Long before the world crowned him as the lion of reggae, before his dreadlocks became a banner of resistance and his voice a hymn of liberation, Bob Marley was already chasing something that carried the same pulse as his music — a football rolling across a patch of dry Kingston earth.

- Before the Guitar, There Was the Ball

- The Philosophy of Play: Football as Bob’s First Religion

- The Footballer in the Musician

- The Trenchtown to Turf Bridge

- London, Adidas, and the Diaspora Football Culture

- Healing Through Football: A Body in Pain, a Spirit in Play

- The Global Symbol: Football and Reggae as Parallel Movements

- Bob Marley’s Football Legacy in Today’s World

- If Not Music, Then Football: The Hypothetical Destiny

- The Goal Beyond the Goalpost (Conclusion)

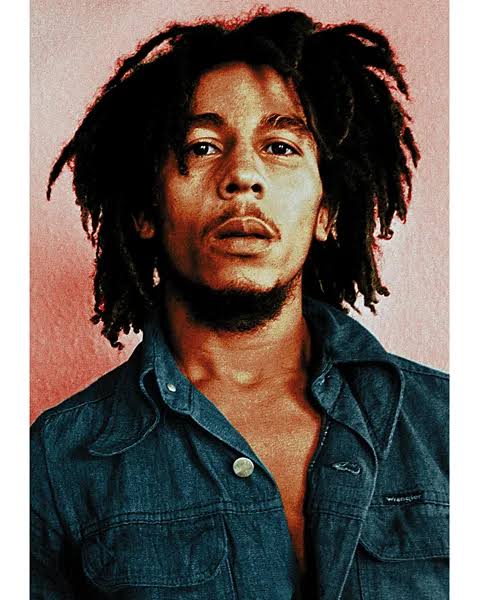

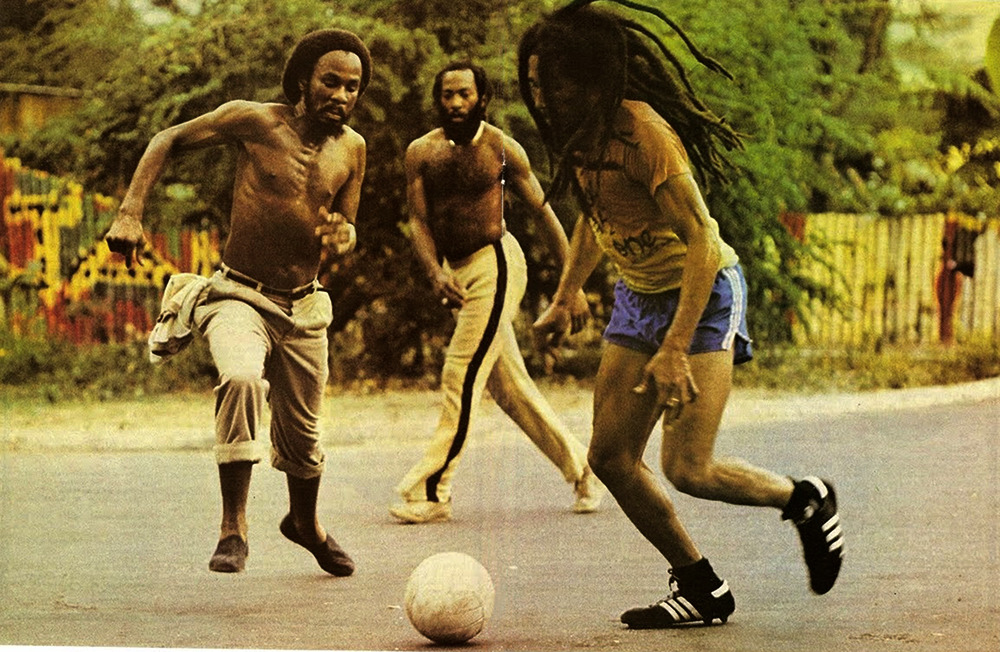

Imagine the scene: Trench Town, late 1950s. A boy with wiry limbs, eyes sharp with determination, mane yet to grow, runs barefoot through the dust. The ball is not leather, not stitched with precision, but scraps of cloth tied together into a makeshift globe. He dribbles past older boys, his rhythm deceptive, his movement quicksilver. No guitar hangs on his shoulders, no microphone stands in reach. Only the ball, the game, and the freedom it brings.

