The night air in Oyo still carries a weight that words cannot quite capture. Travelers who have walked the silent courtyards of the old Alaafin’s palace speak of a stillness so profound that even the bats seem to hesitate before cutting across the dusk. There is no visible storm, yet the sky feels heavy, charged, as though thunder itself is crouched behind the clouds waiting for the smallest provocation.

In those moments, one can almost hear the echo of an ancient warning—an admonition carried through generations: there are some stories too sacred to summon carelessly, and some names that demand more than mere performance.

When filmmakers in the late twentieth century set their eyes on dramatizing the life of Sango—the fiery Alaafin of Oyo who was both king and later deified as Orisha of thunder and lightning—they were not simply attempting to retell history. They were stepping into territory that chiefs, priests, and custodians of Yoruba tradition had long considered perilous. For to stage Sango was not merely to recreate a monarch’s reign; it was to conjure forces that Yoruba cosmology insists remain alive, breathing, and watchful.

It was in this tense intersection—between art and taboo, ambition and reverence—that Yoruba chiefs voiced their sternest warning: filming Sango without the blessings of the tradition was not just risky—it was cursed.

This is not a tale of superstition alone. It is the story of how history, cinema, and cultural guardianship collided under the heavy skies of Yoruba land; how chiefs, bound by duty to ancestral codes, resisted what they saw as sacrilege; and how Nollywood itself was forced to reckon with questions of authenticity, reverence, and danger.

The King Who Became Thunder

Long before the cameras of Nollywood rolled, Sango was already immortal. He was no ordinary monarch but the third Alaafin of Oyo, a man whose reign was marked by fierce military campaigns, complex political rivalries, and ultimately, tragedy that transformed into myth.

Historically, Sango is remembered as a powerful warrior who wielded both fear and charisma. He was said to control storms, commanding lightning as both weapon and spectacle. Oral tradition tells of his volatile temper and how his enemies conspired against him until he took his own life—or, as the more spiritual versions maintain, until he vanished into the earth at Koso and became divine.

Unlike other rulers whose deaths closed their chapters, Sango’s departure opened an entirely new one. He was not buried and forgotten; he was reborn as Ṣàngó, the Orisha of thunder, worshipped in shrines across Yorubaland and beyond.

His cult spread with the Yoruba diaspora, finding new expressions in Brazil (as Xangô), Cuba (as Changó), and Trinidad (as Shango). But in Yorubaland itself, Sango remained both royal ancestor and god, a dual identity that placed his story in a delicate zone of respect. Chiefs who swore oaths of allegiance to the Alaafin carried his memory as sacred. Priests tended his shrines with ritual precision. To trivialize his story was to risk provoking not just cultural outrage but divine retaliation.

Taboos, Chiefs, and the Weight of Èèwọ̀

In Yoruba culture, èèwọ̀ (taboo) is not superstition—it is structure. It is the invisible scaffolding that holds society together, defining what may be spoken, what may be done, and what must never be dared. To cross èèwọ̀ is not merely to break a rule but to unbalance the harmony between humans, ancestors, and the Orisha.

Chiefs like Sangodele Atanda, the Elegun Sango of Oyo Kingdom, as custodians of this order, take their role as guardians of taboo with the utmost seriousness. In the context of Sango, their caution was sharpened by several factors:

Royal Ancestry: Sango was no distant myth. He was a king whose descendants and spiritual heirs still sit in council. His story remains woven into the fabric of living royal identity.

Ritual Power: His worship is not extinct. Thunderstones, shrines, and annual festivals keep his presence alive in Yoruba consciousness.

Cultural Ownership: Chiefs saw themselves as protectors of sacred heritage. Allowing outsiders—or even Nollywood itself—to distort Sango’s memory would dishonor not just the past but the gods themselves.

Thus, when the idea of a film about Sango surfaced, it was not met with excitement alone. It was also met with fear. Chiefs gathered in hushed meetings, warning producers that certain lines must not be crossed. Sango’s life, they cautioned, was not stagecraft. It was fire.

The language of their warnings was not ambiguous. Some spoke of misfortune—equipment failing, accidents on set, finances mysteriously drying up. Others invoked stronger imagery: that any reckless summoning of Sango’s likeness without ritual appeasement would invite thunder itself.

