Fame in Nigeria is a fragile armor. For decades, Pete Edochie and Nkem Owoh lived at the center of a world where illusion and reality intersect—where kings could rule without fear on screen, and jesters could turn hardship into laughter. But in real life, that armor is pierced.

Kidnappers did not chase wealth alone; they hunted recognition, visibility, the faces etched into a nation’s memory. When Pete was seized, the patriarch of Nollywood became a mirror for every citizen’s vulnerability. When Nkem followed, the jester’s absence reminded a country that laughter can vanish in an instant.

Their abductions were not random acts—they were deliberate collisions of power, fame, and fear. They transformed ordinary roads and towns into stages of tension, where survival was the only script that mattered.

This story traces the raw human dimensions behind headlines, beyond celebrity, into the intersections of terror, resilience, and a nation’s gaze fixed on its icons as they navigated danger not for art, but for life itself.

The Fragile Glamour of Nollywood

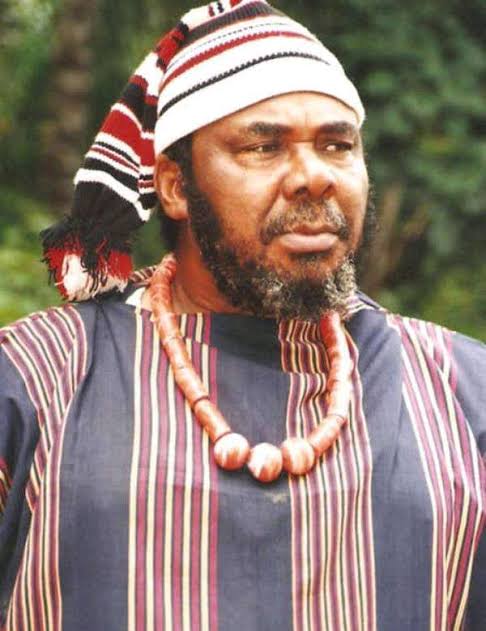

I) The Father of Nollywood Gravitas

To speak of Pete Edochie is to summon the image of Nollywood’s patriarch. His baritone, commanding yet measured, has long been the soundtrack to cinematic authority. Born in Enugu in 1947, Edochie grew into Nigeria’s collective consciousness through stage and screen, his breakthrough coming with the television adaptation of Things Fall Apart, where he embodied Chinua Achebe’s Okonkwo with such ferocity that his name became shorthand for African literary gravitas on screen.

For younger generations who never touched Achebe’s novel, it was Pete’s Okonkwo who defined manhood, power, and tradition. Over time, his roles crystallized into a kind of cultural shorthand: the king who held his court together, the father who would rather bend steel than see his household broken, the priest whose wisdom cut sharper than a blade. When Nigerians invoked “Lion of Nollywood,” they often meant him.

Yet, beyond the screen, Pete Edochie lived not as a demigod but as a man moving through a country reshaped by insecurity. He was both a towering icon and a citizen who drove the same roads riddled with armed bandits, a revered figure who knew the weight of ordinary fears.