To the outside world, Marley’s destiny looks inevitable: reggae was his calling, Rastafari his vision, rebellion his platform. But to those who knew him intimately, football was the first language he spoke fluently, the passion that consumed him even more than rehearsals. His bandmates often joked that music was what Bob did for survival, but football was what he lived for.

It is tempting to believe that Marley’s greatness lay solely in his songs — that haunting cry of “Redemption Song”, the immortal “One Love”, the revolutionary “Get Up, Stand Up.” Yet beneath the global soundtrack he gave the world was the heartbeat of a player, not just a singer. His agility on stage owed itself to afternoons on the pitch. His philosophy of freedom echoed the improvisation of football. Even his tragedies, including the melanoma that began in a football injury, were bound to the game.

To fully grasp Bob Marley’s glorious destiny, one must look not just at the records he cut, but at the passes he made, the goals he chased, and the rhythm he first discovered not in song — but in football.

Before the Guitar, There Was the Ball

Every Jamaican child of Marley’s era knew that football was the kingdom of boys. In the post-colonial shadows of Kingston, where poverty pressed like a heavy sky, football fields were rare, but imagination wasn’t. Children kicked coconuts, tin cans, anything round enough to move. For young Robert Nesta Marley, born in 1945 in the rural parish of St. Ann and later raised in the raw energy of Trench Town, the ball became his earliest companion.

The streets themselves were Marley’s training ground. There were no jerseys, no referees, no nets — only dusty lots that transformed into battlegrounds when schoolboys decided to settle pride with skill. It was in this chaos that Bob discovered rhythm. His dribbling was sharp, unpredictable, carried on the syncopated timing that would later mark his music. He was not the biggest, nor the strongest, but he had vision — the ability to anticipate movement, to read a game unfolding.

What others heard in the bassline of reggae, Marley first felt in the pulse of football. Each kick was a beat, each sprint a phrase, each goal a chorus of release. Before he was a messenger of Rastafari, he was a boy who learned that joy could be created by shaping chaos into beauty, by turning dust into destiny.

The Philosophy of Play: Football as Bob’s First Religion

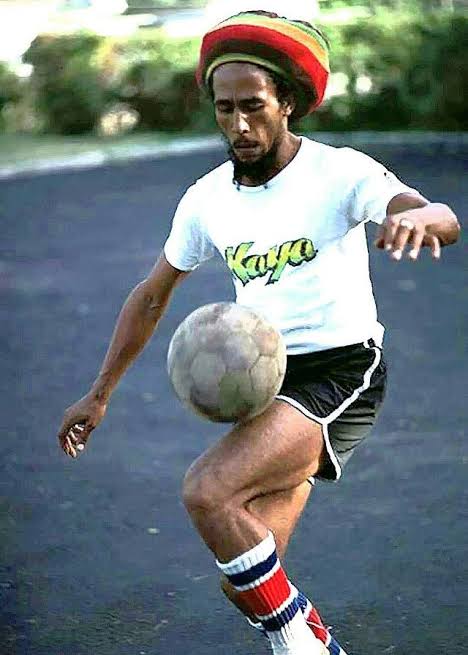

Bob Marley did not treat football as a pastime. For him, it was sacred — a daily ritual that gave his life structure. Where others smoked to pass time, Bob played. Where others argued politics, Bob organized matches. His friends recalled that no rehearsal could begin until a football game was played. In London, in Kingston, even backstage before shows, Marley would be seen lacing up his Adidas boots, ball at the ready.

He often said: “Football is freedom.” That simple declaration carried the weight of a philosophy. The field was democracy; every man equal before the ball, regardless of class or color. Football was rebellion; to play with joy in the face of hardship was to resist despair. And it was rhythm — the same rhythm he later harnessed in reggae.

When Marley spoke of life, he spoke as though it were a match. Attack and defense, improvisation and discipline, victory and loss. He was not the type to analyze formations or memorize tactics; his love was for the spontaneity of the game. To him, football was art — a canvas for expression, no different from a stage.

Even his spirituality flowed through the game. Rastafari preached unity, discipline, the pursuit of freedom. On the pitch, Bob embodied all three. Football was his meditation, his communion, his way of touching the divine without words.

