Lagos is not kind to dreamers. The city carries its own pulse—a soundscape of danfo horns, market women’s bargaining cries, and the restless push of bodies against the tide of survival. In its underbelly, ambition is both a blessing and a curse, measured not by the rhythm of applause but by the rhythm of resilience.

- The Lagos Soundscape: A City That Tests Every Voice

- Family Roots and Cultural Shadows: The Inheritance of Rebellion

- The Struggles of Early Lagos Gigs: Sweat, Noise, and Rejection

- Afro-Fusion as Rebellion: Defying the Industry’s Comfort Zone

- Clashes with Gatekeepers: The Politics of Fame in Lagos

- The Streets and the Blues: Lagos as Wound and Muse

- Before the World Knew Him: The Unseen Years of Near Collapse

- The Diaspora Pull: Leaving Lagos, Carrying Lagos

- Shadows of Controversy: The Blues of Reputation

- The Turning Point: “African Giant” and Lagos’s Reluctant Embrace

- Global Recognition, Lagos Shadows

- The Activist Thread: Lagos as Battlefield

- Monsters of the City: Blues as Protest

- Identity and Defiance: The African Giant Philosophy

- Lagos as Mirror: The Global Stage and Its Shadows

- Lagos as Womb and Wound: A Conclusion in Blues

For many, Lagos is a place where voices vanish before they are ever heard, drowned out by the sheer weight of noise, politics, and poverty. Yet, in that chaos, some rise—not instantly, but after years of being tested, broken, reshaped.

Long before the Grammys called his name, Burna Boy walked the narrow corridors of this city’s struggle. His Lagos blues were not composed in luxury studios or within the global gaze of flashing cameras.

They were written in sweat-drenched concerts with half-broken microphones, in nights when electricity failed and generators coughed smoke into the humid air, in the battles with gatekeepers who doubted that Afro-fusion had a place on the world stage.

The story of Burna Boy is not just about the meteoric rise of a Grammy-winning artist. It is about Lagos—the city that hardened him, rejected him, embraced him, and in the end, gave him a stage big enough to carry his defiance to the world. To understand Burna Boy, one must first understand the bruises behind the brilliance, the silence before the sound, the Lagos that gave him the blues before it gave him the spotlight.

The Lagos Soundscape: A City That Tests Every Voice

To write about Burna Boy without writing about Lagos is to tell half a story. The city itself is a character in his journey—a place where the music never truly stops, but neither does the struggle. The music of the city does not come from instruments alone. It rises from the clattering of danfo buses, the chant of street preachers, the unrelenting beat of generators humming through the night.

For young musicians, Lagos can be a proving ground or a graveyard. Success depends not only on talent but on survival instincts, connections, and the will to withstand endless rejection. Before Afro-fusion was celebrated on international stages, it was dismissed by many Nigerian gatekeepers as “too experimental,” “too foreign,” or “too risky for the mainstream.”

Burna Boy, born Damini Ebunoluwa Ogulu in Port Harcourt, entered Lagos at a time when Nigerian music was undergoing a revolution. The mid-to-late 2000s had seen the explosion of Afrobeats acts like D’banj, 2Baba (formerly 2face Idibia), P-Square, and later Wizkid and Davido. These artists were crafting a sound that leaned heavily on pop and dance, a sound designed to move bodies in clubs and dominate radio airplay. For the music industry, commercial success meant sticking to formulas that sold. Afro-fusion—a genre Burna insisted on creating—did not fit those formulas.

What Lagos demanded of him was resilience. The city did not welcome his sound with open arms. Instead, it tested his ability to insist on it, to fight for it, to carry it even when audiences walked out of early shows or when labels refused to back his experiments. Lagos gave him not just exposure but obstacles—and it is in those obstacles that Burna Boy’s Lagos blues were composed.

Family Roots and Cultural Shadows: The Inheritance of Rebellion

Behind Burna Boy’s music lies a heritage steeped in both privilege and pressure. His grandfather, Benson Idonije, was not just another elder in the family—he was the first manager of Fela Anikulapo Kuti, the Afrobeat pioneer whose music was as much a political statement as it was a cultural revolution.

For many Nigerians, Fela represented fearless defiance, the audacity to call out military dictatorships, and the insistence that music must serve truth, no matter how costly.