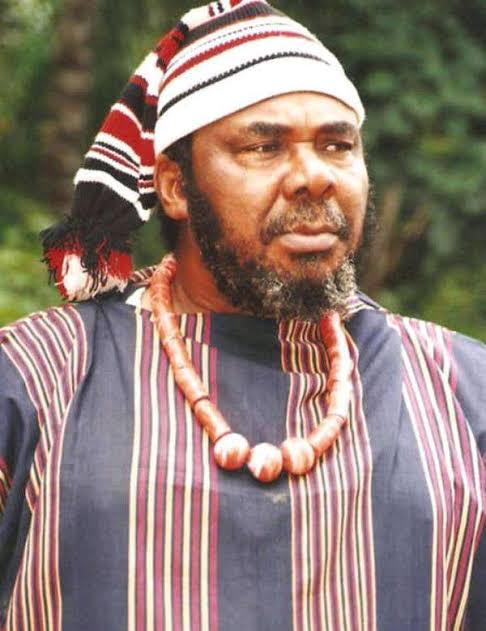

II) The Jester With Hidden Depths

If Pete was Nollywood’s patriarch, Nkem Owoh was its trickster. Where Edochie carried himself with solemnity, Owoh thrived on satire. Born in 1958, Owoh carved his space as Nigeria’s laughter-maker, though his comedy was rarely hollow. His breakout role in Osuofia in London (2003) turned him into an international name—the naïve villager stumbling through the absurdities of British society, exposing colonial hangovers with humor sharper than any political speech.

But Owoh was more than the clown of Nollywood’s village square. His comedic timing doubled as social critique. With a squint, a pause, or a stammer, he revealed hypocrisies in politics, corruption in families, and the human cost of greed. He embodied resilience through laughter, reminding Nigerians that comedy was not escape but survival.

In him, the nation saw its ability to endure—the trickster navigating impossible systems, laughing not because life was easy, but because laughter was sometimes the only weapon left.

III) Bound by Fragility

Together, Pete Edochie and Nkem Owoh represented the two ends of Nollywood’s emotional spectrum: the patriarch and the jester, gravity and satire. Yet, they shared one truth—both were men deeply woven into the fabric of Nigerian life, their images on posters and their voices echoing in living rooms across the continent.

That reach made them beloved. But it also made them visible targets. To kidnappers seeking quick ransom or symbolic victories, abducting such men meant piercing not just two families but a nation’s psyche. If Nollywood’s lion could be dragged into the shadows, if its eternal jester could be silenced, then no Nigerian could feel safe.

And so, the glamour of Nollywood—the awards, the global premieres, the acclaim—revealed its fragility. Behind the glitz, actors still commuted on risky highways, lived in towns with failing security, and navigated a country where fame was no shield against the economy of abduction.

Nigeria’s Kidnap Economy

To fully grasp how Nollywood’s patriarchs fell into the hands of abductors, one must step back into the wider crisis consuming Nigeria in the 2000s. Kidnapping in Nigeria did not spring up overnight—it grew, mutated, and entrenched itself into the country’s criminal economy, feeding off structural cracks that ran deep.

I) From Militancy to Marketplace

The Niger Delta of the early 2000s was a region on edge. Oil pipelines crisscrossed impoverished villages, pumping billions of dollars into state coffers while locals languished in underdevelopment. Out of this contradiction rose militant groups who, in their earliest years, justified kidnappings as weapons of protest. Oil workers—many expatriates—were snatched to force companies into negotiations or governments into concessions.

But soon, what began as political agitation metastasized into commerce. Militancy blurred into banditry; ransom became business. Kidnapping spilled from the creeks into highways, into towns, into cities. When the state’s inability to curb the trend became obvious, criminals outside the oil belt replicated the model. Anyone with a traceable fortune, anyone with visibility, became potential prey.

II) Nollywood in the Crosshairs

By the mid-2000s, Nollywood had risen into a cultural powerhouse. Nigerian films were watched in Ghana, Kenya, South Africa, and across diasporas from London to New York. Yet, back home, actors remained ordinary citizens, often without the protective infrastructure that fame in Hollywood guaranteed.

Kidnappers recognized a dual advantage: Nollywood stars were publicly recognizable, their families accessible, and their fan base wide enough that news of their capture would spread like wildfire. This visibility created pressure—on families, on industry stakeholders, on fans demanding safe return. Visibility translated into leverage, and leverage translated into ransom.

III) Fear on Set and on the Road

The fear reshaped Nollywood’s ecosystem. Film producers worried about location shoots in remote areas. Actors became cautious about traveling by road—yet road travel was often unavoidable in an industry still struggling with financial margins. Security escorts were luxuries, not standard. The very roads that carried actors to the towns where their stories were filmed also carried the risk of abduction.