The Footballer in the Musician

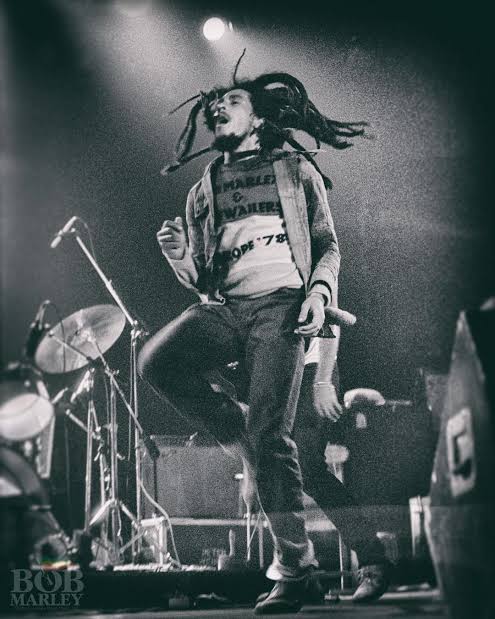

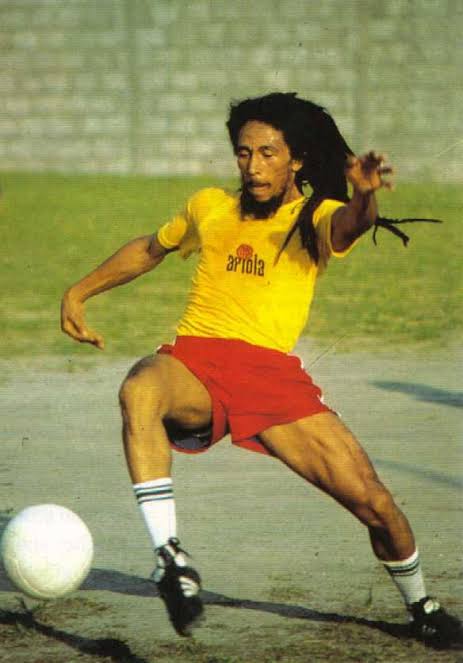

Watch Marley perform and you’ll see the player behind the prophet. His stage movements — the sudden sprints, the leaps, the pivots — were rehearsed not in dance studios, but on football fields. He ran with the same low center of gravity he used to dodge tackles. His energy seemed endless, his balance unshakable, as if every concert were a 90-minute match.

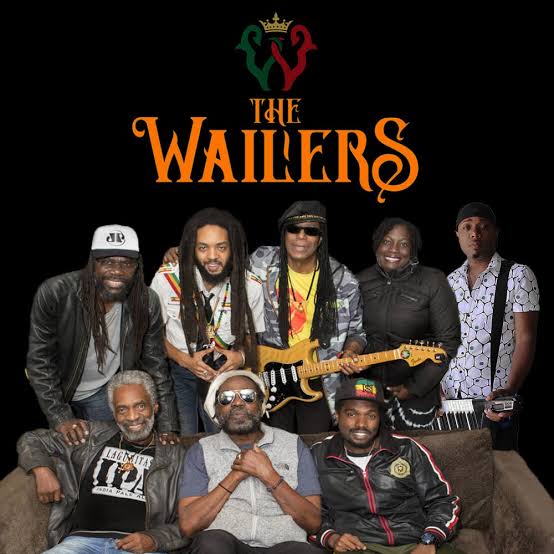

The Wailers themselves understood this. They weren’t just a band; they were a football team. Instruments in the evening, matches in the morning. Marley would challenge road crew, fans, even journalists to games, and often insisted that the day’s work wait until the ball had been played. The camaraderie of football — the reliance on teammates, the trust in collective movement — shaped how Marley led his band.

Some have said reggae was Marley’s dribble: weaving through oppression with syncopated steps, shifting directions unexpectedly, breaking open defenses with rhythm instead of brute force. Just as a striker sees space others don’t, Marley heard sounds others missed, threading notes into melodies that seemed inevitable only after he created them.

Football didn’t just influence his music. It gave it the body, the physicality, the forward motion that made Marley’s performances not just concerts, but battles — each song a strike toward freedom.