This legacy weighed heavily on Burna Boy. On one hand, it gave him an invisible inheritance: access to stories, rhythms, and philosophies that few of his peers could claim. On the other hand, it placed him in a shadow that could easily have consumed him. How do you walk your own path when the ghost of Fela looms over your shoulder? How do you make music that is both authentic and distinct, without being dismissed as a mere echo of your grandfather’s legend?

Burna Boy’s mother, Bose Ogulu, also played a crucial role. An academic and later his manager, she gave structure to his chaotic brilliance. She became both anchor and enabler, ensuring that his rebellious energy was not wasted in self-destruction. Yet, even with this strong family support, Burna still had to wrestle with Lagos itself—a city that does not care about your lineage.

In Lagos, you are not judged by who your grandfather managed or which intellectual roots you claim. You are judged by your ability to move the crowd, to command attention in clubs from Surulere to Victoria Island, to prove that your sound can thrive in a market saturated with pop formulas. Burna’s blues began here, in the space between his inheritance and the harsh reality of Lagos survival.

The Struggles of Early Lagos Gigs: Sweat, Noise, and Rejection

Every superstar has untold nights of failure, and for Burna Boy, many of those nights played out in Lagos. In the early 2010s, when he began performing in the city’s circuit of small clubs, university shows, and underground venues, audiences did not always understand him. His sound was a blend of reggae, dancehall, highlife, hip-hop, and Afrobeat—what he would later call Afro-fusion. But in Lagos, where radio DJs wanted three-minute club bangers and promoters wanted instantly recognizable hooks, Burna’s music seemed “too strange” or “too heavy.”

There were times he would mount a stage only to see half the audience distracted, waiting for the “real stars” of the night to appear. Promoters underpaid him or canceled shows entirely. Industry insiders advised him to abandon the fusion and “stick to Afrobeats” if he wanted to survive. But Burna, with his characteristic stubbornness, refused to dilute his sound.

This defiance came at a cost. He was often broke, moving between borrowed apartments and studio couches. Lagos’s infamous traffic made it worse—stranded after gigs, carrying frustrations home in the dead of night. At times, his friends wondered if his refusal to bend would bury his career before it even began.

But those nights of rejection would later feed into his artistry. Songs like “Another Story” and “Dangote” carry the weight of Lagos’s contradictions—its poverty alongside its opulence, its dreams alongside its disappointments. The blues of Lagos were not abstract for Burna Boy. They were lived, embodied, and endured.

Afro-Fusion as Rebellion: Defying the Industry’s Comfort Zone

In the history of Nigerian music, Burna Boy’s insistence on Afro-fusion marked an act of rebellion. While Wizkid leaned into pop-driven Afrobeats and Davido into hit-making anthems, Burna chose to experiment. Afro-fusion was messy, unpredictable, and harder to package for radio playlists. But for Burna, it was the only honest reflection of who he was—a child of Port Harcourt exposed to reggae, an heir to Afrobeat consciousness, a youth immersed in Lagos’s hip-hop culture.

He once described his music as a space where “all the sounds I grew up with meet.” In many ways, Afro-fusion was Lagos itself—noisy, contradictory, layered with influences, yet alive with energy. But to Nigerian labels in the early 2010s, Afro-fusion was a commercial risk.

This tension came to a head with the release of “Like to Party” in 2012, the single that first announced Burna to the wider Nigerian audience. The song was more accessible than his earlier experimental work, yet it still carried his unique fusion. Lagos embraced it cautiously, playing it in clubs, testing its pull on dancefloors. It worked, and slowly, doors began to open. But even then, Burna’s relationship with the Lagos establishment remained uneasy. He was never the darling of industry gatekeepers. He was always the outsider who forced his way in.

Clashes with Gatekeepers: The Politics of Fame in Lagos

To survive in Lagos’s music industry, many artists align themselves with powerful cliques—labels, promoters, or political patrons. Burna Boy refused such alignment, and that refusal made his journey harder. His outspokenness often came across as arrogance. He criticized radio DJs, mocked other artists for being “industry puppets,” and insisted that his sound would prevail without compromise.

This defiance created enemies. Burna often found himself blacklisted from shows, excluded from award nominations, or dismissed by critics who labeled him “difficult.” He was not the smiling pop star Lagos was used to. He was confrontational, outspoken, and unwilling to play nice.

Yet, history has shown that Lagos, despite its resistance, cannot ignore authenticity forever. Over time, the very qualities that alienated Burna became the source of his appeal. Lagos eventually recognized in him something it could not deny—a rawness that reflected its own contradictions, a fearlessness that echoed its own survival spirit.