It was within this climate—where kidnapping had become an “industry” and Nollywood its high-profile market—that Pete Edochie fell into the trap in 2009.

Pete Edochie’s Ordeal

I) The Night the Lion Was Caged

September 2009. The commercial city of Onitsha, Anambra State, hummed as usual—a place where traffic never really slept, where markets buzzed even at twilight. Pete Edochie, at 62, remained as commanding off-screen as on, yet that day he was simply another traveler navigating Nigeria’s vulnerable roads.

The ambush was sudden. A convoy of armed men blocked the path, their weapons dictating the next moments. Nollywood’s patriarch—the man who had embodied kings—was wrested from control. The news, once it broke, spread like fire through dry grass: Pete Edochie had been kidnapped.

For many Nigerians, it was unthinkable. How could the man whose proverbs filled countless films, whose presence commanded silence in village squares, now be a captive? Newspapers carried the story with urgency. Radio hosts spoke in hushed tones, and markets buzzed with whispers. The abduction wasn’t just crime—it was cultural desecration.

II) The Weight of Symbolism

Pete’s ordeal was not only personal; it was symbolic. To abduct him was to demonstrate that no hierarchy was sacred. If the lion of Nollywood could be dragged from the open, then kings, chiefs, businessmen, even ordinary traders, were equally vulnerable. It was a message scrawled not in ink but in fear.

His captors demanded ransom, though exact figures remained muddied in public reports. Some accounts hinted at millions, others at more modest sums. What mattered was not the arithmetic but the psychology: they held a man whose face was stamped in Nigeria’s collective imagination. Every passing day stretched the tension.

III) The Release

After days in captivity, Pete Edochie was released. The details of negotiations were never fully revealed—Nollywood, like many Nigerian families struck by kidnapping, preserved silence around ransoms paid. But his return was met with relief that rolled like thunder across the nation.

Crowds welcomed him with prayers. Fans saw in his survival not just fortune but resilience. He emerged, not broken, but more layered—a man whose screen gravitas had been tested in real life. Yet, the scars were not invisible. For Pete, the abduction etched itself as a reminder of mortality, of fragility, of the thin veil separating fame from vulnerability in Nigeria.

Nkem Owoh’s Abduction

I) The Road to Enugu

It was late 2009, barely months after Pete Edochie’s release, when news broke that shook Nollywood once again. This time, it was Nkem Owoh—the man whose laughter had lifted millions, whose roles balanced comedy and critique—snatched from the open.

Owoh had been traveling near Enugu, his home state and artistic base, when armed men intercepted him. Unlike Pete’s abduction, which unfolded in Onitsha’s sprawling commercial chaos, Owoh’s capture occurred closer to the heartland of his own identity. For his fans, it felt like the disruption of a sanctuary, as though even the soil that birthed his wit could not protect him.

II) A Nation in Shock

The news sent a ripple of disbelief across Nigeria. Nkem Owoh was not just another actor—he was Osuofia, the bumbling villager turned global sensation in Osuofia in London. He was the people’s comedian, a man who made jokes out of hardship and gave ordinary Nigerians a mirror of resilience. His kidnap felt personal to every fan.

Newspapers carried stark headlines: “Nollywood Star Owoh Abducted.” Radio stations replayed the report every hour. In Enugu, panic swirled around markets and motor parks; women selling peppers whispered of the comedian dragged away by faceless men.

The kidnappers demanded ransom. Reports varied wildly—some said ₦15 million, others suggested lower sums—but the figure mattered less than the symbolism: Nigeria’s beloved jester was now bargaining for his life in silence, his laughter swallowed by fear.

III) The Family’s Ordeal

Behind the headlines was a family in torment. His wife and children endured sleepless nights, their privacy invaded by speculating journalists and neighbors pressing for updates. Unlike politicians or oil executives, Nollywood actors did not command vast personal wealth, yet kidnappers operated on the perception of affluence. Every day in captivity carried its own dread: would negotiation succeed? Would violence erupt? Would Nkem Owoh, the man who made Nigeria laugh, become another tragic statistic?