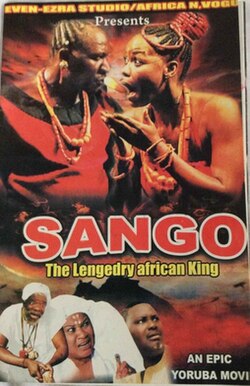

Nollywood’s First Attempt — Sango: The Legendary African King (1997)

Before the controversy of Klaus Stephan’s 2006 Sango, there was Obafemi Lasode’s groundbreaking 1997 film, Sango: The Legendary African King. Considered one of the most ambitious Nigerian epics of its time, the film dramatized the life, reign, and deification of the Alaafin of Oyo who became the Orisha of thunder.

Lasode’s Sango stood out for several reasons:

Scale and Production: With elaborate costumes, large battle sequences, and a cast filled with Yoruba theatre veterans, it set a new benchmark for Nollywood’s handling of historical epics.

Cultural Anchoring: Unlike later foreign-led interpretations, Lasode’s work leaned heavily on Yoruba oral tradition and dramatization styles, echoing earlier stage productions by Duro Ladipo and others.

Controversy and Reverence: Even at its release, whispers circulated about whether such a sacred story should be committed to film at all. Chiefs and cultural custodians worried that depicting Sango visually could provoke ancestral displeasure.

Despite these concerns, the film received acclaim for attempting to place Yoruba history and cosmology on the cinematic map, positioning Sango not only as a local hero but as a pan-African cultural symbol.

But the debates it ignited—about reverence, authenticity, and taboo—laid the groundwork for the much fiercer backlash that greeted Klaus Stephan’s 2006 Sango. Where Lasode’s film was seen as bold but respectful, Stephan’s was criticized as culturally alien and dangerously careless with sacred material.

This controversy sharpened an already simmering question: Can sacred Nigerian myths survive the translation to film without losing authenticity? The chiefs’ earlier warnings about curses, misfortune, and taboo violations now seemed less like superstition and more like cultural foresight. They feared that careless adaptations would not only distort Sango’s story but also weaken the authority of Yoruba custodianship in an era when global cinema was eager to mine Africa for epic narratives.

Global Echoes of Sango

Ironically, while chiefs in Nigeria warned against dramatization, Sango’s legend was thriving abroad.

In Brazil, Sango (as Xangô) was celebrated in music, carnival, and Candomblé rituals. In Cuba, Changó became one of the most popular Orishas, embodying masculinity, rhythm, and fire. Across the Caribbean, Shango cults flourished, blending Yoruba cosmology with local traditions.

This global embrace highlighted a paradox. While Yoruba chiefs insisted on sacred caution, the diaspora had turned Sango into both spiritual icon and cultural symbol. Yet even abroad, rituals of respect remained. Xangô was not casually performed; he was invoked with offerings, drumming, and ritual choreography.

This global resonance only deepened the chiefs’ conviction: if even distant communities preserved reverence, why should Nollywood treat Sango as mere content?

Between Faith and Film

The debate over filming Sango became a mirror of larger questions in Nigeria: How should modernity engage tradition? Can sacred heritage be commodified without losing its power? What is the responsibility of filmmakers when dealing with histories still alive in spiritual consciousness?

For chiefs, the answer was clear. Their warnings were not censorship but guardianship. They saw themselves as keepers of fire, preventing careless hands from being burned.

For filmmakers, however, the challenge was artistic. To tell Nigeria’s grandest stories, they had to wrestle with taboos. They had to find a path between respect and creativity. Some sought compromise—consulting priests, offering rituals before filming. Others chose avoidance, leaving Sango’s story untouched, as though the thunder god had placed himself beyond cinema’s reach.

Conclusion: Thunder That Never Dies

The warnings of Yoruba chiefs were never idle threats. They were cultural codes, ancestral laws, reminders that some stories are not simply told—they are invoked. In guarding Sango’s legacy, chiefs were not suppressing creativity but upholding a principle: that heritage demands reverence, and that the past lives on in forms modernity cannot always control.

To this day, the notion of a “royal curse” lingers in Nollywood memory, not as superstition but as a parable. It reminds us that art is powerful, that stories can stir forces beyond the screen, and that the line between history and divinity is thinner than it appears.

In Yorubaland, thunder still rolls across the skies with a majesty that silences conversation. And when it does, one cannot help but think of Sango—not as myth, not as character, but as living force.

Perhaps this is why chiefs warned against filming him. For some legacies are not meant to be contained in reels and scripts. They are meant to rumble eternally, like thunder itself, across the memory of a people.

![Cubana protecting our interest — Amakaeze siblings disown brother’s claims on disputed Abuja property [VIDEO]](https://keeploss.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/cubana-protecting-our-interest-amakaeze-siblings-disown-brothers-claims-on-disputed-abuja-property-video-150x150.jpg)