The Streets and the Blues: Lagos as Wound and Muse

More than the clubs of Victoria Island or the studios of Lekki, it was the streets of Lagos that gave Burna Boy his narrative depth. Walking through Ojuelegba, Mushin, or the mainland’s endless sprawl, he saw the realities hidden behind the city’s glittering skyline: children hawking goods in traffic, families crammed into single rooms, and young men hustling with dreams bigger than their resources.

These images found their way into his lyrics, not as abstract social commentary but as lived reality. “Dangote” captured the endless hustle, “Collateral Damage” spoke to political betrayal, and “Monsters You Made” echoed the frustrations of a generation.

The Lagos blues, for Burna, were not simply personal struggles. They were collective struggles. His artistry became a mirror of a city that celebrates even as it suffers, a city where music is not escapism but survival.

Before the World Knew Him: The Unseen Years of Near Collapse

By the time “Like to Party” secured him a foothold in 2012, Burna Boy had already fought battles that left scars deeper than the applause could heal. He was 21, restless, and finally receiving the kind of radio play he had once begged for. Yet, as often happens in Lagos, success did not arrive in peace—it came tangled in fresh complications.

The Nigerian music industry is unforgiving to young stars. Many are swallowed by bad contracts, manipulative promoters, or the weight of sudden fame. Burna Boy was no exception. His relationship with Aristokrat Records, the label that helped launch him, grew strained. Disputes over money, direction, and control mirrored the very struggles he had resisted. By 2014, after his debut album “L.I.F.E” received critical acclaim but left him frustrated, he parted ways with the label.

This exit was not smooth. It triggered rumors that he was “finished,” whispers that his arrogance had finally burned too many bridges. For a time, Burna seemed adrift—visible but unstable, talented but chaotic. Lagos thrives on gossip, and it was during this period that he earned the reputation of being “too difficult” to work with, a tag that would follow him for years.

But in hindsight, these years of turbulence were the crucible. They forced him to reimagine what independence meant, to reassert his identity outside the shadow of labels and industry politics. It was a gamble that could have left him forgotten. Instead, it became the foundation of the next phase of his Lagos blues.

The Diaspora Pull: Leaving Lagos, Carrying Lagos

When Lagos closed doors, Burna Boy looked outward. The Nigerian diaspora has long been both audience and lifeline for musicians, offering stages beyond the crowded ecosystem of the mainland. London, in particular, has been a second home for Afrobeat and its descendants, dating back to Fela’s own days of performance and exile.

Burna Boy tapped into this legacy. His tours in the UK exposed him to audiences who were less constrained by the formulas of Nigerian radio. In the diaspora, Afro-fusion sounded fresh rather than risky. It resonated with young Africans abroad who were negotiating their hybrid identities, caught between the cultural memory of their parents and the global influences around them.

Yet, even in London, Burna’s Lagos blues followed him. He was not yet the global star who would sell out the O2 Arena. In those early years, he was still hustling for relevance, often performing to modest crowds, still haunted by industry skepticism back home. Diaspora stages gave him room to breathe, but Lagos remained the ground where his credibility would ultimately be tested.

His 2015 album “On a Spaceship” reflected this tension—expansive in ambition, but uneven in reception. Nigerian critics dismissed it as unfocused. For Burna, however, it was less about instant success and more about refusing to retreat into conformity. Every track was another refusal to compromise, another statement that Afro-fusion was here to stay.

Shadows of Controversy: The Blues of Reputation

For all his talent, Burna Boy’s Lagos story cannot be told without acknowledging his controversies. In 2017, legal troubles and public spats nearly drowned his career. An alleged involvement in an assault case forced him to withdraw temporarily from the scene. Nigerian tabloids feasted on the scandal, painting him as reckless, arrogant, and self-destructive.

These years could easily have marked the end. Lagos has little patience for stars who appear to squander their chances. Many musicians before him had disappeared into obscurity after one scandal too many. But Burna Boy’s story unfolded differently. Instead of fading, he seemed to absorb the chaos, folding it back into his artistry.

By 2018, he roared back with “Outside”, an album that finally aligned his sound with global attention. Songs like “Ye”—ironically boosted by Kanye West’s album of the same title—became anthems. Lagos, which had once doubted him, began to sing along. Suddenly, Burna was no longer the outsider knocking on the industry’s doors. He was the force breaking them down.

But the irony remained: the blues that shaped him—the rejection, the controversies, the endless struggle to prove himself—were also the very elements that made his rise irresistible. Without the pain, there would have been no power. Without Lagos’s wounds, there would have been no world-stage warrior.