IV) The Release

After several days, Owoh was released. As with Pete Edochie’s case, the details of ransom payments remained shrouded in silence. But his return was greeted with relief bordering on euphoria. Crowds gathered at his home, singing, praying, and thanking God. Fans celebrated not only his safety but the restoration of laughter itself.

Yet, beneath the joy lingered a haunting truth: the jester had walked into the shadowland and returned. His laughter carried new weight. On screen, every grin, every pause, every mischievous squint bore the invisible mark of someone who had stared at fear too closely.

When Icons Become Targets

I)The Collapse of Illusion

The kidnappings of Pete Edochie and Nkem Owoh shattered a collective illusion. Nigerians had long treated their stars with reverence, as if fame itself conferred immunity. But in a country where abductions stretched from oil workers to schoolchildren, it was only a matter of time before celebrity joined the list.

Kidnappers understood the psychology of recognition. Abducting a businessman drew private negotiations, but abducting a Nollywood icon unleashed national outcry. The victims’ faces were instantly recognizable, their absence deeply felt. Every newspaper headline, every whispered conversation, every church prayer turned their captivity into public spectacle.

II) Symbolic Violence

For ordinary Nigerians, the abductions carried symbolic violence. Pete Edochie was not merely an actor; he embodied fatherhood, tradition, and authority. To see him in chains—even if unseen, only imagined—was to witness the symbolic dethronement of a king.

Nkem Owoh, in contrast, represented the resilience of laughter. His abduction struck at the heart of Nigeria’s coping mechanism: humor amid hardship. When Osuofia was silenced, Nigerians felt the fragility of their own defense against despair.

III) The Ripple Effect in Nollywood

Producers and directors grew wary. Rumors swirled of actors canceling shoots in rural areas, of film crews hiring local vigilantes for protection. Budgets swelled to accommodate security costs. Some producers quietly admitted relocating storylines from isolated villages to safer city locations, sacrificing authenticity for survival.

Younger actors watched with unease. If legends like Pete and Nkem could be dragged into the shadows, what hope did newcomers have? The glamour of stardom now shimmered with the reflection of danger.

IV) The National Psyche

For Nigeria, a country already fatigued by news of daily abductions, the kidnapping of icons was a wake-up call. It reminded citizens that insecurity respected no hierarchy. The rich, the poor, the famous, the forgotten—all were prey in a land where kidnapping had become lucrative business.

Pete and Nkem’s ordeals became cultural reference points. When later kidnappings struck clerics, students, or politicians, Nigerians often compared them to those earlier incidents, recalling how even Nollywood’s brightest stars had once been swallowed by fear.

Survivors, Not Victims

I) Reclaiming the Screen

In the months following their abductions, both Pete Edochie and Nkem Owoh faced a choice—withdraw into guarded silence or return to the screen that had made them icons. Both chose the latter. Their resilience became, in itself, a form of testimony.

Pete Edochie resumed his roles with an even deeper gravitas. In films where he played fathers under siege, or monarchs betrayed by their own chiefs, audiences could not help but read his personal history into the performances. His eyes carried an extra weight, his pauses spoke of realities beyond the script. When he thundered against injustice on screen, Nigerians knew he had lived its shadow in real life.

Nkem Owoh, for his part, doubled down on comedy. Yet, beneath the laughter, viewers sensed an undercurrent of survival. His jokes felt sharper, his satire more poignant. He reminded Nigerians that humor was not frivolity but resistance—a way of asserting life in the face of death. The jester who had once parodied hardship now embodied resilience itself.

II) Public Silence, Private Scars

Neither Pete nor Nkem spoke extensively about their ordeals. Like many kidnap victims in Nigeria, they maintained discretion around ransom details and negotiations. Silence was not only a matter of privacy—it was protection. To speak too openly risked emboldening future abductors, or exposing families to renewed danger.

