spectacle, yet it often stumbles over subtlety. Achebe, ever vigilant, watched the first attempts from a distance, offering measured critique, but leaving much unsaid. His silence, deliberate or unavoidable, became a mirror — reflecting the tensions between artistic ambition and cultural fidelity, between global interest and local voice.

Years later, as Nollywood rose and the world’s attention shifted to African screens, these tensions deepened. What does it mean to interpret a canonical work of literature in a society still negotiating identity, memory, and representation? What does it mean when the world begins to stake claim over stories that are intimately local, deeply rooted, and historically complex?

This article follows those echoes — the words Achebe spoke, the critiques he withheld, and the cinematic reflections of a work that has resisted being confined. It is a journey into the delicate balance between adaptation and authenticity, and into the spaces where what is left unsaid speaks as loudly as what is spoken.

Achebe’s Biography — The Source of the Story

To understand what Achebe said—and didn’t say—about Nollywood’s Things Fall Apart, we must first return to the soil from which he himself was formed. Every writer is both a product of their environment and a critic of it, and in Achebe’s case, the environment was not merely geographical; it was cultural, spiritual, and historical.

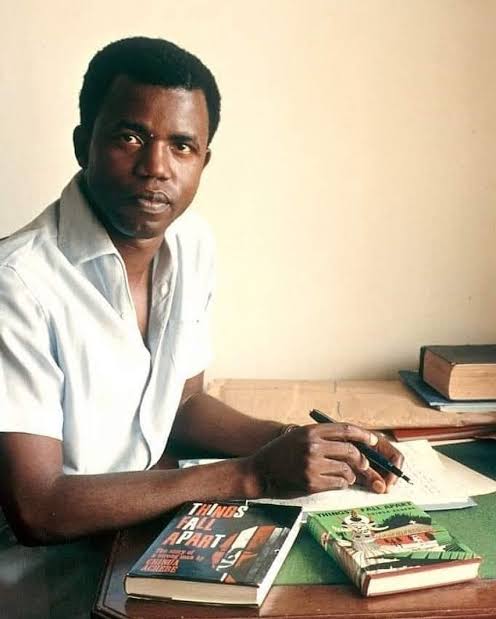

1) Early Life in Ogidi: Between Two Worlds

Albert Chinualumogu Achebe was born on November 16, 1930, in Ogidi, a town in present-day Anambra State, southeastern Nigeria. His birthplace was more than a setting—it was a crucible of contrasts. Achebe’s father, Isaiah Okafo Achebe, was a devout Christian convert and a catechist with the Church Missionary Society. His mother, Janet Anaenechi, came from a family steeped in Igbo traditions and was known for her skill as a storyteller.

Thus, from infancy, Achebe straddled two worlds: the structured discipline of Christian modernity and the lyrical, communal rhythm of Igbo oral culture. His home was filled with biblical parables and church hymns, yet equally saturated with folktales, proverbs, and ancestral lore. Where some children grow up learning only one language of meaning, Achebe grew up bilingual in the spiritual sense—fluent in both the language of scripture and the idioms of oral tradition.

This dual inheritance would later define his work: a writer rooted in African soil, yet fully aware of the lenses through which outsiders viewed his people.

II) Education and the Awakening of a Writer

Achebe’s academic journey began at Government College, Umuahia, a school that would later produce some of Nigeria’s finest literary minds. There he encountered the English literary canon—Shakespeare, Milton, Dickens—but also the troubling distortions of Africa presented in colonial texts. Books such as Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness portrayed the continent as a void, a mere backdrop for European adventure. Achebe read these works not passively, but critically, recognizing the deep misrepresentation at play.

At University College Ibadan, where he studied English, History, and Theology, Achebe’s sense of purpose sharpened. He began to question why African voices were absent from the global literary conversation, why African life was consistently filtered through European prejudice. It was here that the seeds of Things Fall Apart were planted—not merely as a story to be told, but as a counter-narrative, a reclamation of agency.

III) Broadcaster, Teacher, Editor: The Shaping of Perspective

Before becoming the global literary figure we know, Achebe worked as a broadcaster for the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation. The experience refined his sense of audience, pacing, and clarity. Radio demanded immediacy and accessibility, qualities that would later define his prose style. He also worked as an editor, championing the voices of other African writers and creating platforms for emerging talents.

Achebe was not just a novelist; he was an architect of African literature’s public sphere. By the time Things Fall Apart was published in 1958, he was already positioned not only as a writer but as a cultural custodian, aware of the power of stories to shape both identity and perception.

IV) Achebe’s Literary Philosophy

Achebe’s commitment to authenticity was evident not only in his writing but also in his views on cultural representation. He believed that African stories should be told by Africans, in their own voices, and in their own languages. This philosophy extended to the realm of film adaptations. In 1971, a film adaptation of Things Fall Apart was produced by joint Nigerian, German, and American production, directed by Hans Jürgen Pohland, but Achebe was reportedly dissatisfied with the result, felt that it misrepresented the nuances of his novel.