The Turning Point: “African Giant” and Lagos’s Reluctant Embrace

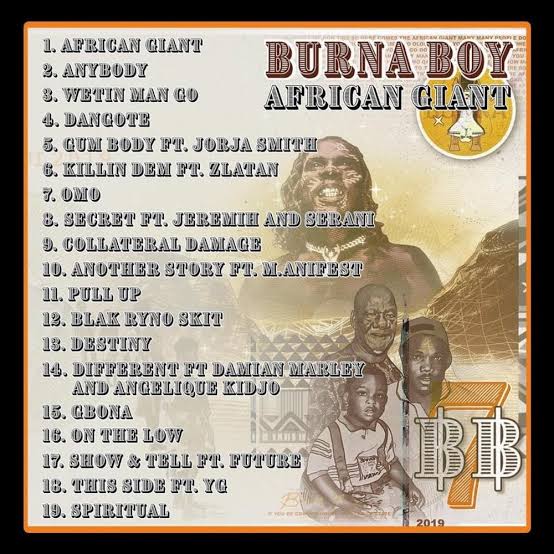

By 2019, Burna Boy had reached a point Lagos could no longer ignore. His album “African Giant” was not just a musical project—it was a manifesto. Here was a Nigerian artist insisting on continental pride, unafraid to confront global systems, yet still deeply rooted in Lagos’s survival culture.

The album was both local and global. Tracks like “Gbona” and “On the Low” dominated Lagos airwaves, while “Anybody” and “Dangote” carried the restless blues of Nigerian hustle into international playlists. Lagos, which had once treated Afro-fusion with suspicion, now embraced it with open arms.

But perhaps the most symbolic moment was Burna Boy’s headline performance at Coachella 2019. Annoyed that his name appeared in small print on the festival’s flyer, he declared himself the “African Giant” and demanded recognition. Lagos understood this defiance—it was the same defiance the city itself lived by every day. In his arrogance, Lagos saw its reflection.

That same year, “African Giant” earned him his first Grammy nomination. For the boy once dismissed as too strange for Lagos radio, this was vindication. Yet, even then, he would not win. The Grammy would slip from his hands, a reminder that struggle was not over. But Lagos had already given him its reluctant embrace, and the world was now watching.

Global Recognition, Lagos Shadows

When Burna Boy finally won the Grammy in 2021 for “Twice as Tall”, it was celebrated worldwide as the triumph of Afro-fusion. Newspapers hailed him as a cultural ambassador, the face of a new African soundscape. But to understand that moment is to remember that behind the glittering trophy lay Lagos’s bruises.

Every note he sang carried the weight of early rejections, unpaid gigs, broken promises, and personal controversies. The Lagos blues were not erased by the Grammy—they were immortalized by it. For every global fan who danced to his hits, there were countless Lagos nights where he wondered if his sound would ever matter.

Even now, Burna Boy remains a paradox in Lagos. He is both celebrated and critiqued, embraced and questioned. His relationship with the city is as restless as the city itself. He does not belong to Lagos alone, but he cannot be understood without it.

The Activist Thread: Lagos as Battlefield

For all its rhythms and resilience, Lagos is also a city of protest. Its streets have witnessed uprisings against military regimes, marches for democracy, and more recently, the collective rage of a generation demanding change during the EndSARS protests of October 2020. Burna Boy’s Lagos blues reached their sharpest edge here—not just in personal struggle, but in political confrontation.

Though often accused of being aloof in Nigeria’s activist circles, Burna has repeatedly used his music as a weapon. In “Monsters You Made”, released just months before EndSARS erupted, he warned of the violence bred by systemic neglect and corruption. The lyrics were not abstract—they echoed the lived frustrations of Lagos youth, harassed daily by police units like SARS, exploited by politicians, and left to hustle without safety nets.

When the protests reached their tragic climax at the Lekki Toll Gate, with live bullets cutting into unarmed demonstrators, Burna Boy responded not with silence but with mourning. He financed billboards demanding justice, released tributes, and lent his platform to amplify the pain. Lagos had given him his blues, and in this moment, he gave voice to Lagos’s cries.

The city’s young people heard him, not just as an entertainer, but as one of their own—someone who had once walked their paths, carried their frustrations, and now stood in solidarity. In many ways, EndSARS crystallized what Burna’s music had long suggested: Lagos is not only a stage for dreams but a battlefield where survival itself is political.