But silence does not erase scars. Trauma manifests quietly: a hesitation on dark roads, a second glance at strangers, a heaviness in private conversations. Survivors often walk with invisible burdens—burdens that audiences might not see when the cameras roll, but which shape the rhythms of life long after release.

III) Redefining Stardom

In their survival, both men redefined what it meant to be a Nollywood star. Stardom was no longer simply about fame, glamour, or applause. It was about endurance. To be a Nigerian actor was to live with the knowledge that the spotlight could attract danger, that celebrity was not only a crown but a target.

Yet, by continuing their craft, Pete and Nkem transformed victimhood into resilience. They did not become symbols of tragedy but of perseverance. In this, they gave their fans more than entertainment—they offered a template for navigating Nigeria’s collective struggle with insecurity.

The Wider Epidemic

I) Nollywood’s Vulnerable Stars

The abductions of Pete Edochie and Nkem Owoh were not isolated incidents. Over the years, Nollywood has been repeatedly shaken by reports of actors, producers, and crew members falling victim to kidnappers.

Patience Ozokwor—popularly known as “Mama G”—was at one point rumored to have been kidnapped, though reports later clarified she had been harassed but not abducted. Still, the rumor itself reflected a growing public fear: that Nollywood’s most familiar faces were perpetually at risk.

Other actors, particularly those working in rural locations, were accosted by armed men demanding quick ransom. In some cases, entire film crews were held hostage until payments were made. The film industry became both a mirror and a participant in Nigeria’s insecurity drama.

II) Beyond Nollywood

But the epidemic spread far beyond the film industry. Politicians, businessmen, clergy, and ordinary citizens were abducted daily. Students on school buses were taken in groups. Traders on highways vanished into the forests. Families mortgaged land, sold property, and emptied savings to pay for releases.

The phenomenon cut across class lines. Wealthy elites were targeted for millions, while villagers were held for sums as small as ₦50,000. Kidnapping became democratized—a crime where every life, no matter the economic bracket, had a negotiable price.

III) The Numbers Behind the Fear

By the late 2000s and early 2010s, media reports estimated that Nigeria had one of the highest kidnap-for-ransom rates in the world. Human rights groups documented thousands of cases annually, though many went unreported for fear of reprisal. The crime had become an industry worth billions of naira, sustained by corruption, poverty, and weak policing.

Insecurity was no longer a background condition—it was the main stage on which Nigerian life unfolded. Pete and Nkem’s ordeals stood out because of their fame, but they were part of a broader story that touched nearly every family in the country.

IV) Cultural Reverberations

Nollywood, ever a mirror of society, wrestled with whether to dramatize these realities. A handful of films began exploring abduction themes, often sensationalized, sometimes oversimplified. But for many filmmakers, the rawness of the issue made it difficult to portray without reopening wounds. How do you turn into fiction what your colleagues have lived as fact?

Instead, kidnappings remained more a backdrop than a centerpiece. The silence of Nollywood on its own scars revealed the depth of the trauma: some stories were too close to home to dramatize.

V) A Nation Desensitized

As kidnappings multiplied, Nigerians grew both hyper-alert and paradoxically numb. Each new report sparked outrage, but outrage faded quickly into resignation. When even beloved actors could be taken, the message was clear: insecurity was no respecter of status.

In conversations, citizens often referred back to Pete and Nkem’s ordeals as cultural milestones. Their abductions were shorthand for the era when kidnapping shifted from rare shock to common fear. Their survival offered hope, but their captivity confirmed what everyone dreaded: no one was truly safe.

Art Imitating Life, or Life Outrunning Art?

I) Fiction vs. Reality

Nollywood has long thrived on the interplay of drama and morality, of crime and consequence. Yet, for all its stories of betrayal, greed, and peril, the real-life kidnappings of Pete Edochie and Nkem Owoh revealed a paradox: fiction could not fully capture the terror of reality.