This historical context is crucial when considering the current adaptation. Achebe’s legacy is built upon a foundation of cultural pride and authenticity. Any adaptation of his work must navigate these waters carefully, respecting the integrity of the original while exploring new creative avenues.

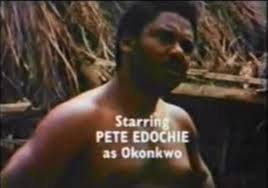

Nollywood’s First Attempt: The 1987 NTA Adaptation

Before Nollywood exploded into the global phenomenon it is today, there was the 1987 Nigerian Television Authority (NTA) adaptation of Things Fall Apart. At a time when Nigeria’s economy was struggling and the television industry was stretched thin, this adaptation carried more symbolism than spectacle. Its strength lay not in special effects or grand budgets, but in cultural ownership: it was a Nigerian book, adapted for Nigerians, by Nigerians.

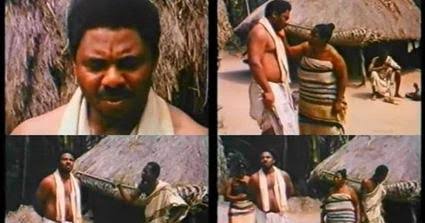

At the heart of this production was Pete Edochie, cast as Okonkwo. His performance was a revelation. With his broad frame, thunderous voice, and piercing gaze, Edochie didn’t just act Okonkwo; he inhabited him. His clenched jaw, deliberate pauses, and sudden bursts of fury captured both the strength and the brittleness Achebe had woven into the character. Many Nigerians who watched the adaptation in 1987 later confessed that they could no longer read Things Fall Apart without hearing Edochie’s baritone echoing Achebe’s prose.

Edochie’s Okonkwo quickly became a cultural benchmark. His portrayal was so convincing that it birthed an archetype within Nollywood itself. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, countless Nollywood films recycled variations of his character — the stern father, the unyielding patriarch, the traditionalist caught between worlds. Achebe’s tragic hero had been reduced, in part, to a Nollywood stock character. This was both a tribute and a distortion.

The Supporting Cast and Nollywood’s Learning Curve

Though Edochie dominated, the adaptation was more than just one man. The supporting cast played crucial roles in introducing Achebe’s Igbo society to a generation that had not lived it directly. Characters like Obierika, Okonkwo’s thoughtful friend, were embodied with quieter gravitas, offering viewers an alternative to Okonkwo’s intensity. Female characters, though constrained by the production’s resources, gave life to the domestic and communal rhythms Achebe had so carefully documented.

But here Nollywood stumbled. The sets were modest, the costumes sometimes improvised, and the cinematography limited by the technology of the time. Achebe’s prose painted villages that pulsed with texture — the rustle of palm fronds, the solemnity of rituals, the crowded energy of marketplaces. The adaptation, though sincere, could not always deliver that richness. It sometimes reduced the world of Things Fall Apart to functional backdrops, missing the immersive detail Achebe had intended.

Still, it mattered. For the first time, millions of Nigerians saw Achebe’s novel on screen, in their own accents, in settings that felt like extensions of their own communities. It gave Nollywood — still nascent — a foundation. It declared: we can adapt our stories ourselves, without waiting for Western validation.

Why Achebe’s Biography Matters to Nollywood’s Adaptation

The story of Achebe’s life is not incidental to Nollywood’s engagement with Things Fall Apart. His upbringing in dual traditions, his education in colonial and indigenous knowledge systems, and his philosophy of cultural responsibility shaped what he considered authentic storytelling.

When Nollywood attempted to translate his work to screen, they were not merely adapting a novel. They were stepping into the legacy of a man who saw stories as guardians of cultural identity. His silences, his rare words of encouragement, and his refusal to reduce his work to spectacle all flowed from this deeper biography.

To misunderstand Achebe the man is to misunderstand Achebe the novelist—and, by extension, to misunderstand the responsibilities of adapting his work.

Between Fidelity and Flaws

The strength of Nollywood’s Things Fall Apart lay in its fidelity to Achebe’s storyline. Unlike many Nollywood productions of the 1990s, which improvised wildly on source material, the NTA adaptation tried to follow Achebe’s structure closely. But fidelity did not always translate to depth.

Achebe’s novel thrives on ambiguity — Okonkwo is not simply a “strong man” but also a man undone by fear, insecurity, and cultural shifts. Nollywood, in its first attempt, sometimes leaned too heavily on the surface traits: Okonkwo as the angry, domineering patriarch. Subtler layers — his quiet moments of doubt, his symbolic unraveling — were harder to capture within the limited screen format.

This tension between fidelity and flaw would become a hallmark of Nollywood adaptations. The industry excelled at dramatization but struggled with nuance. Achebe’s silences, his careful pacing, his refusal to moralize — these were qualities Nollywood often had little patience for. The result was a partial translation: powerful in presence, limited in interpretation.