The Trenchtown to Turf Bridge

To fathom how football shaped Marley’s destiny, one must see Trench Town not just as a slum but as a proving ground. Football was more than recreation there; it was social currency. A boy’s reputation was sealed not by his grades in school, but by how well he dribbled, how many goals he scored, or whether he could hold his own against older players.

For Marley, who was of mixed heritage — the son of a white Jamaican father and a Black Jamaican mother — identity was always contested. He was teased for his lighter skin and sometimes treated as an outsider. Football was the first arena where those divisions dissolved. On the pitch, skill spoke louder than skin. A good pass earned respect, a brilliant goal silenced doubt.

This bridging power of football mirrored the role music would later play in his life. Both became ways for Marley to cross divides, to create belonging where there was separation. When he began forming friendships with other boys in Trench Town who were interested in music, it was often football that first bound them. Peter Tosh, Bunny Wailer, and other early collaborators knew Bob as much for his footwork as his voice. Football built trust, camaraderie, and discipline — the very foundations of what later became the Wailers.

The dusty lots of Kingston were thus not only Marley’s rehearsal studios for music, but his first classrooms in leadership. He learned when to pass and when to hold, when to lead the charge and when to trust a teammate. Football made him not just a better player, but a better bandmate, a better performer, and eventually, a better messenger for an entire generation.

London, Adidas, and the Diaspora Football Culture

When Marley moved between Jamaica and London during his career, he carried football like a passport. In Britain, the game was already more than sport — it was culture, identity, politics. For Caribbean immigrants in the 1970s, football fields in neighborhoods like Brixton were sanctuaries where they could assert pride and resilience in a society that often rejected them.

Marley’s passion for football became a bridge into these communities. He was not just a superstar in a recording studio; he was a man who would lace up Adidas boots and join a pick-up match on a London field. Fans who encountered him there remembered him not as a distant legend, but as a teammate, sweat-soaked and competitive, shouting for the ball like any other player.

The Adidas brand itself became tied to Marley’s image. Photographs of him juggling a ball in Adidas gear created an enduring association between reggae style and sportswear fashion. Decades later, Adidas still leans on Marley’s image to sell shoes and apparel, not simply because he was a musician, but because he embodied the athletic cool that made football and reggae global twins of youth culture.

Football also gave Marley kinship with African players and fans in Europe. For the African diaspora, both reggae and football were lifelines to identity. Marley’s presence on the field, his willingness to sweat beside everyday people, deepened his authenticity. He was not just preaching unity in lyrics; he was practicing it on the turf.

Healing Through Football: A Body in Pain, a Spirit in Play

Yet Marley’s love for the game was not without cost. The very passion that gave him joy also marked the beginning of his decline. In 1977, during a casual football game in Paris, Marley injured his big toe. The wound seemed minor, but doctors discovered it concealed a malignant melanoma.

To most men, the prescription would have been simple: amputation of the toe, removal of the cancer. But Marley’s Rastafarian beliefs forbade cutting the body. He refused. The cancer spread. The irony was bitter: the game that kept him grounded, the game that gave him balance and discipline, had opened the door to his greatest enemy.

And yet, even as the illness worsened, Marley would not give up football. Friends and bandmates remembered him playing matches when he should have been resting. To Bob, football was not negotiable — it was oxygen. Even as his body weakened, he craved the feeling of ball against foot, the rush of sprinting across grass, the strategy of attack and defense.

In this, football became his healer, not his killer. It gave him dignity when sickness stole his strength. It allowed him to remain not just Bob Marley the star, but Bob Marley the man — still competing, still laughing, still part of a team. If music was his message to the world, football was his therapy against despair.

The Global Symbol: Football and Reggae as Parallel Movements

By the late 1970s, Marley’s global stature had grown beyond music. He was no longer just Jamaica’s voice — he was Africa’s, the Caribbean’s, the oppressed world’s. In that same period, football too was emerging as the global stage for identity and politics. The World Cup was becoming a platform not only for sport but for nationhood, resistance, and pride.

It is no accident that Marley’s lyrics often paralleled football’s ethos. Reggae preached unity, football demanded teamwork. Reggae gave rhythm to the voiceless, football gave them victories to celebrate. Both transcended borders, languages, and governments.