In scripted thrillers, audiences are aware that danger is contained—credits roll, the villain is punished, the hero survives. But in Nigeria’s actual landscape of abductions, there are no guarantees. Real kidnappers do not pause for dramatic effect, do not script mercy. Survival depends on negotiation, luck, and patience. The stakes are absolute, and every misstep can be fatal.

II) The Ethical Dilemma

Filmmakers wrestle with an ethical dilemma: how to portray kidnappings without sensationalizing trauma? Early attempts often fell flat, reducing complex experiences to simple plot devices. Many survivors, including Nollywood stars themselves, discouraged dramatization. To turn lived fear into entertainment risked trivializing pain while potentially endangering families still living in high-risk areas.

The result: Nollywood largely avoided fully immersive portrayals of celebrity abductions. The real stories—Pete’s and Nkem’s—remained mostly behind closed doors, whispered in interviews or implied through performances. In this silence lay a profound statement: some scars are too raw for public consumption, and some truths are better honored in lived memory than on screen.

III) Audience Reflections

For viewers, this gap between reality and fiction created a subtle tension. When actors like Pete or Nkem portrayed danger, betrayal, or captivity on screen, audiences unconsciously overlaid their real-world experiences. Laughter was tinged with anxiety, reverence with unease. Art, in these cases, became a reflection not only of imagination but of the collective trauma etched into the nation’s consciousness.

Legacy and Lessons

I) Icons as Symbols of Resilience

Pete Edochie and Nkem Owoh emerged from their abductions as more than actors—they became living symbols of resilience. Their survival transcended the personal; it was national. They demonstrated that even in a society where fear stalks the highways, courage can endure.

Pete’s gravitas grew not just from his artistic talent but from the lived authority of one who had confronted real danger. Nkem’s humor deepened, enriched by the knowledge that laughter can persist even in the shadow of trauma. Together, they illustrated that resilience is not absence of fear, but mastery over it.

II) Lessons for Nigeria

Their stories offer lessons beyond entertainment. They highlight the vulnerabilities inherent in fame and wealth, underscore the need for stronger policing and security infrastructure, and humanize the statistics that dominate headlines. Kidnapping is often discussed in numbers—how many abducted, how much ransom—but Pete and Nkem remind the nation of the human cost: the sleepless nights, the psychological weight, the fragile hearts behind every reported case.

Moreover, their ordeals illuminate the intersection between celebrity and civic responsibility. When actors become victims, public empathy swells, and a conversation about insecurity enters homes that might otherwise remain insulated. Their experiences prompt reflection on how a nation safeguards its citizens, regardless of status.

III) The Cultural Imprint

Beyond policy and security, Pete and Nkem’s abductions reshaped cultural imagination. Nollywood’s narratives now carry the implicit gravity of lived terror; audiences understand that behind every character’s struggle lies a mirror of Nigeria’s real dangers. The lion still roars, the jester still laughs—but both do so with the awareness that life is precarious, that survival itself is heroic.

Closure: Surviving the Invisible Edge

The return of Pete Edochie and Nkem Owoh was not a simple relief; it was a recalibration of what it means to endure in a country where danger is woven into daily life. Authority, humor, fame—none of it protects against the calculated reach of abduction. Yet survival does not merely resist fear; it transforms it.

Pete carries a new gravitas, a weight unseen but unmistakable. Nkem’s laughter is sharper, layered, resilient, a testimony to the power of returning from the edge. They embody survival as an art form, teaching the nation that courage is as ordinary as it is extraordinary.

Their ordeals reframed Nollywood, turning the industry’s collective imagination toward vulnerability, risk, and the ethics of storytelling. Audiences now see more than actors—they see men who have traversed shadows and returned whole enough to continue shaping culture.

In the end, Pete and Nkem are symbols of continuity and human strength. Their stories are reminders that even when terror interrupts life, it cannot fully erase the essence of courage, resilience, and the will to return to light.