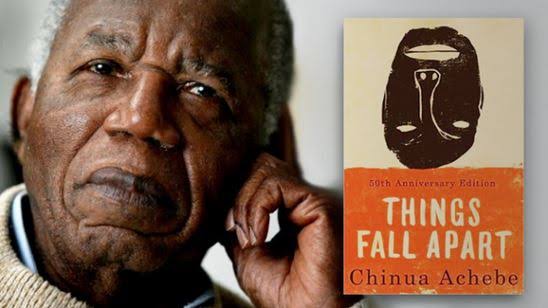

What Achebe Said — And Didn’t Say

Achebe himself never offered a detailed public commentary on the NTA adaptation or Nollywood’s later echoes of his work. What he did say, in various essays and interviews, was revealing in other ways. He spoke often about the importance of narrative ownership, about Africans telling their own stories without distortion. In Morning Yet on Creation Day (1975), he warned against the dangers of misrepresentation in popular media.

But he never set down rules for film. Achebe, a man of the written word, seemed content to let cinema do what it could, even if imperfectly. This silence was strategic. Had he condemned Nollywood, he might have stifled a growing industry that desperately needed legitimacy. Had he endorsed it, he might have bound his legacy to productions he could not control. By saying little, Achebe left Nollywood with freedom — and responsibility.

That silence, however, became a double-edged sword. Nollywood ran with his story, sometimes flattening it, sometimes honoring it, but always invoking his name. Without Achebe’s direct guidance, filmmakers turned him into both a source of authority and a shield against criticism.

Achebe’s Death and the Unfinished Conversation

When Chinua Achebe died on March 21, 2013, at the age of 82 in Boston, the world mourned not only the passing of a literary giant but the silencing of a conscience. Tributes flowed from presidents, poets, and professors across the globe. Nigeria declared him the “Eagle on the Iroko,” a voice that had carried Africa into the global literary arena. But amid the flood of tributes was also a haunting question: what would become of Achebe’s vision on screen, now that he could no longer speak for it himself?

His death marked a turning point for Nollywood. While Achebe lived, his towering presence cast a shadow of caution. Filmmakers hesitated to take bold liberties with Things Fall Apart, fearing the possibility — however remote — of his disapproval. His silence on Nollywood’s adaptation was protective, but it was also restrictive. After his passing, Nollywood suddenly found itself unmoored. The author could no longer guide, correct, or intervene. What remained were his words, his essays, and his carefully chosen silences.

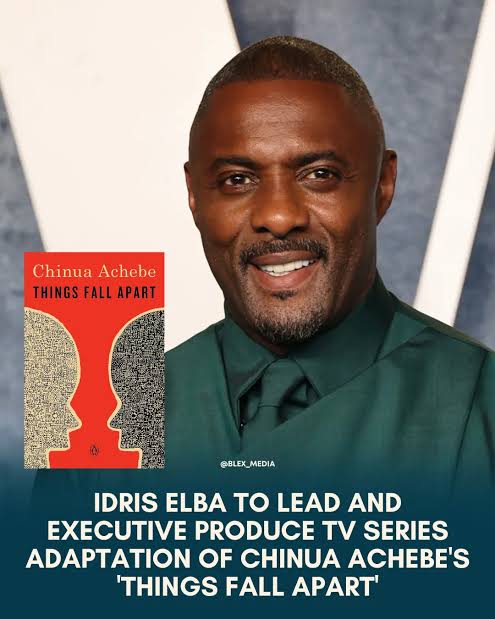

Idris Elba and the Global Stakes

Fast-forward to 2024, and Things Fall Apart remains one of the most globally taught African novels. Hollywood has circled it for years, with various rumors of adaptations involving international actors. The name Idris Elba, in particular, has surfaced repeatedly in speculative discussions. Elba, with his global recognition and African heritage, represents the kind of star who could bridge worlds — African authenticity and global reach.

What would Achebe have said about Idris Elba as Okonkwo? We cannot know. But we can guess. Achebe valued cultural integrity above spectacle. He would have demanded not just a star, but a cast and crew deeply rooted in the Igbo context of the novel. He would have insisted that Elba, or any actor, learn the cadences, the gestures, the silences of Achebe’s people. For Achebe, global visibility without local authenticity was meaningless.

And yet, his silence also leaves open the possibility that future adaptations could transcend Nollywood’s limitations. With technology, budgets, and global interest aligning, there remains a chance to finally give Things Fall Apart the cinematic sweep it deserves — without losing the cultural soil from which it sprang.

Conclusion: The River Still Flows

In the end, what Achebe said and didn’t say about Nollywood’s Things Fall Apart is as important as the adaptation itself. He said that Africans must reclaim their narratives. He didn’t say how those narratives must look on screen. He said that misrepresentation was dangerous. He didn’t say that imperfection was unforgivable.

Pete Edochie’s Okonkwo remains one of Nollywood’s most enduring achievements — a performance that still haunts classrooms and conversations. But Nollywood’s adaptation also revealed the industry’s struggle with depth, fidelity, and nuance. Achebe’s silences gave Nollywood space, but also left it with questions it has yet to answer.

The river of Achebe’s vision still flows, and Nollywood remains one of its many channels. Whether future adaptations — perhaps with Idris Elba at the helm, perhaps not — can deepen that channel rather than shallow it will determine how Achebe’s voice is carried forward. What is certain is that Things Fall Apart has never stopped speaking. And neither has Nollywood.