Monsters of the City: Blues as Protest

The Lagos blues Burna Boy carries are inseparable from Nigeria’s national history. Colonial exploitation, military dictatorship, economic inequality—these are not distant textbooks but living realities that shape the city daily. Burna’s genius lies in translating these realities into soundtracks that travel beyond borders without losing their local sting.

“Collateral Damage” calls out the complacency of citizens numbed by corruption. “Another Story” lays bare the colonial theft that set Nigeria on its current path. These are not safe songs designed for club play alone; they are protest chants wrapped in Afro-fusion, crafted to carry Lagos’s frustrations into global consciousness.

In this, Burna mirrors his grandfather’s legacy with Fela. But while Fela confronted dictators head-on with horns and smoke-filled shrines, Burna employs the language of the global music industry—streaming platforms, international festivals, collaborations with Western stars. His rebellion is not just in the lyrics but in his ability to make Lagos’s blues resonate in Los Angeles, London, and Lisbon.

Every protest line is layered with personal memory: nights without electricity, friends lost to police brutality, Lagos traffic jams that waste lives as surely as poverty. Burna does not sing of monsters in the abstract. He sings of monsters he has seen, of monsters Lagos continues to birth in its endless cycle of hustle and despair.

Identity and Defiance: The African Giant Philosophy

By declaring himself the African Giant, Burna Boy claimed more than a title. He defined a philosophy—one rooted in Lagos’s unrelenting demand for survival and dignity. Lagos taught him that to be small is to be ignored, that the city devours those who do not roar.

In interviews, Burna has often insisted that he does not make Afrobeats but Afro-fusion, resisting the easy label applied by Western markets. This insistence is more than semantics; it is an act of identity. Afrobeats has become shorthand for African pop globally, but Burna insists his Lagos blues are too layered, too rebellious, too messy to fit neatly into one genre.

This defiance reflects the Lagos psyche itself—a refusal to be boxed in, a demand to be recognized on one’s own terms. To call himself African Giant was to echo Lagos’s own giant spirit, a city that refuses invisibility despite poverty, chaos, and dysfunction.

And yet, in this giant claim lies vulnerability. Burna Boy has repeatedly admitted to struggles with loneliness, with the burden of expectations, with the scars left by rejection. The African Giant is both armor and wound. His Lagos blues gave him the need for armor, but they also ensured the wound never fully heals.

Lagos as Mirror: The Global Stage and Its Shadows

When Burna Boy clinched the Grammy award in 2021 for “Twice as Tall”, it was more than personal triumph. It was Lagos standing beside him, Lagos demanding recognition through him. Yet, the city’s shadow remained.

For while Burna had reached global stardom, Lagos itself still struggled with the very issues his music protested—police brutality, poverty, corruption, failing infrastructure. His Grammy did not erase these realities; it only amplified the irony. How can a city that produces a global star remain so brutal to its ordinary citizens? How can Lagos dance to Burna Boy in clubs while living the very blues his lyrics describe?

This paradox is not unique to Lagos, but Lagos embodies it intensely. It is a city that celebrates its stars even as it neglects its masses. Burna Boy’s triumph became both a moment of pride and a mirror of contradiction. The African Giant was proof of Lagos’s creative power, but also of its failures.

Lagos as Womb and Wound: A Conclusion in Blues

The story of Burna Boy is not a neat arc from struggle to triumph. It is a cycle of wounds and healings, a dance between rejection and recognition, a blues that never fully resolves. Lagos was the womb that birthed him, shaping his rhythm, giving him stories, forging his defiance. But Lagos was also the wound that scarred him—through rejection, controversy, and endless battles for survival.

Without Lagos, there would be no Burna Boy. But without Burna Boy, Lagos would lack one of its fiercest mirrors. His music does not flatter the city; it exposes it. His sound does not escape its chaos; it translates it. His blues are Lagos’s blues, carried now across continents.

To listen to Burna Boy is to hear Lagos speaking in multiple tongues: the defiance of Afrobeat, the hunger of the streets, the mourning of lost dreams, the celebration of survival against all odds. His Grammys may shine in glass cases abroad, but the fingerprints on them belong to Lagos—the city that bruised him before it crowned him.

And so the story circles back to where it began: a city whose noise threatens to drown voices, but where, sometimes, a voice refuses to be drowned. Burna Boy’s Lagos blues remind us that greatness is not born in comfort. It is born in chaos, in defiance, in wounds that sing until the world finally listens.