The “One Love Peace Concert” in Kingston, 1978, where Marley famously joined the hands of political rivals Michael Manley and Edward Seaga, felt less like a concert and more like a symbolic football match. Two sides, divided by violence, brought into the same arena, called to play together for the sake of the crowd. Marley was not scoring goals, but he was refereeing history, blowing the whistle on division, and demanding the game go on in peace.

To millions across continents, Marley became the cultural equivalent of a football captain. He wasn’t just singing songs — he was leading humanity onto the field, reminding them of their shared rules, their shared victory.

Bob Marley’s Football Legacy in Today’s World

More than four decades after his passing in 1981, Bob Marley remains as present on football pitches as he does on concert playlists. Walk into a youth academy in Lagos, Accra, Kingston, or Rio, and you will likely hear his voice rising from a speaker by the sidelines. One Love is not just a song; it has become a halftime hymn, a reminder that the game unites beyond rivalries.

Professional footballers often carry Marley as an invisible captain. Didier Drogba, the Ivorian striker who helped bring peace to his war-torn nation, reflected Marley’s belief that sport could bridge politics. Raheem Sterling of England, born to Jamaican parents, grew up with Marley’s face and music as part of his cultural DNA. Neymar in Brazil, Pogba in France, countless African and Caribbean stars — they all trace lines of inspiration back to Marley, whose life insisted that artistry and athleticism were two halves of the same freedom.

Marley’s Adidas image has outlived even football eras. Photographs of him juggling a ball in sweatpants, hair flying, boots flashing, have become style bibles for streetwear. Brands reproduce his likeness not just to sell nostalgia, but because Marley continues to embody the essence of play: freedom, grit, joy.

In Jamaica itself, Marley’s love for football birthed a culture of musicians-as-athletes. Reggae Sunsplash festivals often opened with football tournaments. His sons — Ziggy, Stephen, Damian — inherited not only musical genius but the instinct to organize matches wherever they traveled. Football became Marley’s unspoken will to his children and his people: play the game, live the rhythm, keep moving forward.

If Not Music, Then Football: The Hypothetical Destiny

What if Bob Marley had chosen football instead of music? The thought is more than fantasy; it is rooted in truth. By his teenage years, Marley was already known in his neighborhood as a fierce player. He played winger, quick on the break, a master of surprise runs. Some believed that had opportunity allowed, Marley could have played in Jamaica’s National Premier League.

Imagine him, not with a guitar slung over his shoulder, but in a black, green, and gold jersey, leading Jamaica’s Reggae Boyz onto the field decades before they became a World Cup story. His charisma, his relentless energy, his refusal to back down — all were traits of a born captain.

And perhaps, had he pursued that path, his destiny would not have been so different. Football too would have made him a symbol of freedom, a figure larger than the game. He might not have sung Exodus, but he would have embodied it — carrying Jamaica out of obscurity into the world’s arenas.

Yet destiny is never so easily rewritten. Football gave him rhythm, discipline, philosophy — but music gave him immortality. Still, the hypothetical invites reflection: maybe Bob Marley was never a musician who loved football, but a footballer who discovered that his true pitch was the stage.

The Goal Beyond the Goalpost (Conclusion)

Bob Marley’s life was cut short at 36, his voice stilled by illness, his body carried back to Nine Mile in St. Ann Parish. But his story refuses silence. He is heard in chants on terraces, in locker room playlists, in the joy of boys playing barefoot on Jamaican sand or Nigerian streets.

To call Marley merely a musician is to miss half his heartbeat. Football was the compass that guided his steps, the rhythm that taught him how to move, the community that showed him how to lead. Without football, there may have been no Marley as the world knows him. His stagecraft, his spiritual philosophy, his insistence on unity — all bore the fingerprints of the game.

In the end, Bob Marley did not separate the two. Football and music were twin halves of one spirit, each feeding the other. Where football gave him movement, music gave him meaning. Where football gave him camaraderie, music gave him congregation. Where football gave him play, music gave him prophecy.

Even in death, football remained with him: a ball is said to be buried alongside his body in Nine Mile, a silent testament to the game that shaped his destiny.

His destiny was glorious not because he chose music over football, but because he allowed football to shape the music. And so the boy from Trench Town who first found freedom chasing a tattered ball gave the world freedom in song. His life was a match without boundaries, and when the final whistle blew, the world rose not in mourning, but in applause.